Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 02 May 2022

Individual-based Modeling of Genome Evolution in Haplodiploid Organisms

Rodrigo Pracana, Richard Burns, Robert L. Hammond, Benjamin C. Haller, Yannick Wurm

Genome Biology and Evolution Volume 14, Issue 5, May 2022, evac062

Abstract

Ants, bees, wasps, bark beetles, and other species have haploid males and diploid females. Although such haplodiploid species play key ecological roles and are threatened by environmental changes, no general framework exists for simulating their genetic evolution. Here, we use the SLiM simulation environment to build a novel model for individual-based forward simulation of genetic evolution in haplodiploids. We compare the fates of adaptive and deleterious mutations and find that selection on recessive mutations is more effective in haplodiploids than in diploids. Our open-source model will foster an understanding of the evolution of sociality and how ecologically important haplodiploid species may respond to changing environments.

Significance

In most species of ants, bees, and wasps, males carry a single copy of each chromosome. In consequence, the effects of natural selection on these species differ from the effects on the many other species in which males have two copies of each chromosome. However, it has not been easy to take this difference into consideration in genomic analysis. Here, we present a method to run computer simulations of genomes of such haplodiploid species. This will allow researchers to make accurate predictions of how bees, ants, and wasps evolve and will help in the interpretation of genomic datasets for these species.

Approximately 15% of all animal species, including ants, bees, wasps, thrips, and bark beetles, have a haplodiploid sex-determination system: haploid, unfertilized eggs develop into males, while diploid, fertilized eggs develop into females (Pamilo and Crozier 1981). These haplodiploid species display a huge diversity of morphologies and behaviors. Furthermore, solitary and social bees occupy essential ecological and agricultural roles as pollinators (Potts et al. 2016), and bees and ants are charismatic models for studying social evolution (Hölldobler and Wilson 1990).

We are only beginning to understand the molecular–genetic bases and constraints underpinning the evolution of haplodiploid species. A key challenge for interpreting genomic data sets from such species is that haplodiploid populations evolve differently from populations of purely diploid individuals. This is because recessive mutations are under the full effect of selection in haploid males but masked from selection in heterozygous diploid males. Such a fundamental difference in how selection works is likely to have important evolutionary consequences, as suggested by analytical models of allelic evolution in simple haplodiploid populations (Avery 1984; Charlesworth et al. 1987; Hedrick and Parker 1997). An important limitation of these models is that they lack the flexibility to consider complex demography and realistic genomic processes including genetic linkage. A solution to this is to use simulations, which have become an essential tool for the theoretical study of evolution and the interpretation of empirical genomic data (Bank et al. 2014). Simulations are used to generate null distributions of common measures of genetic diversity and selection (Voight et al. 2006; Bank et al. 2014; Ferrer-Admetlla et al. 2014), to compare competing hypotheses about the demographic and evolutionary histories of populations (Excoffier et al. 2013; Enard et al. 2014; Adrion et al. 2020), and to predict the effects of environmental changes on different species (DeAngelis and Mooij 2005; Owens and Samuk 2020). The absence of a simulation framework incorporating haplodiploidy has limited the exploration of genomic models of social evolution and the accurate interpretation of population genomic data for bees, ants, and other important species (Favreau et al. 2018; López-Osorio and Wurm 2020; Colgan et al. 2022).

To enable the simulation of genome evolution in haplodiploid organisms, we present an individual-based model built upon the SLiM software framework for forward evolutionary simulations (version 3.7; Haller and Messer 2019). To simulate haplodiploidy, we restricted male individuals to inherit one recombined genome from the female parent and possess an empty “null” second genome. We assigned a relative fitness of 1 + s to male carriers of mutations with selection coefficient s. The Supplementary Text includes more details. Our model can be extended to consider variation in recombination rates, selection, and complex demographic structures.

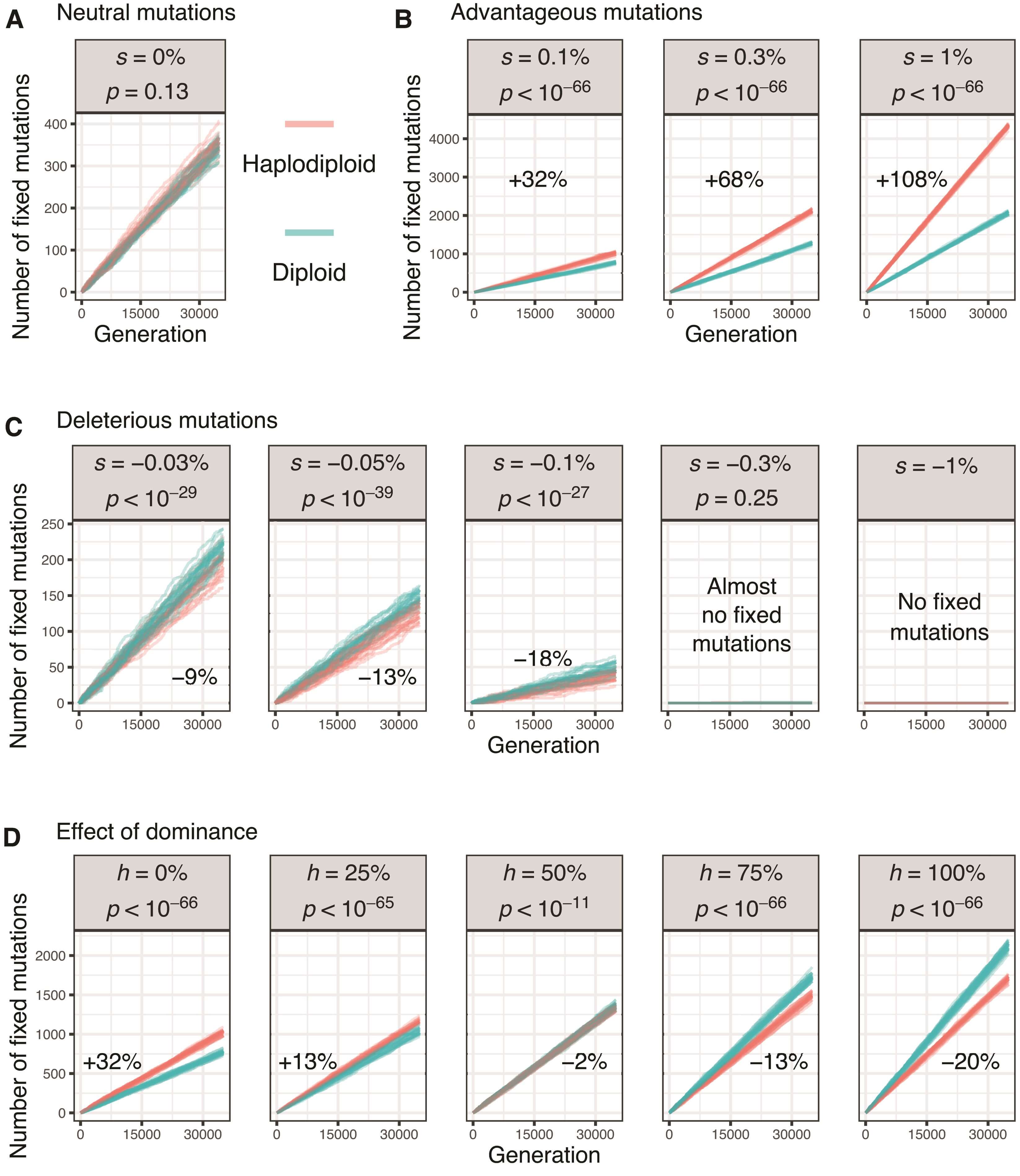

We tested whether our simulations follow the expectations from analytical models (Avery 1984; Charlesworth et al. 1987) by comparing the fates of mutations between haplodiploid and diploid populations. We first modeled neutral mutations (s = 0) in both types of population. As expected from evolution by drift, with a mutation rate of 10-8 on a genome of 106 loci, 0.01 mutations were fixed per generation in both population types (fig. 1A). Because recessive mutations are fully exposed to selection in haploid males but masked in heterozygous diploid males, we subsequently tested whether selection on recessive mutations is more effective in haplodiploid populations (Avery 1984). This was indeed the case: advantageous recessive mutations (s > 0) fixed at a higher rate in haplodiploid populations, with stronger effects in simulations with larger selection coefficients (fig. 1B). Similarly, weakly deleterious recessive mutations (−0.001 ≤ s < 0) fixed at a lower rate in haplodiploid populations (fig. 1C). For more strongly deleterious mutations (s = −0.003 and s = −0.01), very few fixed in either type of population, likely because selection against them overpowered drift (Agrawal and Whitlock 2011; Huber et al. 2018).

Figure.1

The effect of haplodiploidy on the fixation rate of (A) neutral mutations, (B) advantageous mutations, (C) deleterious mutations, and (D) advantageous mutations with different levels of dominance. Each line represents one simulation run (only 20 of 200 shown for each treatment). On each plot, we also show the average difference in the number of fixed mutations between haplodiploid and diploid simulations after 35,000 generations and a burn-in period of 15,000 generations (Wilcoxon rank-sum test; supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). For the simulations in (A) to (C), mutations were fully recessive (dominance coefficient h = 0) and had a range of selection coefficients (s, as shown); for the simulations in (D), mutations had s = 0.001 and a range of dominance coefficients (h, as shown). In (C), < 5% of simulation runs with s = −0.3% and no simulation run with s = −1% had any fixed mutation.

In reality, most mutations are neither fully recessive (dominance coefficient h = 0, as considered in the simulations described so far) nor fully dominant (h = 1) (Orr 2010; Agrawal and Whitlock 2011; Huber et al. 2018). We therefore also compared fixation rates of advantageous mutations between population types across a range of dominance coefficients. For simulations of recessive mutations (h < 0.5), a greater number of advantageous mutations were fixed in haplodiploid populations than in diploid populations (fig. 1D). However, when mutations were dominant (h > 0.5), this pattern was reversed (fig. 1D). This somewhat counterintuitive reversed pattern likely occurs because haplodiploid populations have fewer chromosomes than diploid populations with the same number of individuals (1.5N vs. 2N, for a 1:1 sex ratio). Consequently, fewer mutations enter haplodiploid populations than diploid populations in each generation (1.5Nμ vs. 2Nμ), and thus, fewer mutations can ultimately fix (Charlesworth et al. 1987, 2018). Selection is still expected to be more effective in haplodiploid individuals for any given mutation with h < 1. Indeed, simulations where both population types have identical numbers of chromosomes rather than individuals showed a greater fixation rate for haplodiploid populations, with the magnitude of difference increasing as h decreases (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online).

The ability to simulate the evolution of haplodiploid genomes has the potential to fill major gaps in the study of the demographic and selective processes that have shaped the evolution of haplodiploid species. To date, considerable effort has been made to understand the impacts of haplodiploid reproduction on social evolution, particularly the asymmetry in within-family relatedness inherent to these species and the fact that females can control the sex of their offspring (Meunier et al. 2008). The model presented here will allow us to extend our understanding of the effects of haplodiploidy, for instance through the exploration of the capacity of haplodiploid species to resolve antagonistic selection between sexes or among colony members under different sex ratios (Vicoso and Charlesworth 2009; Eyer et al. 2019). Furthermore, the model will make it possible to test the hypotheses that higher efficacy of selection against recessive deleterious mutations in haplodiploid species may have facilitated the evolution of long lifespans in ant and bee queens and that such higher efficacy of selection may also reduce the degeneration of supergene regions of suppressed recombination (Stolle et al. 2019; Martínez-Ruiz et al. 2020). Our model should help us explore evolutionary processes in haplodiploid species and better understand how interactions between selection efficacy, population size, and migration can affect the ability of haplodiploid species to adapt to environmental change (Potts et al. 2016).

Material and Methods

To be able to control reproduction rules explicitly in SLiM, we implemented our simulations of haplodiploid evolution as a non-Wright–Fisher (nonWF) model using SLiM v3.7. This version facilitates modeling of haploids by extending SLiM’s concept of null genomes to haploidy, and by adding a “haploidDominanceCoeff” property that controls fitness calculations in haploids versus diploids. The Supplementary Text provides modeling details. We compared this model, under different treatments, with a parallel nonWF model of diploid evolution. Because our model defines fitness in terms of reproduction success across non-overlapping generations, our nonWF model of diploid evolution is similar to a Wright–Fisher model (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online).

For each treatment, we simulated 200 populations of 1,000 males and 1,000 females, with genomes of 106 loci, a mutation rate of 10−8, and a recombination rate of 10−6. The levels of dominance coefficient (h) and selection coefficient (s) used for each treatment are given in figure 1. In all cases, mutations had a haploid dominance coefficient of 1. Simulations ran for 35,000 generations after a burn-in of 15,000 generations. The burn-in period is important because haplodiploid and diploid populations with the same number of individuals have different effective population sizes and thus reach mutation–drift balance at different times (supplementary fig. S3, Supplementary Material online). Each simulation took ∼10 min; runtime would likely increase under more complex parameters (supplementary fig. S4, Supplementary Material online).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online.

Acknowledgments

We thank Richard A. Nichols for useful advice. This work was supported by BBSRC (BB/T015683/1) and NERC (NE/L00626X/1, NE/P012574/1). All simulations were run on Queen Mary’s Apocrita computing facility http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.438045.

Author contributions

Conceptualization and supervision, Y.W.; methodology, Y.W., R.B., B.C.H., and R.P.; investigation and writing—original draft, R.P., R.B., and Y.W.; writing—review and editing, R.P., Y.W., R.B., B.C.H., R.H.

Data Availability

Code, analysis scripts, and results of simulation runs are available at https://github.com/wurmlab/haplodiploid_simulations and https://wurmlab.com/data/simulating_haplodiploid_evolution.

Literature Cited

-

Adrion JR, et al. 2020. A community-maintained standard library of population genetic models. eLife 9:e54967.

-

Agrawal AF, Whitlock MC. 2011. Inferences about the distribution of dominance drawn from yeast gene knockout data. Genetics. 187:553–566.

-

Avery PJ. 1984. The population genetics of haplo-diploids and X-linked genes. Genet Res. 44:321–341.

-

Bank C, Ewing GB, Ferrer-Admettla A, Foll M, Jensen JD. 2014. Thinking too positive? Revisiting current methods of population genetic selection inference. Trends Genet. 30:540–546.

-

Charlesworth B, Campos JL, Jackson BC. 2018. Faster-X evolution: theory and evidence from Drosophila. Mol Ecol. 27:3753–3771.

-

Charlesworth B, Coyne JA, Barton NH. 1987. The relative rates of evolution of sex chromosomes and autosomes. Am Nat. 130:113–146

-

Colgan TJ, et al. 2022. Genomic signatures of recent adaptation in a wild bumblebee. Mol Biol Evol. 39:msab366

-

DeAngelis DL, Mooij WM. 2005. Individual-based modeling of ecological and evolutionary processes. Annu Rev Eco Evol Syst. 36:147–168.

-

Enard D, Messer PW, Petrov DA. 2014. Genome-wide signals of positive selection in human evolution. Genome Res. 24:885–895.

-

Excoffier L, Dupanloup I, Huerta-Sánchez E, Sousa VC, Foll M. 2013. Robust demographic inference from genomic and SNP data. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003905.

-

Eyer P-A, Blumenfeld AJ, Vargo EL. 2019. Sexually antagonistic selection promotes genetic divergence between males and females in an ant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 116:24157–24163.

-

Favreau E, Martínez-Ruiz C, Rodrigues Santiago L, Hammond RL, Wurm Y. 2018. Genes and genomic processes underpinning the social lives of ants. Curr Opin Insect Sci. 25:83–90.

-

Ferrer-Admetlla A, Liang M, Korneliussen T, Nielsen R. 2014. On detecting incomplete soft or hard selective sweeps using haplotype structure. Mol Biol Evol. 31:1275–1291.

-

Haller BC, Messer PW. 2019. SLiM 3: forward genetic simulations beyond the Wright–Fisher model. Mol Biol Evol. 36:632–637.

-

Hedrick PW, Parker JD. 1997. Evolutionary genetics and genetic variation of haplodiploids and X-linked genes. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 28:55–83.

-

Hölldobler B, Wilson EO. 1990. The ants. Cambridge (MA): Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

-

Huber CD, Durvasula A, Hancock AM, Lohmueller KE. 2018. Gene expression drives the evolution of dominance. Nat Commun. 9:2750.

-

López-Osorio F, Wurm Y. 2020. Healthy pollinators: evaluating pesticides with molecular medicine approaches. Trends Ecol Evol. 35:380–383.

-

Martínez-Ruiz C, et al. 2020. Genomic architecture and evolutionary antagonism drive allelic expression bias in the social supergene of red fire ants. eLife 9:e55862.

-

Meunier J, West SA, Chapuisat M. 2008. Split sex ratios in the social Hymenoptera: a meta-analysis. Behav Ecol. 19:382–390.

-

Orr HA. 2010. The population genetics of beneficial mutations. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 365:1195–1201.

-

Owens GL, Samuk K. 2020. Adaptive introgression during environmental change can weaken reproductive isolation. Nat Clim Change 10:58–62.

-

Pamilo P, Crozier RH. 1981. Genic variation in male haploids under deterministic selection. Genetics 98:199–214.

-

Potts SG, et al. 2016. Safeguarding pollinators and their values to human well-being. Nature 540:220–229.

-

Stolle E, et al. 2019. Degenerative expansion of a young supergene. Mol Biol Evol. 36:553–561.

-

Vicoso B, Charlesworth B. 2009. Effective population size and the faster-X effect: an extended model. Evolution 63:2413–2426.

-

Voight BF, Kudaravalli S, Wen X, Pritchard JK. 2006. A map of recent positive selection in the human genome. PLOS Biol. 4:e72.

Author notes

© The Author(s) 2022. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

© The Author(s) 2022. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Society for Molecular Biology and Evolution.

Supplementary data

evac062_Supplementary_Data - zip file