Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 16 January 2013

A Y-like social chromosome causes alternative colony organization in fire ants

J. Wang, Y. Wurm, M. Nipitwattanaphon, O. Riba-Grognuz, Y. Huang, D. Shoemaker, L. Keller

Nature, 2013, 493:664-8

Abstract

Intraspecific variability in social organization is common, yet the underlying causes are rarely known1,2,3. In the fire ant Solenopsis invicta, the existence of two divergent forms of social organization is under the control of a single Mendelian genomic element marked by two variants of an odorant-binding protein gene4,5,6,7,8. Here we characterize the genomic region responsible for this important social polymorphism, and show that it is part of a pair of heteromorphic chromosomes that have many of the key properties of sex chromosomes. The two variants, hereafter referred to as the social B and social b (SB and Sb) chromosomes, are characterized by a large region of approximately 13 megabases (55% of the chromosome) in which recombination is completely suppressed between SB and Sb. Recombination seems to occur normally between the SB chromosomes but not between Sb chromosomes because Sb/Sb individuals are non-viable. Genomic comparisons revealed limited differentiation between SB and Sb, and the vast majority of the 616 genes identified in the non-recombining region are present in the two variants. The lack of recombination over more than half of the two heteromorphic social chromosomes can be explained by at least one large inversion of around 9 megabases, and this absence of recombination has led to the accumulation of deleterious mutations, including repetitive elements in the non-recombining region of Sb compared with the homologous region of SB. Importantly, most of the genes with demonstrated expression differences between individuals of the two social forms reside in the non-recombining region. These findings highlight how genomic rearrangements can maintain divergent adaptive social phenotypes involving many genes acting together by locally limiting recombination.

The fire ant S. invicta is characterized by a remarkable form of social polymorphism under the control of a single Mendelian factor4–6,8. Remarkably, a genomic element marked by the gene Gp-9 determines whether workers tolerate a single fertile queen (monogyne social form) or several fertile queens (polygyne social form) in their colony. Colonies containing only homozygous Gp-9BB workers accept only a single Gp-9BB queen, whereas colonies containing both Gp-9BB and Gp-9Bb workers will invariably accept several queens, but only Gp-9Bb queens7,8. The monogyne and polygyne social forms differ in numerous important aspects of their biology, including the level of aggression between colonies and how new colonies are initiated9. These important behavioural differences are associated with a suite of morphological and life-history differences among individuals with alternative Gp-9 genotypes, including queen fecundity, their tendency to accumulate fat during sexual maturation, the odour of mature queens, the number of sperm produced by males, and the size of workers4–7,10–12.

The fact that Gp-9 codes for an odorant-binding protein (OBP), coupled with evidence that selection acted to drive the molecular divergence of Gp-9b alleles from the ancestral Gp-9B allele, has led to the suggestion that this gene may have a direct role in regulating social organization by means of chemical communication7,13. However, because it is unlikely that an OBP also affects traits as diverse as female size, female fecundity and male spermatogenesis, it has been suggested that Gp-9 might be part of a supergene comprising many genes in tight linkage10,12,14. The existence of such clusters of loci facilitating the co-segregation of adaptive variation has been demonstrated in some classical cases of floral types (for example, ref. 15) and insect mimicry (for example, see refs 16, 17), but it remains an open question whether a polymorphic supergene is responsible for controlling the important phenotypic differences and the large suite of traits associated with variation in social organization of S. invicta colonies.

We used restriction-site-associated DNA (RAD) tag sequencing18 to investigate whether Gp-9 is located within a region with reduced recombination (supergene). In a first experiment, we obtained a total of 121 million RAD tag sequences from 95 Gp-9B haploid sons of a Gp9BB monogyne queen (M013, Supplementary Table 1). We retained 4,983 high-coverage biallelic RAD markers from 87 informative males passing our filtering criteria to generate a genetic linkage map. The results, together with those from two other independent monogyne families, revealed 16 main linkage groups (Supplementary Figs 1–3) corresponding to the 16 chromosomes of S. invicta19.

In a second experiment, we generated 92 million RAD tag sequences from 110 haploid sons of a Gp-9Bb polygyne queen (P034, Supplementary Table 1). Ninety-two informative males (45 Gp-9B and 47 Gp-9b) were used to construct a genetic linkage map comprising 2,796 biallelic RAD markers. Fifteen of the sixteen linkage groups in this new map were largely co-linear to those identified for the genetic maps above based on common RAD markers and their associated physical scaffolds. However, the linkage group containing Gp-9 differed markedly between the two experiments, with 285 (10.2%) markers exhibiting no recombination with Gp-9 in the sons of the Gp-9Bb queen (Supplementary Fig. 4). This non-recombining region corresponds to approximately 13.8 megabases (Mb) of the estimated 23 Mb assembled linkage group of this chromosome based on the sizes of the physical scaffolds identified by the genetic markers for this family and the three monogyne families.

Further RAD sequencing (RADseq) data from the male offspring of three Gp-9Bb polygyne queens (n = 31 (P008), 46 (P016) and 46 (P033) sons; Supplementary Figs 5–7 and Supplementary Table 1) confirmed that the non-recombining supergene marked by Gp-9b is a general characteristic of S. invicta, with a complete absence of recombination over 13.2% (478 out of 3,614), 12.1% (160 out of 1,380) and 11.0% (812 out of 7,360) of the markers assayed in the respective three families. There was very strong overlap among the non-recombining scaffolds in the Gp-9-linked region of family P034 and these three families (P008, 31 out of 31; P016, 19 out of 21; P033, 41 out of 41). Overall, the estimated size of the non-recombining region is 12.7 Mb based on the combined data of these four polygyne families (Fig. 1a), and includes at least 616 (3.7%) of the 16,522 known S. invicta genes20.

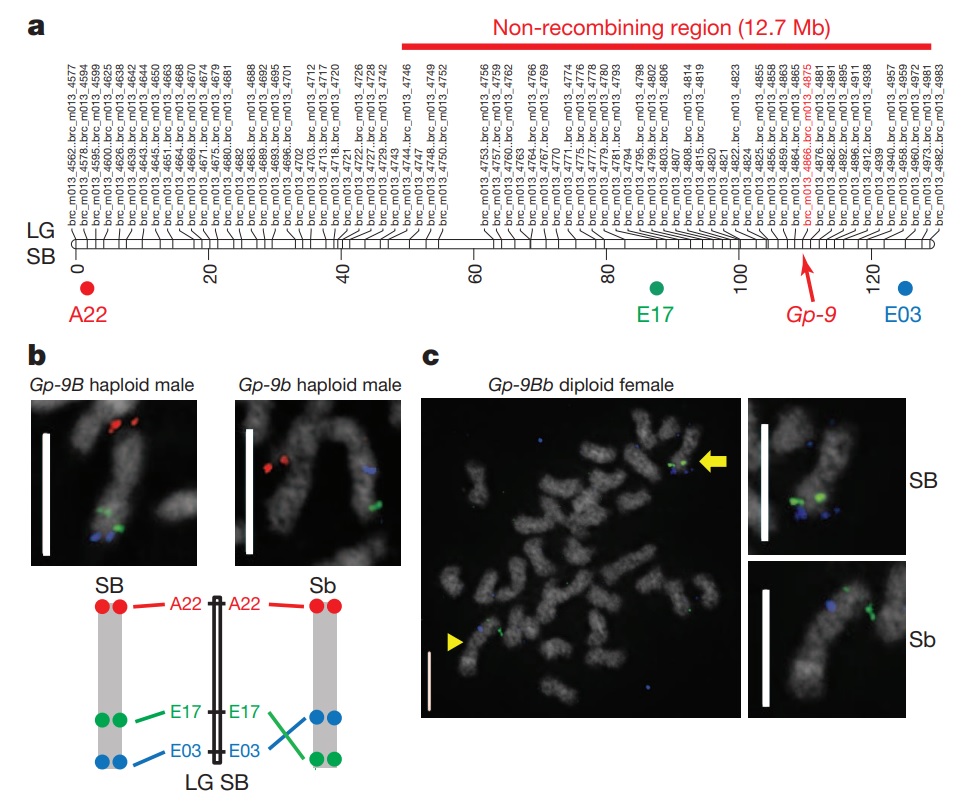

Figure 1 – Fine-scale mapping and BAC-FISH analysis of the social chromosome.

a, Fine-scale linkage map of the SB social chromosome derived from RADseq analysis of male offspring from a monogyne Gp-9BB queen (M013). Genetic positions in centimorgans (below) and RAD marker names (above) are indicated. Each genetic marker has a prefix (brc_m013_) and a number based on its serial position on the map. Multiple markers that have the same map position are indicated using ‘first…last’ marker notation. The positions of Gp-9, BAC probes and the extent of the non-recombining region in Gp-9Bb queens are indicated. Genetic maps for all seven families are in Supplementary Figs 1–7 and precise genetic and physical positions of genetic markers are in Supplementary Tables 8–14. LG, linkage group. b, BAC-FISH identifies an inversion between the SB and Sb social chromosomes. Social chromosomes from a Gp-9B haploid male (SB chromosome, left) and Gp-9b haploid male (Sb chromosome, right). The bottom panel shows a schematic interpretation of hybridization patterns as well as BAC positions on the SB genetic map. Images with all chromosomes of the respective cells are in Supplementary Fig. 8. c, BAC-FISH on full chromosome complement from one cell of a diploid Gp-9Bb female (SB/Sb chromosomes). Both orientations corresponding to SB (arrow) and Sb (arrowhead) can be observed. Magnified views of respective social chromosomes are on right. Chromosomes are counterstained with 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; white) and hybridized with fluorescently labelled BAC probes: A22 (red, b), E17 (green, b, c) and E03 (blue, b, c). Scale bars, 5 μm.

This number is probably an underestimate because only 82% (13,557 out of 16,522) of the genes have been assigned a genetic map position. Importantly, there was no evidence of reduced recombination in this 12.7-Mb region in the three monogyne families headed by Gp-9BB queens (two-factor mixed-model analysis of variance (ANOVA) on log recombination rate, F1,44 = 0.17, P = 0.68).

The suppressed recombination near Gp-9 was further confirmed by examining insertion-deletion (indel) alleles in four Gp-9B and four Gp-9b males from each of five further independent polygyne families. We sequenced and performed a de novo assembly of the genome of a Gp-9b male as previously done for the Gp-9B genome to identify indel polymorphisms in the Gp-9-linked region and also to permit detailed sequence comparisons (below) between the Gp-9B and Gp-9b alleles in the non-recombining supergene20. Indel-specific PCR assays for 16 randomly selected Gp-9-linked loci confirmed a complete lack of recombination between the two Gp-9-linked regions (Supplementary Table 2). Having established that the B and b variants of this linkage group are a general characteristic of S. invicta, we hereafter refer to them as social B and social b (SB and Sb) chromosomes.

Chromosomal rearrangements are a key mechanism preventing recombination between homologous chromosomes17,21. We performed bacterial artificial chromosome fluorescent in situ hybridization (BAC-FISH) to test whether an inversion between SB and Sb could contribute to reduced recombination. Multicolour BAC-FISH on Gp9B haploid males revealed a BAC hybridization pattern concordant with the SB genetic map in the five individuals analysed (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Figs 8 and 9a–d), whereas all six Gp-9b haploid males analysed exhibited an inverted BAC hybridization pattern for the probes in the non-recombining region (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Figs 8 and 9a–d). Both orientations were observed in the three Gp-9Bb diploid females analysed (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 9e). These data demonstrate the presence of a large inversion, which, on the basis of the map positions of the BACs tested, is at least 9.3 Mb.

In addition to this large chromosomal inversion, sequence comparisons between SB and Sb revealed a smaller 48 kilobase (kb) inversion in the non-recombining region (Supplementary Fig. 10). Intriguingly, this inversion is adjacent to a 3-kb transposed sequence that interrupts SI2.2.0_02248, a putative acyl-CoA desaturase. Genes in this family have a role in pheromone and cuticular hydrocarbon synthesis22, raising the possibility that this rearrangement could be involved in odour differences existing between Gp-9BB and Gp-9Bb queens, which are the cues known to be used by workers to discriminate between queens of alternative genotypes7. High-throughput RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) comparisons did show that this gene was expressed at a significantly lower level in Gp-9b males (2.9 reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads (RPKM)) than in Gp-9B males (10.7 RPKM; likelihood ratio test on negative binomial generalized linear model P = 0.001). Moreover, the analysis of males from the five additional families above confirmed that this rearrangement is a general characteristic of the SB and Sb chromosomes (all 20 Gp-9B males had PCR product sizes specific to SB, whereas all 20 Gp-9b males had PCR product sizes specific to Sb; Supplementary Table 2). Thus, this rearrangement constitutes a general difference between the SB and Sb chromosomes and may be directly involved in odour differences between Gp-9BB and Gp-9Bb queens.

The selective pressures acting on the two heteromorphic social chromosomes identified in S. invicta should be similar to those acting on sex chromosomes and other genomic regions experiencing epistatic selection for reduced recombination23. Y chromosomes are generally thought to have evolved from an autosome after suppression of recombination between a ‘sex locus’, which makes bearers more likely to develop into a male than a female, and a nearby gene with sexually antagonistic alleles. Over evolutionary time, cessation of recombination occurs between the X and Y chromosomes, allowing additional genes beneficial for males but harmful to females to accumulate on the Y chromosome21,24. Analogous to the Y chromosome, which is only found in males (or theW chromosome in females), the Sb chromosome only occurs in one of the two alternative social forms (the polygyne form) of S. invicta. Colony queen number was likely to be a plastic and non-genetic ancestral trait in fire ants, as is probably the case in many other ant species1,9. Thus, in a similar manner to Y chromosome evolution, genes conferring both a higher fitness in polygyne colonies and a higher probability of queens of joining such colonies should be selected to become linked in a non-recombining region.

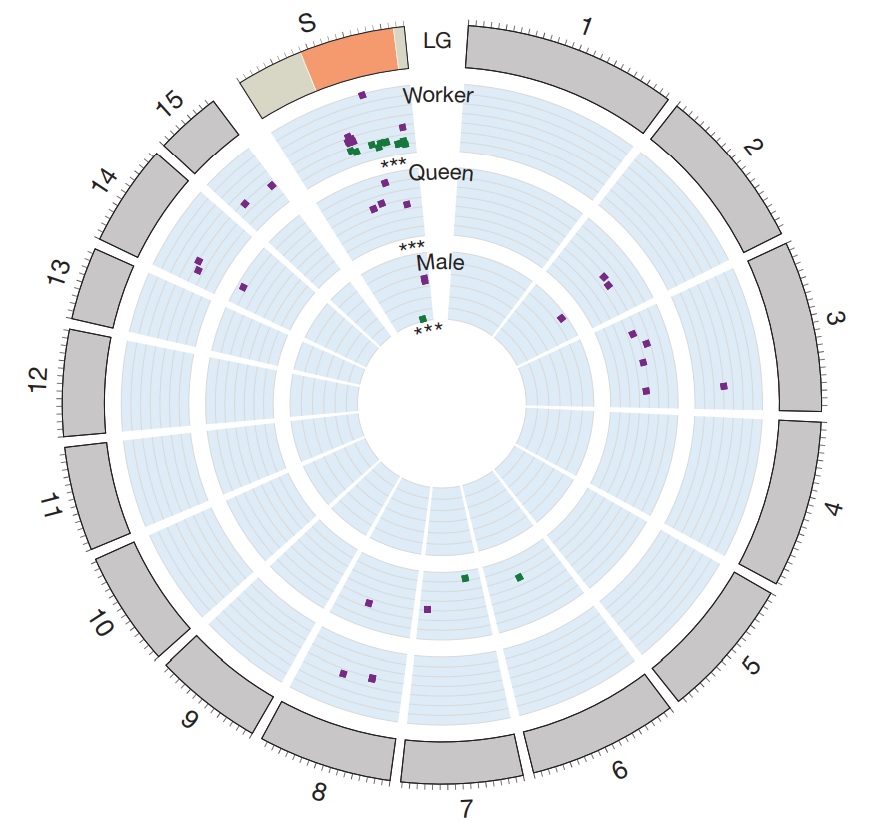

Importantly, the available data suggest that most phenotypic differences between individuals of the two social forms are directly associated with differences between the non-recombining regions of the SB and Sb chromosomes. Nineteen of the 27 (70%) genes previously shown to be differentially expressed between Gp-9BB and Gp-9Bb workers25 that could be mapped to linkage groups were in the nonrecombining region (Fig. 2), although this region only includes 4.9% of the 7,282 genes on the microarray with a genetic map position (hypergeometric test, P < 10–22). Microarray experiments revealed similar results for genes differentially expressed between queens and males of alternative Gp-9 genotype. Of the 38 genes differentially expressed between 1-day-old virgin queens with genotypes Gp-9BB and Gp-9Bb, 15 could be mapped to known linkage groups, four (27%) of which were located in the non-recombining region (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3; hypergeometric test, P < 0.0008). Similarly, of the five genes that were differentially expressed between Gp-9B and Gp-9b male pupae, four could be mapped to known linkage groups, three (75%) of which were located in the non-recombining region (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 3; hypergeometric test, P < 0.00012). Finally, 15 of the 616 genes in the non-recombining regions had dN/dS values (that is, the ratio of the number of non-synonymous substitutions per non-synonymous site to synonymous substitutions per synonymous site) significantly greater than one (Supplementary Table 4). High dN/dS values may be expected under adaptive or relaxed purifying selection. Six of the eight genes for which expression data are available exhibited a male-biased expression pattern (Supplementary Table 4), suggesting that they are functional and exposed to selection in males. Thus, the high dN/dS values of some genes may reflect adaptive evolution26 driving phenotypic differences between individuals of the two social forms.

Figure 2 – Expression of genes associated with Gp-9 genotype are overrepresented on the social chromosome.

The outer circle depicts the S. invicta chromosome ideograms. The social chromosome (S) is subdivided into the non-recombining (orange) and recombining (tan) regions. Genes differentially expressed between individuals of alternative Gp-9 genotypes in mature adult workers25, young adult queens and male pupae are plotted as squares according to their genomic location. The relative expression level (log2- transformed) of Gp-9BB to Gp-9Bb (worker and queens) or Gp-9B to Gp-9b (male) is also indicated, with squares closer to the circle centre having greater expression in Gp-9BB or Gp-9B individuals. Colours highlight direction of gene expression: green, expression in Gp-9BB (or Gp-9B) > Gp-9Bb (or Gp-9b); and purple, reversed. ***P < 0.001, hypergeometric test

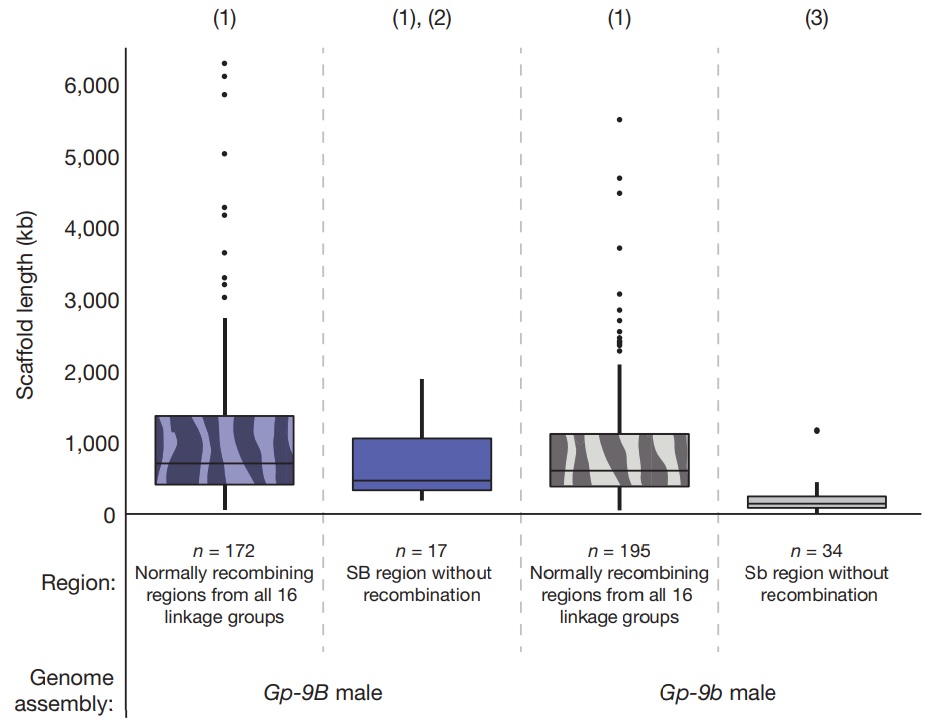

Another similarity between the Sb chromosome and the Y (or W) sex chromosome is that Sb contains one or more (recessive-lethal) deleterious mutations. Similar to Y chromosomes and supergenes in which there has been selection for suppressed recombination, the nonrecombining region of Sb is expected to experience less efficient purifying selection, and thus increased accumulation of mildly deleterious mutations. The non-viability of Sb/Sb individuals is one clear example and effectively prevents recombination in the 12.7-Mb region. Such non-recombining regions also feature higher frequencies of repetitive elements, longer introns and increased fixation of non-synonymous substitutions21,23,24,27. Consistent with these predictions, whole-genome sequence analysis of one Gp-9B son and one Gp-9b son from each of seven unrelated Gp-9Bb queens revealed that 17% (237 out of 1,461) of the known fire ant repetitive elements were significantly more frequent in Gp-9b than Gp-9B males, whereas only 0.7% (9 out of 1,461) were more frequent in Gp-9B males (false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected two-sided paired t-tests on numbers of reads matching each repetitive element; Supplementary Table 5). Also, scaffolds in the nonrecombining region of Sb were 2.7 times shorter than those of SB, and 3.3 times shorter than scaffolds from the rest of the Gp-9b assembly (Fig. 3), consistent with the prediction that higher frequency of repetitive elements in the non-recombining Sb region results in increased difficulties in assembly of this region. We also found that 49 out of 472 (10.4%) of the intron-containing protein-coding genes present in both genome assemblies had an intron at least 500 base pairs (bp) larger in the non-recombining region of Sb than SB (Fisher’s exact test, P < 10–10). Finally, the dN/dS ratios for genes in the non-recombining region of the social chromosome were significantly higher (0.21 ± 0.31, median ± standard error) than those for the remainder of the genome (0.12 ± 0.01; two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test, P < 10–4).

Although the above analyses reveal notable similarities among the Sb, Y and W animal chromosomes, we predict that the rate of gene degeneration in the non-recombining Sb region compared with Y and W animal chromosomes should be relatively slow because of purifying selection acting on genes expressed in ant haploid males. A similar argument has been made for algae and bryophytes, in which sex is determined during the haploid phase of the life cycle. Generally, individuals with the U chromosome develop as females and those with the V chromosome as males. The U and V chromosomes are predicted to be partly sheltered from genetic deterioration because they are subject to purifying selection as haploids21. Similarly, many genes in plants are also expressed in the haploid male gametophyte and are thus under strong selection owing to competition between the X- and Y-bearing pollen during pollination28. By contrast, haploid Y-bearing spermatozoa in animals show very limited gene expression, which probably accounts for the higher rate of degeneration of Y-linked genes in animals than in plants24.

Several lines of evidence suggest that purifying selection acting in haploid males may slow down degeneration of the non-recombining region of Sb. First, RNA-seq data revealed that the vast majority of S. invicta genes expressed in females are also expressed in haploid males (data not shown). Second, microarray experiments between Gp-9B and Gp-9b males revealed no differentially expressed genes in adults and only five differentially expressed genes in pupae (Supplementary Table 3). Third, 99.8% of the non-gap sequences alignable between the non-recombining regions of SB and Sb were identical and largely contained the same genes. Indeed, we identified missing exons in Sb compared with SB for only five out of 616 genes (Supplementary Table 6). Finally, the sequencing of six RNA pools, each of which comprised four Gp-9Bb queens contributing equal quantities of RNA, showed significant allele-specific expression differences for only 10.8% (31 out of 288, Supplementary Table 7) of the genes possessing single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the non-recombining region and no evidence of systematically higher expression of alleles on SB compared with those on Sb (binomial test, P = 0.11, Supplementary Fig. 11). This result contrasts with Drosophila miranda neo-sex chromosomes in which 80% of the genes on the neo-X chromosome have higher expression than those on the neo-Y chromosome29. Overall, these combined results suggest that the nonrecombining region of Sb has retained the vast majority of the genes and that purifying selection has acted as a potent force to slow down their rate of degeneration.

Figure 3 – Scaffolds lengths of the non-recombining region of the social chromosome (solid) and the rest of the genome (patterned) based on the genome assemblies of a Gp-9B (blue) and a Gp-9b (grey) male.

Box-andwhisker plots of scaffold lengths: the top and bottom of the box are the first and third quartiles, respectively; the horizontal bar within the box is median; whiskers extend from the box to the most extreme scaffold length within 1.5× of the interquartile range of the box; data beyond the whiskers are outliers and plotted as points. Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) comparisons among groups marked (1) are non-significant (P > 0.05), the comparison between (1) and (3) is significant (P < 10–7 ), and the comparison between (2) and (3) is also significant (P < 10–4).

The timing of the origin of the heteromorphic social chromosomes in fire ants is difficult to determine at present. A previous phylogenetic analysis of Gp-9 sequences from 21 fire ant (Solenopsis) species, of which four (including S. invicta) are socially polymorphic, revealed a perfect association between queen Gp-9 genotype and colony social form13. Specifically, in all the three other socially polymorphic species, all monogyne queens were homozygous for a Gp-9B-like allele similar to the Gp-9B allele found in S. invicta, whereas all polygyne queens had one copy of a Gp-9b-like allele, which again was very similar to the Gp9b allele identified in S. invicta. Importantly, these analyses showed that all Gp-9b-like alleles form a monophyletic group within the B-like alleles, consistent with a single origin of polygyny in this group. If Gp-9 in these three closely related species is also part of a supergene as we suspect, then recombination suppression between SB and Sb may be ancestral to speciation. Comparisons of the frequency of synonymous substitutions between SB and Sb alleles and the frequency of synonymous substitutions between genes of two leafcutter ants that diverged ~ 10 million years ago30 suggest that recombination suppression in the social chromosome occurred ~ 390,000 years ago (Supplementary Fig. 12 and Supplementary Information), which could be less than the divergence time (K. G. Ross, unpublished data) between these four socially polymorphic Solenopsis species. A more precise estimate of the divergence time of SB and Sb relative to the four species is required to test whether the divergence of SB and Sb predates speciation or whether introgression of Sb across species boundaries has occurred.

In conclusion, our study shows that colony social organization in the fire ant S. invicta is under the control of a pair of heteromorphic social chromosomes having many of the properties of sex chromosomes. The Sb chromosome only occurs in one type of social organization, which sets the stage for a specific selection regime very similar to that acting on sex-specific Y and W chromosomes. Indeed, the Sb chromosome has many similar properties to Y and W chromosomes, including a large non-recombining region, inversions, an increased amount of repetitive elements and deleterious mutations resulting in Sb/Sb individuals being non-viable. This is the first description of a social chromosome, yet it is likely that such supergenes affecting social organization also exist in other social insects. Polymorphism in social organization has evolved independently numerous times in ants where many species have both monogyne and polygyne colonies. The occurrence of the polygyne social form is associated almost invariably with a ‘polygyny syndrome’ in which, as in S. invicta, polygyne queens are smaller, accumulate less fat during sexual maturation, have lower fecundity and initiate new colonies with the help of workers rather than independently1,2. It will be interesting to investigate whether these differences, as in S. invicta, also result from genomic rearrangements creating a supergene containing many genes, which jointly provide integrated control to maintain divergent and adaptive social phenotypes.

Methods Summary

RADseq was performed on bar-coded male offspring from monogyne and polygyne families. Individual-specific data subsets were generated from the raw sequences and then deposited into family-specific MySQL databases using the FASTX-toolkit and Perl scripts. Loci that were biallelic in a family and monoallelic (that is, never heterozygous because ant males are haploid) in individual males were used to create family-specific genetic maps. Multicolour BAC-FISH was performed on chromosome preparations from imaginal discs using social chromosome-specific clones. The newly assembled Gp-9b genome was compared to the Gp-9B reference assembly using Ruby scripts and bioinformatics tools. The dN/dS ratios were calculated using codeml in PAML. Microarray-based gene expression differences were assayed using custom complementary DNA microarrays and analysed using limma (Bioconductor, R). The genetic positions of differentially expressed genes were determined by blastn comparisons of the microarray cDNAs to the genetically mapped physical scaffolds. SNPs were identified by sequencing several Gp-9B and Gp-9b individuals and by RNA-seq. Allele-specific expression was assessed by RNA-seq. Complete methods and further analyses are provided in the Supplementary Information

References

-

Bourke, A. & Franks, N. Social Evolution in Ants (Princeton University Press, 1995)

-

Keller, L. Social life – the paradox of multiple-queen colonies. Trends Ecol. Evol. 10, 355–360 (1995)

-

Robinson, G. E., Fernald, R. D. & Clayton, D. F. Genes and social behavior. Science 322, 896–900 (2008)

-

Krieger, M. J. B. & Ross, K. G. Identification of a major gene regulating complex social behavior. Science 295, 328–332 (2002)

-

Keller, L. & Ross, K. G. Phenotypic basis of reproductive success in a social insect: genetic and social determinants. Science 260, 1107–1110 (1993)

-

DeHeer, C. J., Goodisman, M. A. D. & Ross, K. G. Queen dispersal strategies in the multiple-queen form of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Am. Nat. 153, 660–675 (1999)

-

Keller, L. & Ross, K. G. Selfish genes: a green beard in the red fire ant. Nature 394, 573–575 (1998)

-

Ross, K. G. & Keller, L. Genetic control of social organization in an ant. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 14232–14237 (1998)

-

Ross, K. G. & Keller, L. Ecology and evolution of social-organization: insights from fire ants and other highly eusocial insects. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 26, 631–656 (1995)

-

Keller, L. & Ross, K. G. Major gene effects on phenotype and fitness: the relative roles of Pgm-3 and Gp-9 in introduced populations of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. J. Evol. Biol. 12, 672–680 (1999)

-

Keller, L. & Ross, K. G. Gene by environment interaction: effects of a single-gene and social-environment on reproductive phenotypes of Fire Ant queens. Funct. Ecol. 9, 667–676 (1995)

-

Lawson, L. P., Vander Meer, R. K. & Shoemaker, D. Male reproductive fitness and queen polyandry are linked to variation in the supergene Gp-9 in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 279, 3217–3222 (2012)

-

Krieger, M. J. B. & Ross, K. G. Molecular evolutionary analyses of the odorant-binding protein gene Gp-9 in fire ants and other Solenopsis species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 2090–2103 (2005)

-

Gotzek, D. & Ross, K. G. Genetic regulation of colony social organization in fire ants: an integrative overview. Q. Rev. Biol. 82, 201–226 (2007)

-

Mather, K. The genetical architecture of heterostyly in Primula sinensis. Evolution 4, 340–352 (1950)

-

Clarke, C. A., Sheppard, P. M. & Thornton, I. W. The genetics of the mimetic butterfly Papilio memnon L. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 254, 37–89 (1968)

-

Joron, M. et al. Chromosomal rearrangements maintain a polymorphic supergene controlling butterfly mimicry. Nature 477, 203–206 (2011)

-

Baird, N. A. et al. Rapid SNP discovery and genetic mapping using sequenced RAD markers. PLoS ONE 3, e3376 (2008)

-

Glancey, B. M., Romain, M. K. S. & Crozier, R. H. Chromosome numbers of red and black imported fire ants, Solenopsis invicta and Solenopsis richteri. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 69, 469–470 (1976)

-

Wurm, Y. et al. The genome of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5679–5684 (2011)

-

Bachtrog, D. et al. Are all sex chromosomes created equal? Trends Genet. 27, 350–357 (2011)

-

Blomquist, G. J. & Vogt, R. G. Insect Pheromone Biochemistry and Molecular Biology: the Biosynthesis and Detection of Pheromones and Plant Volatiles (Academic, 2003)

-

Charlesworth, B. & Charlesworth, D. Elements of Evolutionary Genetics (Roberts & Company, 2010)

-

Bergero, R. & Charlesworth, D. Preservation of the Y transcriptome in a 10-million-year-old plant sex chromosome system. Curr. Biol. 21, 1470–1474 (2011)

-

Wang, J., Ross, K. G. & Keller, L. Genome-wide expression patterns and the genetic architecture of a fundamental social trait. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000127 (2008)

-

Yang, Z. & Bielawski, J. P. Statistical methods for detecting molecular adaptation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 15, 496–503 (2000)

-

Feldman, M. W. & Liberman, U. An evolutionary reduction principle for genetic modifiers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 83, 4824–4827 (1986)

-

Correns, C. Die Rolle der männlichen Keimzellen bei der Geschlechtsbestimmung der gynodiöecischen Pflanzen. Ber. Deut. Bot. Ges. 26A, 686–701 (1908)

-

Bachtrog, D. Expression profile of a degenerating neo-Y chromosome in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 16, 1694–1699 (2006)

-

Nygaard, S. et al. The genome of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex echinatior suggests key adaptations to advanced social life and fungus farming. Genome Res. 21, 1339–1348 (2011)

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Stoffel, C. La Mendola, N.-C. Chang, C.-Y. Kao and C.-C. Lee for helping with genotyping and molecular biology; the DEE-UNIL animal caretakers for ant husbandry; E. Johnson and P. Etter for RADseq advice; R. Nichols, J. Meunier and R. Verity for statistical advice; K. Harshman and M.-Y. Lu for Illumina sequencing support; R. Wang for FISH support; and B. Charlesworth, D. Charlesworth, H. Kaessmann, L. Ometto, J. Pannel, N. Perrin, M. Reuter, P. Reymond and K. Ross for comments. Some computations were performed at the Vital-IT (https://www.vital-it.ch) Center for high-performance computing (HPC) of the SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics and the EPSRC-funded MidPlus HPC centre. This work was supported by the Biodiversity Research Center (Academia Sinica, Taiwan), Taiwan NSC grant 100-2311-B-001-015-MY3, grants from NERC and the BBSRC (BB/K004204/1), a USDA grant, several grants from the Swiss NSF and an ERC Advanced Grant.

Author information

John Wang and Yannick Wurm: These authors contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Lausanne, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland,

John Wang, Yannick Wurm, Mingkwan Nipitwattanaphon, Oksana Riba-Grognuz & Laurent Keller

Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taipei 115, Taiwan,

John Wang & Yu-Ching Huang

School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, London E1 4NS, UK,

Yannick Wurm

Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, CH-1015 Lausanne, Switzerland,

Yannick Wurm & Oksana Riba-Grognuz

USDA-ARS Center for Medical, Agricultural, and Veterinary Entomology, 1600/1700 Southwest 23rd Drive, Gainesville, Florida 32608, USA,

DeWayne Shoemaker

Contributions

J.W., Y.W. and L.K. designed the study and contributed to all stages of the project. M.N., D.D.S. and J.W. prepared samples. J.W. performed RAD sequencing, and J.W. and Y.W. performed genetic analyses. M.N. performed microarray experiments and analysed the data. O.R.-G. and Y.W. analysed RNA-seq and SNP data. J.W. and Y.W. analysed chromosomal locations of differentially expressed genes. Y.W. performed sequence assembly, genome comparisons, and molecular evolution analyses. Y.-C.H. performed FISH experiments. L.K., Y.W. and J.W. wrote the paper with input from other authors.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to John Wang, Yannick Wurm or Laurent Keller.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

-

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Methods and additional analysis, Supplementary References, Supplementary Figures 1-12 and Supplementary Tables 1-6. (.PDF, 1383 kb) -

Supplementary Data

This zipped file contains Supplementary Tables 7-15. (.ZIP, 296 kb)