Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 14 January 2015

Ant genomics (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): challenges to overcome and opportunities to seize

Sanne Nygaard & Yannick Wurm

Myrmecological News, 2015, 21:59-72

Abstract

Myrmecologists have long studied the systematics, behavior, ecology, and evolution of ants. This first involved fundamental approaches including morphological description or behavioral observation, perhaps with the help of microscopes or marking ants with paint or wire. Many discoveries over the past 20 years have been accomplished with the help of more molecular approaches including allozymes, microsatellites, and chemical analyses, and more recently microarrays. The recent 10,000-fold drop in the cost of DNA sequencing has created new possibilities for myrmecological research. At least ten ant genomes have now been sequenced, with more on the way. Here, we aim to provide an introduction to genomics to the curious myrmecologist. For this, we discuss the genomics analyses possible without a full genome sequence, the motivations, approach and outcomes of a genome-sequencing project, and provide starting points for myrmecologists interested in using genomics data and approaches.

Introduction

Myrmecologists have long studied the systematics, behavior, ecology, and evolution of ants using a range of different approaches. The first included morphological description and behavioral observation, perhaps with the help of microscopes or marking ants with paint or wire. Subsequently, chemical approaches have identified molecules involved in communication (ALI & MORGAN 1990, LENOIR & al. 2001, HOLMAN & al. 2013, OYSTAEYEN & al. 2014), and genetic approaches relying on up to a few dozen markers have clarified relationships within species, e.g., using allozymes (PAMILO & al. 1997) or microsatellites (BOURKE & al. 1997, CHAPUISAT & al. 1997, GYLLENSTRAND & al. 2002), and between species, e.g., using gene sequence phylogenies (BRADY & al. 2006, MOREAU & al. 2006, SCHULTZ & BRADY 2008, WARD & al. 2015). The vast majority of what we know about ants has been accomplished using the aforementioned approaches.

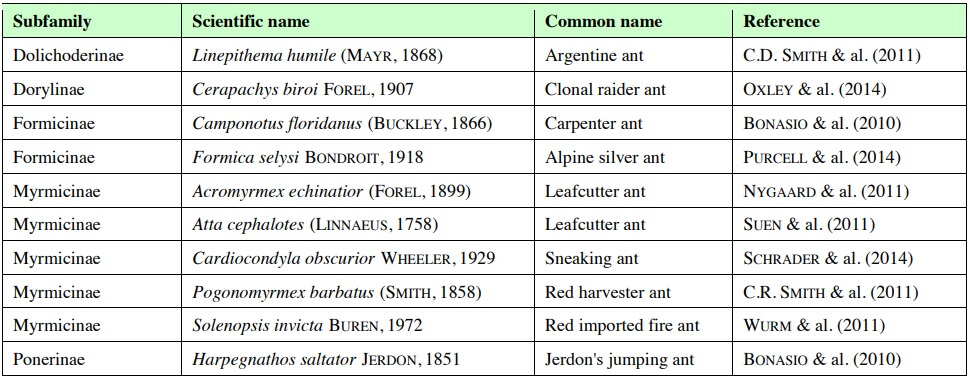

The first research aiming to understand how individual genes are responsible for characteristics of ants focused on small numbers of candidate genes that had been previously identified in other organisms (INGRAM & al. 2005, LUCAS & SOKOLOWSKI 2009, CHOI & al. 2011). The advent of gene expression microarrays around the beginning of this millennium enabled the simultaneous analysis of thousands of genetic markers, marking the first transition towards genome-wide studies of the molecular biology of ants (GOODISMAN & al. 2005, GRÄFF & al. 2007, WANG & al. 2007, GOODISMAN & al. 2008, WURM & al. 2009, WURM & al. 2010). Subsequently, spawned by a dramatic drop in the cost of DNA sequencing (10,000-fold between 2007 and 2014), seven ant genomes were published in 2010 / 2011 (BONASIO & al. 2010, NYGAARD & al. 2011, C.D. SMITH & al. 2011, C.R. SMITH & al. 2011, SUEN & al. 2011, WURM & al. 2011) catapulting myrmecology into the genomics era as more genomes (OXLEY & al. 2014, PURCELL & al. 2014, SCHRADER & al. 2014; see Tab. 1) and analyses of genomics data (Tab. 2) continue to be published.

So what promises does this new era hold for myrmecology? Whereas previous research was generally confined to the study of a few loci or markers, genomics is broadly defined by the use or study of thousands of genetic markers at a time (this upscaling principle holds for other -omics approaches as well). This higher resolution leads to fewer inherent biases, higher specificity and higher sensitivity and thus a greater ability to uncover genetic patterns than traditional approaches (STAPLEY & al. 2010, AMOS & al. 2011, DAVEY & al. 2011, NARUM & al. 2013, BREWER & al. 2014). Genomic approaches thus form a toolbox that can be used to examine the genetic mechanisms behind many biological phenomena. For example, they promise to help us understand relationships within and between species (e.g., phylogenetic, kinship, hybridization), to understand species ecology (e.g., sequencing gut content to identify food sources and symbioses), to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying morphological, physiological, and behavioral differentiation within and between species, and to understand the effects of sociality on genome evolution. Such approaches thus have the potential to significantly enrich and broaden the scope of myrmecology, and are increasingly popular and widespread. Other authors have reviewed some of the exciting results of genomics research on ants (GADAGKAR 2011, GADAU & al. 2012, LIBBRECHT & al. 2013, TSUTSUI 2013) and some such results are detailed in Table 2.

Here, we aim to provide an introduction to genomics to the curious myrmecologist. For this, we discuss in turn the genomics analyses possible without a full genome sequence, the motivations, approach and outcomes of a genome-sequencing project, and provide a starting point for myrmecologists interested in using genomics data and approaches.

Tab. 1 – Overview of currently sequenced ant genomes. An updated list of available ant genomics data can also be found at antgenomes.org.

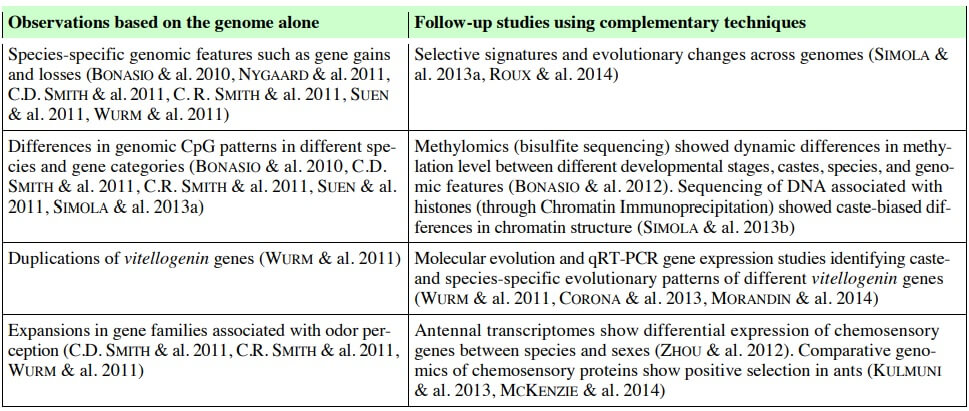

Tab. 2 – Basic analyses of genome sequences can lead to interesting observations, but these generally generate new hypothesis rather than providing clear conclusions. The first column highlights some interesting observations originally based on the genome sequence alone; the second column shows how other studies, using complementary techniques, have expanded on these findings to gain more detailed biological insight.

Can I do genomics without a genome?

Despite drops in sequencing costs, a genome project still represents a significant investment (currently 5,000 to 50,000 € of consumables and several months to several years of analysis). Before embarking on a full genome-sequencing project, it is therefore worthwhile to consider alternative strategies. Indeed, while the term “genomics” seems to imply research firmly centered in the genome sequence itself, genome-scale approaches can also be undertaken without a full genome sequence – for example using reduced representation genome sequencing or transcriptome sequencing. Reduced representation sequencing methods such as RADseq (DAVEY & al. 2011) and RESTseq (STOLLE & MORITZ 2013) consist in sequencing DNA from a subset of hundreds to thousands of genomic locations distributed throughout the genome (perhaps representing 1% of the genome in total) from many individuals simultaneously.

Such high throughput genotyping methods require no genome sequence, the data are less expensive to generate (typically 1,000 to 10,000 €) than a full genome, and require only days of laboratory work (though the subsequent analysis effort and computational costs should not be underestimated – see below and SBONER & al. 2011). These high throughput genotyping methods thus enable rapid sensitive and genome-wide comparisons within and between colonies, populations and closely related species (EMERSON & al. 2010, HOHENLOHE & al. 2010, WANG & al. 2013) and are poised to replace traditional genotyping methods including microsatellites and AFLPs (MCCORMACK & al. 2013).

Another alternative to full genome sequencing is transcriptomics, i.e., the sequencing and assembly of expressed RNA. An assembled transcriptome gives direct information about gene sequences in the genome, which can be used for many applications (MIKHEYEV & al. 2010), including to infer phylogenetic relationships (JOHNSON & al. 2013), to confirm the presence and identify the sequence of particular genes (BADOIN & al. 2013) or pathogens (VALLES & al. 2012), or to discover new microsatellites (MIKHEYEV & al. 2010). Most transcriptome projects enrich for poly-A-tailed RNA transcripts with the lengths among those expected for protein coding genes, thus excluding most non-protein-coding RNA and intronic or intergenic parts of the genome (EKBLOM & GALINDO 2011). An assembled transcriptome is less expensive to generate (typically 500 to 1,000 € for one sample) than an assembled genome, and involves smaller amounts of data. Because of this smaller amount of data and the general focus on proteincoding genes, an assembled transcriptome can be easier to work with than an assembled genome. Transcriptomes from multiple samples (e.g., different castes, developmental stages, tissues or experimental treatments) can provide views of how relative transcript abundance levels (i.e., gene expression profiles) differ between circumstances (BONASIO & al. 2010, SIMOLA & al. 2013b, YEK & al. 2013, FELDMEYER & al. 2014). A genome sequence is neither sufficient nor necessary to provide this kind of dynamic information.

How can a genome sequence help me do my research?

With cheaper and faster alternatives to full genome sequencing, is it really worth sequencing yet another ant genome? Despite the possibilities mentioned above, doing genomics without a genome has some limitations. It can be challenging to interpret patterns identified using reduced representation genome sequencing without knowing the relative positions of the markers used or their relationships to physically associated genes. For example, initial studies based on allozyme markers identified an association between one of these markers, Gp-9, and social structure in Solenopsis invicta fire ants (ROSS & KELLER 1998, KRIEGER & ROSS 2005). A similar analysis using thousands of RADseq markers determined that there is absence of recombination between Gp-9 and hundreds of additional markers, together representing a large part of a chromosome – the two variants of this region thus representing variants of a “social chromosome”. Analysis and comparison of genome sequences of the two variants of this social chromosome showed that the non-recombining region includes more than 600 genes, and that its two variants are evolving similarly to sex chromosomes (WANG & al. 2013). Such detailed insight would have been impossible without genome sequencing.

Similarly, an assembled transcriptome has at least three shortcomings when used without a full genome sequence. First, a transcriptome only contains sequence for genes that are expressed in the sample from which it was produced, thus otherwise important gene sequences may be absent. Second, transcriptome quality is heterogeneous with putative transcripts for highly expressed genes being of higher quality than those for lowly-expressed genes which are often fragmented. Third, it is often impossible to determine whether similar sequences in a transcriptome assembly represent alternate alleles of a single gene, alternate splice-variants (isoforms) of a single gene, different but closely related genes (e.g., recent paralogs), sequencing or assembly artifacts or combinations of these cases. An assembled genome sequence can help to resolve many such ambiguities and can facilitate interpretation. Likewise, many other highly-molecular research approaches based on -omics data – including studying some epigenetic aspects of caste differentiation (CHITTKA & al. 2012, SIMOLA & al. 2013b) – rely on a genome sequence (PARK 2009, FLORES & AMDAM 2011, LI & CHURCH 2013).

A sequenced genome forms a reference for the analysis of data obtained from other molecular markers or -omics type approaches (including those mentioned above). Furthermore it also greatly facilitates some more traditional molecular or genetics work. For example, extracting microsatellite markers from genomic sequences is an accessible alternative to laborious microsatellite library construction protocols (FAIRCLOTH 2008, GARDNER & al. 2011, BUTLER & al. 2014). Similarly, performing molecular phylogenies or studying the expression of candidate genes has often required tedious attempts at PCR with degenerate primers (FITZPATRICK & al. 2005); it is faster and easier to extract relevant sequence from an assembled genome sequence, in particular when focusing on multiple, closely related genes (GÓNGORA-CASTILLO & BUELL 2013). A genome sequence in itself also provides ample phylogenetic data for clarifying relationships between closely or distantly related species (MCCORMACK & al. 2013). Comparative genomic studies also provide opportunities to understand how evolutionary forces have acted at the molecular scale, and how evolution has shaped the genome over time (ELLEGREN 2013). For example, analyses of signatures of selection can reveal which genes were under positive selection for novel functionality (ROUX & al. 2014). Similarly, the study of genome dynamics such as duplications or losses of particular genes, changes in regulatory networks, or the emergence of new genes (SIMOLA & al. 2013a, SUMNER 2014), can identify the molecular basis for species specificities. Such analyses promise to help us finally bridge the gap between genotypes and the molecular mechanisms underlying the diverse phenotypic traits of ants.

A genome-sequencing project is thus not just a study in itself, but also an investment in a valuable resource for future research on the focal species, but also for research on other species. Indeed, a genomic reference sequence from a related species can – with small evolutionary distances – be sufficient for e.g., transcriptome mapping or constructing primers in conserved regions. At a different level, the power of comparative genomics relies on having many genomes available for comparison, thus ant researchers as a community will benefit from having more available ant genomes with broader taxonomic sampling.

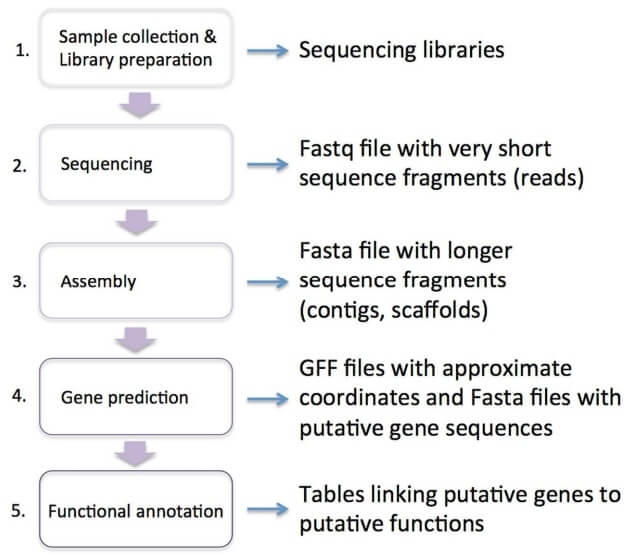

Fig. 1

The five steps involved in most genome projects: First, biological material is collected and the DNA and RNA are extracted and processed into sequencing libraries. Second, the libraries are sequenced, and the outputs from the sequencing machine (after much data filtering) are saved as a text file of inferred sequence "reads", typically in a FASTQ format text file. Third, based on sequence overlaps between reads, longer stretches of contiguous sequence ("contigs") are reconstructed and these contigs "strung together" into "scaffolds" representing chromosomal fragments. These contig and scaffold sequences are what is termed "the assembly". Fourth, in the gene feature annotation phase, automated programs and procedures are used to predict the approximate location of genes within the assembly (usually incorporating transcriptome data). Fifth, putative functions are assigned to the predicted genes based on homology to other species or prediction of conserved protein domains.

How do I obtain a genome and what will it look like?

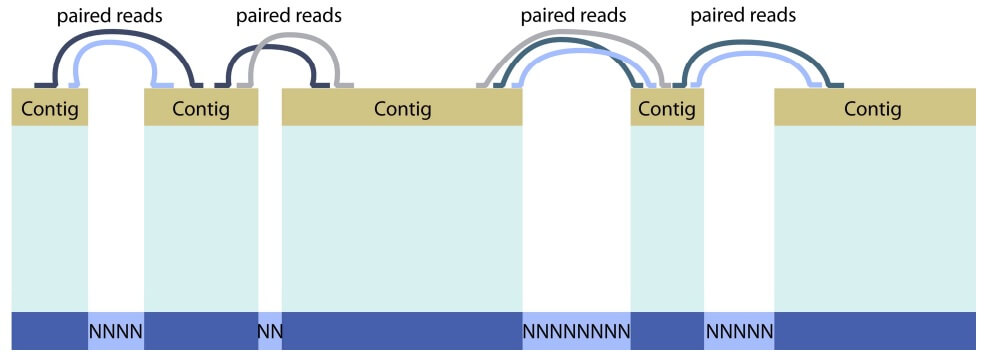

Obtaining a genome sequence involves five main steps (see Fig. 1), each of which should consider information including genome size, repetitiveness, local resources and the aims and immediate applications of the sequencing project. Ideally, DNA sequencing efforts focus on a single haploid male because assembly and analysis tools perform best if the samples have low genetic diversity (VINSON & al. 2005). In addition, a diverse set of samples (e.g., different castes and developmental stages) is simultaneously used for RNA sequencing to help subsequent gene identification. The first step is thus to obtain appropriate samples, extract high quality DNA (in the order of 100µg for a genome-sequencing project) and RNA (1-5µg per sample for transcriptome sequencing), and construct sequencing libraries. Importantly, high quality unfragmented DNA and RNA are needed; they are best obtained from fresh samples flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen; it is challenging to obtain high quality DNA – and impossible to obtain high quality RNA – from samples stored in ethanol. The second step is sequencing of the libraries, resulting in billions of nucleotide sequences (“reads”) in fragments from 50 to 2,000 nucleotides long; newer technologies are beginning to provide substantially longer sequences (MARX 2013a). Third, a genome is assembled, which essentially means that the original genome sequence is reconstructed based on overlaps between the short DNA sequences. Unfortunately, repetitive sequences (transposons, microsatellites, minisatellites) as well as heterozygosity (e.g., due to allelic variation) make these overlaps ambiguous, so that it is often impossible to correctly infer the order or align all sequence reads. Thus, it is impossible for current sequencing and assembly approaches to provide a single long sequence per chromosome (although novel long-read technology may be changing this; see KIM & al. 2014). Instead, the genome assembly consists of a few hundred to several thousand “scaffolds”, i.e., DNA sequence stretches each of which should represent a chromosomal fragment. In practice, because of technological and algorithmic challenges, these reconstructed sequences contain some errors, and portions of the true chromosomes will be missing (Fig. 2). The scaffold sequences are provided in a single large text file in FASTA format (see Box 1), but this sequence alone is generally of limited use without additional information.

After assembly, most genome-sequencing projects pursue a fourth and fifth general step before beginning analyses. A challenging step is identifying locations of genes within scaffolds (ELSIK & al. 2014): Specialized gene prediction software can identify potential gene sequences by combining information from RNA sequence (usually sequenced at the same time as the genome as described above), gene sequences known from other species, and statistical properties of genes (e.g., codon usage, intronexon boundaries). This results in gene prediction files showing gene coordinates on the genome scaffolds (text files in GFF or GTF format; see Box 1), as well as FASTA files respectively containing the predicted mRNA and protein sequences of predicted genes. Caution is required when using these sequences however, as information regarding alternative splicing is unavailable for most genes, and crucially many gene predictions contain errors (e.g., they are erroneously split into multiple genes or merged with other genes – see YANDELL & ENCE 2012, DENTON & al. 2014 and considerations below). As a final step, the predicted genes are functionally annotated, i.e., their names and potential functions are inferred based on names and functions of similar genes in other organisms (RHEE & al. 2008, PETTY 2010, YANDELL & ENCE 2012). Here again, automated annotation is an error-prone process: Many genes have no identifiable homologs with known functions in any organism, and for those that do, the inferred functions should be considered tentative guesses. Indeed, most genes have only been studied in distantly related organisms such as fruit flies or yeast, and may function differently in ants. Overall, a genome thus consists of a set of text files containing approximate sequences, coordinates and potential gene functions. This is when the actual analysis work to gain publishable biological insight begins.

What can the genome tell us?

The analysis of a newly sequenced genome usually starts with the calculation of several general statistics that characterize core features of the genome assembly. These include numbers such as the size of the assembled genome, metrics that assess the assembly quality (e.g., coverage, N50), the GC-content, the distribution of repetitive sequences, the number of predicted genes, and other measurements of genome quality (see Box 1 for details). The interest for such statistics – beyond indicating genome assembly quality – has waned now that we have a fair idea of what to expect from an ant genome. Indeed, obtaining a high-impact publication based on genome sequencing today requires obtaining exceptional biological insight (FLOT & al. 2013, NYSTEDT & al. 2013). Thus the most exciting genomic research will be driven by specific hypotheses rather than by the desire to generate large amounts of data. Rather than adding to the recent reviews detailing how genomes have successfully been used in myrmecological research (GADAGKAR 2011, GADAU & al. 2012, LIBBRECHT & al. 2013, TSUTSUI 2013), we provide ideas concerning approaches taken to identify potentially interesting features in a newly sequenced genome, and to appropriately follow up on them.

Fig. 2

Five contigs are joined into a single scaffold thanks to paired read information. Overlaps between individual sequence reads allow the reconstruction of contiguous stretches of genomic sequence ("contigs"), but unsequenced regions (gaps, where no reads exist for the genomic DNA) or repetitive regions (where reads cannot be assigned to one unique contig) generally prevent these contigs from being more than a few thousand bases long. Instead, the relative placement of individual contigs is inferred by using so-called paired reads (pairs of short reads separated by a known distance such as 40,000 bp) to bridge the gaps across non-sequenced or repetitive regions. These longer pieces of reconstructed sequence (generally in the megabase range) are termed "scaffolds" and will usually contain long stretches of "N"s representing the inferred approximate length of gaps / repetitive sequence between contigs.

In some cases, explicit hypotheses concerning particular candidate genes or genome features may exist for a study species. Such hypotheses, e.g., concerning the sequence or number of particular genes, can be checked directly once the genome is available. For example, the identification of the sex determination locus in honey bees (BEYE & al. 2003) inspired others to look at the homologs of this gene in ant genomes (PRIVMAN & al. 2013, KOCH & al. 2014). Similar work has been done on other genes including clock genes (INGRAM & al. 2012), the foraging gene (LUCAS & al. 2015), chemosensory genes (KULMUNI & al. 2013) and desaturase genes (HELMKAMPF & al. 2015). Another widespread approach consists in so-called “fishing expeditions”, semi-automated data mining approaches with the aim of identifying interesting features without any explicit hypotheses. A first implementation of this approach involves comparing the number of genes within each known gene family between the newly sequenced genome and other, previously published genomes. This approach determined that two key enzymes in the Arginine biosynthesis pathway were lost in two leaf-cutter ant genomes (NYGAARD & al. 2011, SUEN & al. 2011) suggesting that these ants may depend on their symbionts for this amino acid. The same approach determined that ants have higher numbers of olfactory receptors than other insects (C.D. SMITH & al. 2011, C.R. SMITH & al. 2011, WURM & al. 2011), consistent with the relatively greater importance of chemical communication in ant colonies. Finally this approach also determined that the Solenopsis invicta genome contains four copies of a central gene in the control of reproduction and behavior, the vitellogenin gene (WURM & al. 2011), suggesting that workers and queens could use different copies of this gene (CORONA & al. 2013). Though such genome-based findings are rarely conclusive in themselves, they provide starting points for investigating the genomic underpinnings of specific aspects of ant biology.

A second type of “fishing expedition” consists in molecular evolution comparisons without explicit hypotheses. These can characterize the selective forces (purifying / positive) that have acted on whole genomes or specific groups of genes (HUNT & al. 2011, KULMUNI & al. 2013, SIMOLA & al. 2013a, ROUX & al. 2014). For example, this approach determined that genes with mitochondrial functions repeatedly underwent positive selection during ant evolution, suggesting that mitochondrial function has adapted to changes in ant life style (ROUX & al. 2014). Finally, large scale analysis of DNA sequence motifs can shed light on genome-wide processes. For example, the identification of putative transcription factor binding sites across a genome can hint at potential gene regulatory processes (BONASIO & al. 2010, SIMOLA & al. 2013a). Likewise, the distribution of CpG sites (see Box 1) can clarify historical methylation levels, thus hinting at gene regulatory processes over time (GLASTAD & al. 2014).

Box 1: Definitions.

- Annotation: 1. Gene Feature Annotation: Identifying the locations of genes in a genome. 2. Functional Annotation: the assignment of (inferred) function to a specific location within the genome, or to the transcripts deriving from that location.

- Assembly: The attempted reconstruction of a single genome (or transcriptome) sequence from large numbers of short individual sequence reads.

- ChIP-Seq, Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing: Targeted sequencing of stretches of DNA that are bound to histones, or other chromatin associated proteins. Antibodies are used to pull out the proteins of interest, and the DNA they bind to, prior to the sequencing.

- Coverage: Usually used to refer to the "depth" of sequencing, meaning how many times a given position in the genome (or transcriptome) has been sequenced. Due to the random nature of the sequencing procedure, some positions will be sequenced many times, while others will be missed. The coverage reported for full genomes is an average or peak value.

- CpG site: A cytosine followed by a guanine in a DNA sequence. The cytosine in such a CpG site can become methylated (a methyl group is added to the 6-atom ring), which in turn can affect the expression levels of nearby genes. Methylated cytosines are more prone to mutation, meaning that in highly methylated genomic regions CpG sites tend to become depleted over evolutionary time.

- FASTA: text file format for specifying biological sequences, typically DNA or protein. Each entry consists of one identifier-line (always starting with a ">"), specifying the name of the sequence, followed by one or more lines of actual sequence. In addition to a fasta file, genome assemblies will generally also include a more technical text file (termed an AGP file), which specifies the order of contigs and estimated lengths of gaps

- FASTQ: A FASTA format text file which additionally contains a line specifying quality scores for each position in a sequence. These quality scores reflect the certainty of each individual base call.

- GC-content: The Guanosine-Cytosine (GC) content of a genome is the percentage of basepairs that are either G or C. This percentage varies between genomes, and also between different types of functional regions within a genome (e.g., exons versus introns). Very high or very low GC content makes a genome more difficult to both sequence and assemble

- GFF, GTF: File formats widely used in genome annotation. The files are plain text, each line separated into tab-delimited columns that give standard information such as scaffold ID and position within the scaffold for a particular genomic feature (e.g., genes, exons).

- Methylomics: Genomic methylation patterns affect gene regulation, and can be assessed using sequencing. Prior to sequencing, the DNA is chemically treated with bisulfite so that unmethylated cytosine residues are converted to uracil. The methylated sites can then be inferred by comparing the converted reads to a non-treated reference sequence. The technique is also referred to as bisulfite sequencing or BS-seq.

- N50: A statistic used to assess how fragmented an assembly is. Can be thought of as an adjusted median scaffold length. It is the size of the smallest contig / scaffold such that 50% of the total assembly length is contained in contigs / scaffolds of this size or longer.

- NGS: Next Generation Sequencing. A term used to describe the new sequencing technologies (starting with 454 and Illumina) that allowed a significant decrease in sequencing costs. Other commonly used terms are "second generation sequencing" and "high-throughput sequencing".

- RAD-Seq, Restriction-site associated DNA sequencing: A protocol where genomic DNA is digested with specific restriction enzymes and subsequently sequenced, targeting specifically the region around the cut sites. The same random, genomic subset can thus be sequenced from several individuals, assuming the restriction sites have been conserved. REST-Seq is a related method; there are many additional variants.

- Repeats / repetitive sequence: There are two general classes of repetitive sequence in genomes: Simple repeats such as microsatellites are repeating sequences of a few basepairs. The number of repetitions can be highly variable between individuals. Transposons are more complex genetic elements. Many types of transposons exist, and multiple copies of each type can be present in a genome. They are frequently pseudogenized / degenerate and thus hard to identify. Both types of repeats complicate assembly, but can also play important roles in genome evolution.

- Scaffold: The result of genome assembly, scaffolds are the reconstructed sequence stretches that ideally each correspond to a particular stretch of chromosome. Scaffolds may contain gaps of unknown sequence (typically repetitive sequence; see Fig. 2). Stretches of contiguous sequence with no gaps are termed "contigs".

- Sequencing library: When DNA or RNA has been extracted and processed into a molecular construct ready for sequencing with a NGS technology. This generally involves cDNA construction (for RNA samples), fragmentation, size separation, ligation to flank sequences, and PCR amplification.

- Transcriptome: The total expressed RNA, either in a whole organism, or in a particular tissue and / or under a certain condition. Transcriptome sequencing usually focuses on the mRNA portion of the RNA, but can also specifically target e.g., small RNAs. Transcriptome assembly ideally reconstructs the original transcripts from start to end, but this is complicated by alternative exon use, highly variable transcript abundances, and spurious transcripts.

In many cases genome sequence analysis is a step towards identifying or refining hypotheses rather than fully addressing them. This is because a genome sequence is an approximate, static, one-dimensional representation of the complete genetic information of an entire organism. In contrast, most biological phenomena are dynamic processes, and the use of the genetic information may differ hugely between tissues, developmental stages, individuals or environmental conditions. The investigation of such dynamic processes requires applying additional techniques to follow up on the findings from the genome analyses. For example, directed qRT-PCR was used to identify the caste-biased expression patterns of vitellogenins (CORONA & al. 2013). Likewise, while genomic comparisons identified potential signatures of differential DNA methylation within and between ant genomes (BONASIO & al. 2010, C.D. SMITH & al. 2011, C.R. SMITH & al. 2011, SUEN & al. 2011, SIMOLA & al. 2013a), direct sequencing of methylated DNA demonstrated differential methylation between castes and species (BONASIO & al. 2012). Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and subsequent sequencing of DNA associated with different post-translationally modified histones and other core chromatin proteins likewise identified caste-specific differences (SIMOLA & al. 2013b). Table 2 shows some examples of how ant genomes were used to make initial observations, and how additional studies, using complementary techniques, have expanded on these observations. For more specific examples of how genomes have been used in ant research, see recent reviews (GADAU & al. 2012, LIBBRECHT & al. 2013, TSUTSUI 2013).

Before beginning a genomics project

Entering a new field such as genomics is exciting but can also be challenging. To avoid some common pitfalls, the five points below are worth considering when beginning a genomics project.

First, genomics laboratory techniques, genome assembly, gene prediction, gene function annotation, gene expression analysis and population genomics are entire research fields, each involving specific technical knowledge and contributing challenges in terms of experimental design, troubleshooting and interpretation. Thus ensuring that all work is performed to a high standard is easiest with a large research team including experienced collaborators (including some with experience from non-Drosophila arthropods), who can provide input already during the project planning. While some larger laboratories have permanent in-house data scientists (DAVENPORT & PATIL 2012) to assist with analysis, this is likely still unrealistic for most. If large parts of the analyses are to be done by temporary staff such as Ph.D. students or Post Docs, it is necessary to both set aside time and budget for their formal training, and to ensure that their acquired expertise is retained in the group once they leave. Fully harnessing the power of genomics requires balancing the tradeoff between two skills: On one hand the computational and bioinformatics skills required to query the data with knowledge of their potential shortcomings, and on the other hand having the biological insight and motivation to critically interpret the results in a biologically informed manner. It is easy to lose large amounts of time either by analyzing data without a clear goal, or by aiming for data qualities similar to those of the Drosophila or human genomes – which is infeasible for a small team. An efficient approach is to follow Pareto’s principle: putting energy into the 20% of potential tasks that will lead to 80% of the potential results (JURAN 1951).

Second, a clear research hypothesis is just as important to a genomics project as to other research. A clear goal helps in determining the most appropriate technology, whether it is genome sequencing, RADseq, transcriptome sequencing, or other. Similarly, it is worth considering beforehand if there will be sufficient statistical power to detect the expected signal and reach conclusions. In particular, genomic analyses typically involve many parallel tests, and thus require large amounts of statistical correction for multiple testing. As with any other experiment, precautions thus need to be made to avoid insufficient sample sizes and introduction of confounding factors which could lead to irreproducible results (FANG & CUI 2011). External factors can also be important – such as the presence of data from relevant outgroup / comparison species and their evolutionary distance. Regardless of the research question, an analysis plan should be relatively clear before starting to collect samples for sequencing.

Third, it is important to have realistic expectations about the genome project output. As mentioned above, genome assemblies now generated within weeks or months by small groups of researchers are highly fragmented. Such genome assemblies are sufficient for answering some questions, but remain of far lower quality than those generated over decades by collaborations between large institutes (e.g., the human and Drosophila melanogaster genomes). Obtaining high-quality assemblies still requires substantial additional investment (STEMPLE 2013). Fragmented and errorprone assemblies exacerbate difficulties with gene identification and with inferring gene loss or duplication. Potentially interesting discoveries may easily prove to be errors introduced by sequencing, assembly and annotation algorithms, and thus manual verifications of potentially interesting genes are generally needed (YANDELL & ENCE 2012, DENTON & al. 2014). This can take dozens or even thousands of hours. Furthermore, the functions of most ant genes are either unknown or are inferred based on the functions of homologous genes in traditional laboratory organisms such as yeast or D. melanogaster – the evolutionary distances involved can make it challenging to trust some inferred functions and thus to specifically interpret results.

Fourth, many challenges come from the fast pace at which new genomics tools are created: The standard sequencing, assembly or analysis approach from two years ago may already be obsolete, thus reviews of such topics and technological comparisons (SALZBERG & al. 2012, BRADNAM & al. 2013) – while very helpful – should be viewed critically. Again, collaborators with expert knowledge can help clarify whether particular new technologies will accelerate or facilitate analysis, or create unnecessary complications and delays. Furthermore, it is preferable to get all data at once, so that everything is sequenced using the same reagents and protocols, because technical differences and batch effects can make it challenging to merge or compare data across experiments (FINSETH & HARRISON 2014, SU & al. 2014). Similarly, fast technological developments mean that newly generated data rapidly loses the benefit of scientific novelty, thus creating incentives for rapid analysis and publication.

Finally, much genomics work requires specialized computing hardware and software. While the software is generally free, costs to access appropriate hardware can exceed those for sequencing (SBONER & al. 2011). Many universities provide research computing core facilities – these may be inappropriate for genomics if their focus is on historically established computational sciences such as physics (LEIPZIG 2011, APPUSWAMY & al. 2013). Such core facilities often charge for processing time, storage, support and systems administration – which ensure that everything is running and backed up appropriately and that necessary software is installed. If appropriate computational infrastructure is not locally available, cloud-based computational infrastructure providers can provide on-demand access to storage and computing power (STEIN 2010, BIOSTARS 2013, MARX 2013b).

Learning to analyze genomics datasets

Datasets throughout the biological sciences are growing beyond what can be processed using spreadsheet software, making the ability to handle large datasets an essential skill for biologists (GROSS 2011, NATURE CELL BIOLOGY EDITORS 2012). This is even more true for genomics, as even small projects now involve hundreds of gigabytes of DNA sequence data. As a further challenge, genomics data analysis is still young and draws from a broad range of knowledge from different fields (SEARLS 2012, WELCH & al. 2014), with analysis tools and constraints varying extensively between and within projects.

Some software is being developed with graphical “pointand-click” interfaces that allow researchers to easily perform analyses on their own datasets. For bioinformatics analyses, Galaxy (GOECKS & al. 2010) is the most popular such tool and includes the most up-to-date software. However, such tools are generally restricted to relatively basic usage cases and often include only old versions of established algorithms and tools. Using graphical interface tools to analyze data from more complex experimental designs or using up-to-date software that works best with the latest data types can be challenging or even impossible.

Classically trained biologists wishing to incorporate genomic approaches as a stable feature of their future research will therefore benefit from learning some core tools of bioinformatics: How to use the UNIX commandline, how to create analysis pipelines and process text with a scripting language, how to appropriately do statistics and process numbers with R, and how to ensure that data and results are correct and accessible. Useful work can be performed within days or weeks of beginning to use such tools, but harnessing their full power takes years. Importantly, trying to master them will help develop the computational way of thinking required for bioinformatics analyses (SCHATZ 2012, LOMAN & WATSON 2013).

The UNIX command line: Most bioinformatics tools run only on UNIX computers, and most high performance computing infrastructures run on the Linux flavor of UNIX (sub-flavors include BioLinux, Ubuntu and Redhat). Fortunately, Apple’s MacOS X is a flavor of UNIX, and on Windows machines it is possible to either connect to UNIX machines using “SSH client” software, to use Linux tools within Windows by installing Cygwin (cygwin.com) or to install Linux within the free VirtualBox software (virtualbox.org) – we recommend BioLinux (FIELD & al. 2006) which comes preloaded with a wide array of bioinformatics tools. Connecting to servers, moving files, installing software, running software and visualizing output using the UNIX command-line is an essential basis for bioinformatics work (LOMAN & WATSON 2013).

Choose a scripting language: Bioinformatics work frequently requires transferring the output from one piece of software into the next one. This may need to be repeated many times (e.g., once per sample or set of parameters), and often the output needs to be reformatted. Automating such tasks with scripts – a central need in bioinformatics – can free up time and reduce the risks of making mistakes (DUDLEY & BUTTE 2009). The first scripting language widely used for bioinformatics was Perl (perl.org, bioperl.org; STAJICH & al. 2002) because it offers fast and flexible text manipulation capabilities. For historical reasons many existing scripts for genomic data manipulation are coded in Perl, so familiarity with this language can be helpful. However, Perl syntax can be arcane or even incomprehensible so beginners should expect a steep learning curve. The Python and Ruby languages are popular alternatives that were specifically designed to make life easier for programmers by overcoming many shortcomings of Perl. In particular, these languages require fewer symbol characters, don’t require confusing concepts such as referencing and dereferencing, and are object oriented, a programming paradigm that makes the mix-and-match of code blocks easy (LEWIS & LOFTUS 2008). Python (python.org, biopython.org; COCK & al. 2009) has a good user base, and sufficient bioinformatics code available for most common bioinformatics tasks. Ruby (ruby-lang.org, bioruby.org; GOTO & al. 2010) continues the trend from Python, having (its proponents say) even clearer and more easily written and understood code (MATSUMOTO 2000). The number of biologists using Ruby has been growing steadily (BONNAL & al. 2012). Several even younger programming languages – designed with particular strengths in working with large dynamic datasets, distributed datasources or parallel processing are now only emerging for bioinformatics (bionode.io, julialang.org). In practice, the choice of programming language often depends on the support you can find from colleagues. Additionally, there are a plethora of programming books and online resources to learn from, and much assistance to be had via online forums (e.g., DALL’OLIO & al. 2011; links can be found via the programming pages mentioned above). Importantly, many concepts are shared between programming languages, thus switching from one to another is easier than learning from scratch.

Learn statistics and R: Ecologists and evolutionary biologists have long known the importance of statistics. Most genomic datasets feature more measurements (e.g., hundreds of thousands of data points) than samples (e.g., tens or hundreds of individuals), thus creating different statistical contexts than those typical in ecology. The free statistics analysis environment R (r-project.org; R CORE TEAM 2014) is the standard analysis environment in most public and many private institutions: It immediately meets most basic statistical needs, many free add-on packages are specifically aimed at analysis of genomics data (bioconductor.org; GENTLEMAN & al. 2004), and it provides the R programming language for automation. Despite this language having a steep learning curve, this makes R a powerful context for processing numbers. Unfortunately, R cannot appropriately substitute for the scripting languages mentioned above because it is less appropriate for processing text or building bioinformatics pipelines.

Analysis reproducibility and accessibility: Small mistakes leading to incorrect results can be costly for the person making the mistakes (MILLER 2006), collaborators and the research community as a whole; the risk of such mistakes going undetected is even higher with large datasets than with small ones. It is thus important to consider different potential sources of errors and take steps to reduce such risks. Approaches to do this include rigorous automated testing, and making data and analysis scripts easily accessible and reusable (software.ac.uk, CROUCH & al. 2013, WILSON & al. 2014). Importantly, in addition to increasing confidence in the results, these approaches lead to higher impact within and beyond the immediate scientific community (PIWOWAR & VISION 2013).

Some fluency in the above general skills should make it possible for a biologist to confidently identify and use the specific tools needed to analyze a particular dataset. As indicated above, the web contains a plethora of tools, tutorials and documentation that makes self-study possible. For a biologist wanting more structured or theoretical studies, many bioinformatics MSc courses catering specifically to biologists now exist, and whole courses in various fields of bioinformatics can also be found online (e.g., through the education portal coursera.org).

Conclusion

Genomic approaches have already created a new frontier in myrmecology, promising exciting new possibilities for researchers who master these tools. The decreasing costs and rapid technological developments mean that largescale studies are now within reach of even smaller labs. However, a researcher starting up a genomics project should not underestimate the task before them, or the substantial support and resource allocations that are required for such a project to succeed. While descriptive, exploratory research was possible for the first genome sequences, the most exciting upcoming discoveries will likely be driven by clearly formulated research hypotheses. To ease the learning curve when starting out with genomics, we recommend first asking new questions using already existing ant genomics data (WURM & al. 2009, MUNOZ-TORRES & al. 2011), or generating small amounts of data (e.g., RADseq or a transcriptome) before moving on to larger-scale projects.

Genomic approaches cannot replace traditional experimental and observational studies, but the combination of clever experimental designs and genomic tools will allow us to link behavioral, developmental and physiological traits to their genetic basis, and study the evolution of social life in far more detail than what was previously possible. As a small word of caution, identifying genes that show correlations to a biological trait can be easier than determining whether these genes are actually responsible for the trait – a fundamental aim of much genomic research. Indeed, demonstrating causality requires functional verification. This can involve artificially inactivating the gene using approaches such as RNA interference (SCOTT & al. 2013), artificially activating it or modifying its sequence using transgenic approaches such as Crispr / CAS (RAN & al. 2013), or manipulating pathways using pharmacological approaches (WILLOUGHBY & al. 2013). RNA interference has been reported in ants (e.g., LU & al. 2009, CHOI & al. 2012, MIYAZAKI & al. 2014), but overall these functional verification approaches remain more challenging to implement in ants than in many other organisms such as Drosophila. This is due to several traits of ants including the inability to breed many ants in the laboratory, their long generation times, the subsequent difficulty of performing specific crosses or creating genetic lines, the fact that most diploid eggs develop into non-reproductive workers with no simple way of modifying their developmental destiny, and the difficulty of accurately quantifying many behavioral phenotypes. The most ambitious projects will thus require interdisciplinary collaboration for experimental design, data analysis, result interpretation and follow-ups. With so many new tools at our disposal, and a strong tradition for inquisitive research into core aspects of biology, the future promises well for myrmecology.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their thanks to Alexander (Sasha) Mikheyev, Oksana Riba-Grognuz, Rachelle Adams and an anonymous reviewer for comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. SN is funded by the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF57). YW is funded by BBSRC grant BB/K004204/1, NERC grant NE/L00626X/1, and is a fellow of the Software Sustainability Institute.

References

-

ALI, M.F. & MORGAN, E.D. 1990: Chemical communication in insect communities: a guide to insect pheromones with special emphasis on social insects. – Biological Reviews 65: 227-247.

-

AMOS, W., DRISCOLL, E. & HOFFMAN, J.I. 2011: Candidate genes versus genome-wide associations: which are better for detecting genetic susceptibility to infectious disease? – Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 278: 1183-1188.

-

APPUSWAMY, R., GKANTSIDIS, C., NARAYANAN, D., HODSON, O. & ROWSTRON, A. 2013: Nobody ever got fired for buying a cluster. – Microsoft Research Technical Report MSR-TR-2013-2.

-

BADOUIN, H., BELKHIR, K., GREGSON, E., GALINDO, J., SUNDSTRÖM, L., MARTIN, S.J., BUTLIN, R.K. & SMADJA, C.M. 2013: Transcriptome characterisation of the ant Formica exsecta with new insights into the evolution of desaturase genes in social hymenoptera. – Public Library of Science One 8: e68200.

-

BEYE, M., HASSELMANN, M., FONDRK, M.K., PAGE, R.E. & OMHOLT, S.W. 2003: The gene csd is the primary signal for sexual development in the honeybee and encodes an SR-type protein. – Cell 114: 419-429.

-

BIOSTARS 2013: List of cloud genomics companies. – <biostars.org/p/86463>, retrieved on 28 January 2015.

-

BONASIO, R., LI, Q., LIAN, J., MUTTI, N.S., JIN, L., ZHAO, H., ZHANG, P., WEN, P., XIANG, H., DING, Y., JIN, Z., SHEN, S.S., WANG, Z., WANG, W., WANG, J., BERGER, S.L., LIEBIG, J., ZHANG, G. & REINBERG, D. 2012: Genome-wide and castespecific DNA methylomes of the ants Camponotus floridanus and Harpegnathos saltator. – Current Biology 22: 1755-1764.

-

BONASIO, R., ZHANG, G., YE, C., MUTTI, N.S., FANG, X., QIN, N., DONAHUE, G., YANG, P., LI, Q., LI, C., ZHANG, P., HUANG, Z., BERGER, S.L., REINBERG, D., WANG, J. & LIEBIG, J. 2010: Genomic comparison of the ants Camponotus floridanus and Harpegnathos saltator. – Science 329: 1068-1071.

-

BONNAL, R.J.P., AERTS, J., GITHINJI, G., GOTO, N., MACLEAN, D., MILLER, C.A., MISHIMA, H., PAGANI, M., RAMIREZ-GONZALEZ, R., SMANT, G., STROZZI, F., SYME, R., VOS, R., WENNBLOM, T.J., WOODCROFT, B.J., KATAYAMA, T. & PRINS, P. 2012: Biogem: an effective tool-based approach for scaling up open source software development in bioinformatics. – Bioinformatics 28: 1035-1037.

-

BOURKE, A.F., GREEN, H.A. & BRUFORD, M.W. 1997: Parentage, reproductive skew and queen turnover in a multiple-queen ant analysed with microsatellites. – Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 264: 277-283.

-

BRADNAM, K.R., FASS, J.N., ALEXANDROV, A., BARANAY, P., BECHNER, M., BIROL, I., BOISVERT, S., CHAPMAN, J.A., CHAPUIS, G., CHIKHI, R., CHITSAZ, H., CHOU, W.-C., CORBEIL, J., FABBRO, C. DEL, DOCKING, T.R., DURBIN, R., EARL, D., EMRICH, S., FEDOTOV, P., FONSECA, N.A., GANAPATHY, G., GIBBS, R.A., GNERRE, S., GODZARIDIS, E., GOLDSTEIN, S., HAIMEL, M., HALL, G., HAUSSLER, D., HIATT, J.B., HO, I.Y., HOWARD, J., HUNT, M., JACKMAN, S.D., JAFFE, D.B., JARVIS, E.D., JIANG, H., KAZAKOV, S., KERSEY, P.J., KITZMAN, J.O., KNIGHT, J.R., KOREN, S., LAM, T.-W., LAVENIER, D., LAVIOLETTE, F., LI, Y., LI, Z., LIU, B., LIU, Y., LUO, R., MACCALLUM, I., MACMANES, M.D., MAILLET, N., MELNIKOV, S., NAQUIN, D., NING, Z., OTTO, T.D., PATEN, B., PAULO, O.S., PHILLIPPY, A.M., PINA-MARTINS, F., PLACE, M., PRZYBYLSKI, D., QIN, X., QU, C., RIBEIRO, F.J., RICHARDS, S., ROKHSAR, D.S., RUBY, J.G., SCALABRIN, S., SCHATZ, M.C., SCHWARTZ, D.C., SERGUSHICHEV, A., SHARPE, T., SHAW, T.I., SHENDURE, J., SHI, Y., SIMPSON, J.T., SONG, H., TSAREV, F., VEZZI, F., VICEDOMINI, R., VIEIRA, B.M., WANG, J., WORLEY, K.C., YIN, S., YIU, S.-M., YUAN, J., ZHANG, G., ZHANG, H., ZHOU, S. & KORF, I.F. 2013: Assemblathon 2: evaluating de novo methods of genome assembly in three vertebrate species. – GigaScience 2: 10.

-

BRADY, S.G., SCHULTZ, T.R., FISHER, B.L. & WARD, P.S. 2006: Evaluating alternative hypotheses for the early evolution and diversification of ants. – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103: 18172-18177.

-

BREWER, M.S., COTORAS, D.D., CROUCHER, P.J.P. & GILLESPIE, R.G. 2014: New sequencing technologies, the development of genomics tools, and their applications in evolutionary arachnology. – Journal of Arachnology 42: 1-15.

-

BUTLER, I.A., SILETTI, K., OXLEY, P.R. & KRONAUER, D.J.C. 2014: Conserved microsatellites in ants enable population genetic and colony pedigree studies across a wide range of species. – Public Library of Science One 9: e107334.

-

CHAPUISAT, M., GOUDET, J. & KELLER, L. 1997: Microsatellites reveal high population viscosity and limited dispersal in the ant Formica paralugubris. – Evolution 51: 475-482.

-

CHITTKA, A., WURM, Y. & CHITTKA, L. 2012: Epigenetics: the making of ant castes. – Current Biology 22: R835- R838.

-

CHOI, M.-Y., VANDER MEER, R.K., SHOEMAKER, D. & VALLES, S.M. 2011: PBAN gene architecture and expression in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. – Journal of Insect Physiology 57: 161-165.

-

CHOI, M.-Y., VANDER MEER, R.K., COY, M. & SCHARF, M.E. 2012: Phenotypic impacts of PBAN RNA interference in an ant, Solenopsis invicta, and a moth, Helicoverpa zea. – Journal of Insect Physiology 58: 1159-1165.

-

CROUCH, S., HONG, N.C., HETTRICK, S., JACKSON, M., PAWLIK, A., SUFI, S., CARR, L., DE ROURE, D., GOBLE, C.A. & PARSONS, M. 2013: The software sustainability institute: changing research software attitudes and practices. – Computing in Science and Engineering 15: 74-80.

-

COCK, P.J., ANTAO, T., CHANG, J.T., CHAPMAN, B.A., COX, C.J., DALKE, A., FRIEDBERG, I., HAMELRYCK, T., KAUFF, F., WILCZYNSKI, B. & DE HOON, M.J.L. 2009: Biopython: freely available Python tools for computational molecular biology and bioinformatics. – Bioinformatics 25: 1422-1423.

-

CORONA, M., LIBBRECHT, R., WURM, Y., RIBA-GROGNUZ, O., STUDER, R.A. & KELLER, L. 2013: Vitellogenin underwent subfunctionalization to acquire caste and behavioral specific expression in the harvester ant Pogonomyrmex barbatus. – Public Library of Science Genetics 9: e1003730.

-

DALL’OLIO, G.M., MARINO, J., SCHUBERT, M., KEYS, K.L., STEFAN, M.I., GILLESPIE, C.S., POULAIN, P., SHAMEER, K., SUGAR, R., INVERGO, B.M., JENSEN, L.J., BERTRANPETIT, J. & LAAYOUNI, H. 2011: Ten simple rules for getting help from online scientific communities. – Public Library of Science Computational Biology 7: e1002202.

-

DAVEY, J.W., HOHENLOHE, P.A., ETTER, P.D., BOONE, J.Q., CATCHEN, J.M. & BLAXTER, M.L. 2011: Genome-wide genetic marker discovery and genotyping using next-generation sequencing. – Nature Reviews Genetics 12: 499-510.

-

DAVENPORT, T. H. & PATIL, D. J. 2012: Data scientist. – Harvard Business Review October: 70-76.

-

DENTON, J.F., LUGO-MARTINEZ, J., TUCKER, A.E., SCHRIDER, D.R., WARREN, W.C. & HAHN, M.W. 2014: Extensive error in the number of genes inferred from draft genome assemblies. – Public Library of Science Computational Biology 10: e1003998.

-

DUDLEY, J.T. & BUTTE, A.J. 2009: A quick guide for developing effective bioinformatics programming skills. – Public Library of Science Computational Biology 5: e1000589.

-

EKBLOM, R. & GALINDO, J. 2011: Applications of next generation sequencing in molecular ecology of non-model organisms. – Heredity 107: 1-15.

-

ELLEGREN, H. 2013: The evolutionary genomics of birds. – Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 44: 239-259.

-

ELSIK, C.G., WORLEY, K.C., BENNETT, A.K., BEYE, M., CAMARA, F., CHILDERS, C.P., GRAAF, D.C. DE, DEBYSER, G., DENG, J., DEVREESE, B., ELHAIK, E., EVANS, J.D., FOSTER, L.J., GRAUR, D., GUIGO, R., HOFF, K.J., HOLDER, M.E., HUDSON, M.E., HUNT, G.J., JIANG, H., JOSHI, V., KHETANI, R.S., KOSAREV, P., KOVAR, C.L., MA, J., MALESZKA, R., MORITZ, R.F.A., MUNOZTORRES, M.C., MURPHY, T.D., MUZNY, D.M., NEWSHAM, I.F., REESE, J.T., ROBERTSON, H.M., ROBINSON, G.E., RUEPPELL, O., SOLOVYEV, V., STANKE, M., STOLLE, E., TSURUDA, J.M., VAERENBERGH, M. VAN, WATERHOUSE, R.M., WEAVER, D.B., WHITFIELD, C.W., WU, Y., ZDOBNOV, E.M., ZHANG, L., ZHU, D. & GIBBS, R.A. 2014: Finding the missing honey bee genes: lessons learned from a genome upgrade. – BioMed Central Genomics 15: 86.

-

EMERSON, K.J., MERZ, C.R., CATCHEN, J.M., HOHENLOHE, P.A., CRESKO, W.A., BRADSHAW, W.E. & HOLZAPFEL, C.M. 2010: Resolving postglacial phylogeography using high-throughput sequencing. – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107: 16196-16200.

-

FAIRCLOTH, B.C. 2008: Msatcommander: Detection of microsatellite repeat arrays and automated, locus-specific primer design. – Molecular Ecology Resources 8: 92-94.

-

FANG, Z. & CUI, X. 2011: Design and validation issues in RNAseq experiments. – Briefings in Bioinformatics 12: 280-287.

-

FELDMEYER, B., ELSNER, D. & FOITZIK, S. 2014: Gene expression patterns associated with caste and reproductive status in ants: worker-specific genes are more derived than queen-specific ones. – Molecular Ecology 23: 151-161.

-

FIELD, D., TIWARI, B., BOOTH, T., HOUTEN, S., SWAN, D., BERTRAND, N. & THURSTON, M. 2006: Open software for biologists: from famine to feast. – Nature Biotechnology 24: 801-803.

-

FINSETH, F.R. & HARRISON, R.G. 2014: A comparison of next generation sequencing technologies for transcriptome assembly and utility for RNA-Seq in a non-model bird. – Public Library of Science One 9: e108550.

-

FITZPATRICK, M.J., BEN-SHAHAR, Y., SMID, H.M., VET, L.E.M., ROBINSON, G.E. & SOKOLOWSKI, M.B. 2005: Candidate genes for behavioural ecology. – Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20: 96-104.

-

FLORES, K.B. & AMDAM, G.V. 2011: Deciphering a methylome: what can we read into patterns of DNA methylation? – The Journal of Experimental Biology 214: 3155-3163.

-

FLOT, J.-F., HESPEELS, B., LI, X., NOEL, B., ARKHIPOVA, I., DANCHIN, E.G.J., HEJNOL, A., HENRISSAT,B., KOSZUL,R., AURY, J.-M., BARBE, V., BARTHÉLÉMY, R.-M., BAST, J., BAZYKIN, G.A., CHABROL, O., COULOUX, A., ROCHA, M. DA, SILVA, C. DA, GLADYSHEV, E., GOURET, P., HALLATSCHEK, O., HECOXLEA, B., LABADIE, K., LEJEUNE, B., PISKUREK, O., POULAIN, J., RODRIGUEZ, F., RYAN, J.F., VAKHRUSHEVA, O.A., WAJNBERG, E., WIRTH, B., YUSHENOVA, I., KELLIS, M., KONDRASHOV, A.S., MARK WELCH, D.B., PONTAROTTI, P., WEISSENBACH, J., WINCKER, P., JAILLON, O. & DONINCK, K. VAN 2013: Genomic evidence for ameiotic evolution in the bdelloid rotifer Adineta vaga. – Nature 500: 453-457.

-

GADAGKAR, R. 2011: The birth of ant genomics. – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108: 5477-5478.

-

GADAU, J., HELMKAMPF, M., NYGAARD, S., ROUX, J., SIMOLA, D.F., SMITH, C.R., SUEN, G., WURM, Y. & SMITH, C.D. 2012: The genomic impact of 100 million years of social evolution in seven ant species. – Trends in Genetics 28: 14-21.

-

GARDNER, M.G., FITCH, A.J., BERTOZZI, T. & LOWE, A.J. 2011: Rise of the machines-recommendations for ecologists when using next generation sequencing for microsatellite development. – Molecular Ecology Resources 11: 1093-1101.

-

GENTLEMAN, R.C., CAREY, V.J., BATES, D.M., BOLSTAD, B., DETTLING, M., DUDOIT, S., ELLIS, B., GAUTIER, L., GE, Y., GENTRY, J., HORNIK, K., HOTHORN, T., HUBER, W., IACUS, S., IRIZARRY, R., LEISCH, F., LI, C., MAECHLER, M., ROSSINI, A.J., SAWITZKI, G., SMITH, C., SMYTH, G., TIERNEY, L., YANG, J.Y.H. & ZHANG, J. 2004: Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. – Genome Biology 5: R80.

-

GLASTAD, K.M., HUNT, B.G. & GOODISMAN, M.A. 2014: Evolutionary insights into DNA methylation in insects. – Current Opinion in Insect Science 1: 25-30.

-

GOECKS, J., NEKRUTENKO, A. & TAYLOR, J. 2010: Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. – Genome Biology 11: R86.

-

GÓNGORA-CASTILLO, E. & BUELL, C.R. 2013: Bioinformatics challenges in de novo transcriptome assembly using short read sequences in the absence of a reference genome sequence. – Natural Product Reports 30: 490-500.

-

GOODISMAN, M.A.D., ISOE, J., WHEELER, D.E. & WELLS, M.A. 2005: Evolution of insect metamorphosis: a microarray-based study of larval and adult gene expression in the ant Camponotus festinatus. – Evolution 59: 858-870.

-

GOODISMAN, M.A.D., KOVACS, J.L. & HUNT, B.G.H. 2008: Functional genetics and genomics in ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): The interplay of genes and social life. – Myrmecological News 11: 107-117.

-

GOTO, N., PRINS, P., NAKAO, M., BONNAL, R., AERTS, J. & KATAYAMA, T. 2010: BioRuby: bioinformatics software for the Ruby programming language. – Bioinformatics 26: 2617-2619.

-

GRÄFF, J., JEMIELITY, S., PARKER, J.D., PARKER, K.M. & KELLER, L. 2007: Differential gene expression between adult queens and workers in the ant Lasius niger. – Molecular Ecology 16: 675-683.

-

GROSS, M. 2011: Riding the wave of biological data. – Current Biology 21: R204-R206.

-

GYLLENSTRAND, N.J., GERTSCH, P. & PAMILO, P. 2002: Polymorphic microsatellite DNA markers in the ant Formica exsecta. – Molecular Ecology Notes 2: 67-69.

-

HELMKAMPF, M., CASH, E. & GADAU, J. 2015: Evolution of the insect desaturase gene family with an emphasis on social Hymenoptera. – Molecular Biology and Evolution 32: 456-471.

-

HOHENLOHE, P.A., BASSHAM, S., ETTER, P.D., STIFFLER, N., JOHNSON, E.A. & CRESKO, W.A. 2010: Population genomics of parallel adaptation in threespine stickleback using sequenced RAD tags. – Public Library of Science Genetics 6: e1000862.

-

HOLMAN, L., LANFEAR, R. & D’ETTORRE, P. 2013: The evolution of queen pheromones in the ant genus Lasius. – Journal of Evolutionary Biology 26: 1549-1558.

-

HUNT, B.G., OMETTO, L., WURM, Y., SHOEMAKER, D., YI, S.V. & KELLER, L. 2011: Relaxed selection is a precursor to the evolution of phenotypic plasticity. – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108: 15936-15941.

-

INGRAM, K.K., OEFNER, P. & GORDON, D.M. 2005: Task-specific expression of the foraging gene in harvester ants. – Molecular Ecology 14: 813-818.

-

INGRAM, K.K., KUTOWOI, A., WURM, Y., SHOEMAKER, D., MEIER, R. & BLOCH, G. 2012: The molecular clockwork of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. – Public Library of Science One 7: e45715.

-

JOHNSON, B.R., BOROWIEC, M.L., CHIU, J.C., LEE, E.K., ATALLAH, J. & WARD, P.S. 2013: Phylogenomics resolves evolutionary relationships among ants, bees, and wasps. – Current Biology 23: 2058-2062.

-

JURAN,J.M. 1951: Quality control handbook. 1st edition. – McGrawHill Book Company, NY, pp. 37-41.

-

KIM, K.E., PELUSO, P., BAYBAYAN, P., YEADON, P.J., YU, C., FISHER, W., CHIN, C.S., RAPICAVOLI, N.A., RANK, D.R., LI, J., CATCHESIDE, D., CELNIKER, S.E., PHILLIPPY, A.M., BERGMAN C.M. & LANDOLIN J.M. 2014: Long-read, whole genome shotgun sequence data for five model organisms. – Scientific Data 1: 140045.

-

KOCH, V., NISSEN, I., SCHMITT, B.D. & BEYE, M. 2014: Independent evolutionary origin of fem paralogous genes and complementary sex determination in hymenopteran insects. – Public Library of Science One 9: e91883.

-

KRIEGER, M.J.B. & ROSS, K.G. 2005: Molecular evolutionary analyses of the odorant-binding protein gene Gp-9 in fire ants and other Solenopsis species. – Molecular Biology and Evolution 22: 2090-2103.

-

KULMUNI, J., WURM, Y. & PAMILO, P. 2013: Comparative genomics of chemosensory protein genes reveals rapid evolution and positive selection in ant-specific duplicates. – Heredity 110: 538-547.

-

LEIPZIG, J. 2011: Big-Ass Servers(TM) and the myths of clustersin bioinformatics. – Personal blog: <jermdemo.blogspot.co.uk/2011/06/big-ass-servers-and-myths-of-clusters.html>, retrieved on 28 January 2015.

-

LENOIR, A., D’ETTORRE, P., ERRARD, C. & HEFETZ, A. 2001: Chemical ecology and social parasitism in ants. – Annual Review of Entomology 46: 573-599.

-

LEWIS, J. & LOFTUS, W. 2008: Java software solutions foundations of programming design. 6th edition. – Pearson Education Inc., Boston, MA, 804 pp.

-

LI, J.B. & CHURCH, G.M. 2013: Deciphering the functions and regulation of brain-enriched A-to-I RNA editing. – Nature Neuroscience 16: 1518-1522.

-

LIBBRECHT, R., OXLEY, P.R., KRONAUER, D.J. & KELLER, L. 2013: Ant genomics sheds light on the molecular regulation of social organization. – Genome Biology 14: 212.

-

LOMAN, N. & WATSON, M. 2013: So you want to be a computational biologist? – Nature Biotechnology 31: 996-998.

-

LU, H.-L., VINSON, S.B. & PIETRANTONIO, P.V. 2009: Oocyte membrane localization of vitellogenin receptor coincides with queen flying age, and receptor silencing by RNAi disrupts egg formation in fire ant virgin queens. – FEBS Journal 276: 3110-3123.

-

LUCAS,C. &SOKOLOWSKI, M.B. 2009: Molecular basis for changes in behavioral state in ant social behaviors. – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 106: 6351-6356.

-

LUCAS, C., NICOLAS, M. & KELLER, L. 2015: Expression of foraging and Gp-9 are associated with social organization in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. – Insect Molecular Biology 24: 93-104.

-

MARX, V. 2013a: Next-generation sequencing: The genome jigsaw. – Nature 501: 263-268.

-

MARX, V. 2013b: Biology: The big challenges of big data. – Nature 498: 255-260.

-

MATSUMOTO, Y. 2000: The ruby programming language. – InformIT, http://www.informit.com/articles/article.aspx?p=18225, retrieved on 28 January 20015.

-

MCCORMACK, J.E., HIRD, S.M., ZELLMER, A.J., CARSTENS, B.C. & BRUMFIELD, R.T. 2013: Applications of next-generation sequencing to phylogeography and phylogenetics. – Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 66: 526-538.

-

MCKENZIE, S.K., OXLEY, P.R. & KRONAUER, D.J.C. 2014: Comparative genomics and transcriptomics in ants provide new insights into the evolution and function of odorant binding and chemosensory proteins. – BioMed Central Genomics 15: 718.

-

MIKHEYEV, A.S., VO, T., WEE, B., SINGER, M.C. & PARMESAN, C. 2010: Rapid microsatellite isolation from a butterfly by de novo transcriptome sequencing: performance and a comparison with AFLP-derived distances. – Public Library of Science One 5: e11212.

-

MILLER, G. 2006: A scientist’s nightmare: software problem leads to five retractions. – Science 314: 1856-1857.

-

MIYAZAKI, S., OKADA, Y., MIYAKAWA, H., TOKUDA, G., CORNETTE, R., KOSHIKAWA, S., MAEKAWA, K. & MIURA, T. 2014: Sexually dimorphic body color is regulated by sex-specific expression of yellow gene in ponerine ant, Diacamma sp. – Public Library of Science One 9: e92875.

-

MORANDIN, C., HAVUKAINEN, H., KULMUNI, J., DHAYGUDE, K., TRONTTI, K. & HELANTERÄ, H. 2014: Not only for egg yolkfunctional and evolutionary insights from expression, selection, and structural analyses of Formica ant vitellogenins. – Molecular Biology and Evolution 31: 2181-2193.

-

MOREAU, C.S., BELL, C.D., VILA, R., ARCHIBALD, S.B. & PIERCE, N.E. 2006: Phylogeny of the ants: diversification in the age of angiosperms. – Science 312: 101-104.

-

MUNOZ-TORRES, M.C., REESE, J.T., CHILDERS, C.P., BENNETT, A.K., SUNDARAM,J.P., CHILDS, K.L., ANZOLA,J.M., MILSHINA, N. & ELSIK, C.G. 2011: Hymenoptera genome database: integrated community resources for insect species of the order Hymenoptera. – Nucleic Acids Research 39: D658-D662.

-

NARUM, S.R., BUERKLE, C.A., DAVEY, J.W., MILLER, M.R. & HOHENLOHE, P.A. 2013: Genotyping-by-sequencing in ecological and conservation genomics. – Molecular Ecology 22: 2841-2847.

-

NATURE CELL BIOLOGY EDITORS 2012: The data deluge. – Nature Cell Biology 14: 775.

-

NYGAARD, S., ZHANG, G., SCHIØTT, M., LI, C., WURM, Y., HU, H., ZHOU, J., JI, L., QIU, F., RASMUSSEN, M., PAN, H., HAUSER, F., KROGH, A., GRIMMELIKHUIJZEN, C.J.P., WANG, J. & BOOMSMA, J.J. 2011: The genome of the leaf-cutting ant Acromyrmex echinatior suggests key adaptations to advanced social life and fungus farming. – Genome Research 21: 1339-1348.

-

NYSTEDT, B., STREET, N.R., WETTERBOM, A., ZUCCOLO, A., LIN, Y.-C., SCOFIELD, D.G., VEZZI, F., DELHOMME, N., GIACOMELLO, S., ALEXEYENKO, A., VICEDOMINI, R., SAHLIN, K., SHERWOOD, E., ELFSTRAND, M., GRAMZOW, L., HOLMBERG, K., HÄLLMAN, J., KEECH, O., KLASSON, L., KORIABINE, M., KUCUKOGLU, M., KÄLLER, M., LUTHMAN, J., LYSHOLM, F., NIITTYLÄ, T., OLSON, A., RILAKOVIC, N., RITLAND, C., ROSSELLÓ, J.A., SENA, J., SVENSSON, T., TALAVERA-LÓPEZ, C., THEISSEN, G., TUOMINEN, H., VANNESTE, K., WU, Z.-Q., ZHANG, B., ZERBE, P., ARVESTAD, L., BHALERAO, R., BOHLMANN, J., BOUSQUET, J., GARCIA GIL, R., HVIDSTEN, T.R., JONG, P. DE, MACKAY, J., MORGANTE, M., RITLAND, K., SUNDBERG, B., THOMPSON, S.L., PEER, Y. VAN DE, ANDERSSON, B., NILSSON, O., INGVARSSON, P.K., LUNDEBERG, J. & JANSSON, S. 2013: The Norway spruce genome sequence and conifer genome evolution. – Nature 497: 579-584.

-

OXLEY, P.R., JI, L., FETTER-PRUNEDA, I., MCKENZIE, S.K., LI, C., HU, H., ZHANG, G. & KRONAUER, D.J.C. 2014: The genome of the clonal raider ant Cerapachys biroi. – Current Biology 24: 451-458.

-

OYSTAEYEN, A. VAN, OLIVEIRA, R.C., HOLMAN, L., ZWEDEN, J.S. VAN, ROMERO, C., OI, C.A., D’ETTORRE, P., KHALESI, M., BILLEN, J., WÄCKERS, F., MILLAR, J.G. & WENSELEERS, T. 2014: Conserved class of queen pheromones stops social insect workers from reproducing. – Science 343: 287-290.

-

PAMILO, P., GERTSCH, P., THOREN, P. & SEPPA, P. 1997: Molecular population genetics of social insects. – Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 28: 1-25.

-

PARK, P.J. 2009: ChIP-seq: advantages and challenges of a maturing technology. – Nature Reviews Genetics 10: 669-680.

-

PETTY, N.K. 2010: Genome annotation: man versus machine. – Nature Reviews Microbiology 8: 762.

-

PIWOWAR, H.A. & VISION, T.J. 2013: Data reuse and the open data citation advantage. – PeerJ 1: e175.

-

PRIVMAN, E., WURM, Y. & KELLER, L. 2013: Duplication and concerted evolution in a master sex determiner under balancing selection – Proceedings of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 280: 20122968.

-

PURCELL, J., BRELSFORD, A., WURM, Y., PERRIN, N., CHAPUISAT, M. 2014: Convergent genetic architecture underlies social organization in ants. – Current Biology 24: 2728-2732. RAN, F.A., HSU, P.D., WRIGHT, J., AGARWALA, V., SCOTT, D.A. & ZHANG, F. 2013: Genome engineering using the CRISPRCas9 system. – Nature Protocols 8: 2281-2308.

-

R CORE TEAM 2014: R: A language and environment for statistical computing. – R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://www.r-project.org/, retrieved on 28 January 20015.

-

RHEE, S.Y., WOOD, V., DOLINSKI, K. & DRAGHICI, S. 2008: Use and misuse of the gene ontology annotations. – Nature Reviews Genetics 9: 509-515.

-

ROSS, K.G. & KELLER, L. 1998: Genetic control of social organization in an ant. – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95: 14232-14237.

-

ROUX, J., PRIVMAN, E., MORETTI, S., DAUB, J.T., ROBINSONRECHAVI, M. & KELLER, L. 2014: Patterns of positive selection in seven ant genomes. – Molecular Biology and Evolution 31: 1661-1685.

-

SALZBERG, S.L., PHILLIPPY, A.M., ZIMIN, A., PUIU, D., MAGOC, T., KOREN, S., TREANGEN, T.J., SCHATZ, M.C., DELCHER, A.L., ROBERTS, M., MARC, G., POP, M. & YORKE, J.A. 2012: GAGE : A critical evaluation of genome assemblies and assembly algorithms. – Genome Research 22: 557-567.

-

SBONER, A., MU, X.J., GREENBAUM, D., AUERBACH, R.K. & GERSTEIN, M.B. 2011: The real cost of sequencing: higher than you think! – Genome Biology 12: 125.

-

SCHATZ, M.C. 2012: Computational thinking in the era of big data biology. – Genome Biology 13: 177.

-

SCHRADER, L., KIM, J., ENCE, D., ZIMIN, A., KLEIN, A., WYSCHETZKI, K., WEICHSELGARTNER, T., KEMENA, C., STÖKL, J., SCHULTNER, E., WURM, Y., SMITH, C.D, YANDELL, M., HEINZE, J., GADAU, J. & OETTLER, J. 2014: Transposable element islands facilitate adaptation to novel environments in an invasive species. – Nature Communications 5: 5495.

-

SCHULTZ, T.R. & BRADY, S.G. 2008: Major evolutionary transitions in ant agriculture. – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105: 5435-5440.

-

SCOTT, J.G., MICHEL, K., BARTHOLOMAY, L.C., SIEGFRIED, B.D., HUNTER, W.B., SMAGGHE, G., ZHU, K.Y. & DOUGLAS, A.E. 2013: Towards the elements of successful insect RNAi. – Journal of Insect Physiology 59: 1212-1221.

-

SEARLS, D.B. 2012: An online bioinformatics curriculum. – Public Library of Science Computational Biology 8: e1002632.

-

SIMOLA, D.F., WISSLER, L., DONAHUE, G., WATERHOUSE, R.M., HELMKAMPF, M., ROUX, J., NYGAARD, S., GLASTAD, K.M., HAGEN, D.E., VILJAKAINEN, L., REESE,J.T., HUNT, B.G., GRAUR, D., ELHAIK, E., KRIVENTSEVA, E.V., WEN, J., PARKER, B.J., CASH, E., PRIVMAN, E., CHILDERS, C.P., MUÑOZ-TORRES, M.C., BOOMSMA, J.J., BORNBERG-BAUER, E., CURRIE, C.R., ELSIK, C.G., SUEN, G., GOODISMAN, M.A.D., KELLER, L., LIEBIG, J., RAWLS, A., REINBERG, D., SMITH, C.D., SMITH, C.R., TSUTSUI, N., WURM, Y., ZDOBNOV, E.M., BERGER, S.L. & GADAU, J. 2013a: Social insect genomes exhibit dramatic evolution in gene composition and regulation while preserving regulatory features linked to sociality. – Genome Research 23: 1235-1247.

-

SIMOLA, D.F., YE, C., MUTTI, N.S., DOLEZAL, K., BONASIO, R., LIEBIG, J., REINBERG, D. & BERGER, S.L. 2013b: A chromatin link to caste identity in the carpenter ant Camponotus floridanus. – Genome Research 23: 486-496.

-

SMITH, C.D., ZIMIN, A., HOLT, C., ABOUHEIF, E., BENTON, R., CASH, E., CROSET, V., CURRIE, C.R., ELHAIK, E., ELSIK, C.G., FAVE, M.-J., FERNANDES, V., GADAU, J., GIBSON, J.D., GRAUR, D., GRUBBS, K.J., HAGEN, D.E., HELMKAMPF, M., HOLLEY, J.- A., HU, H., VINIEGRA, A.S.I., JOHNSON, B.R., JOHNSON, R.M., KHILA, A., KIM, J.W., LAIRD, J., MATHIS, K.A., MOELLER, J.A., MUÑOZ-TORRES, M.C., MURPHY, M.C., NAKAMURA, R., NIGAM, S., OVERSON, R.P., PLACEK, J.E., RAJAKUMAR, R., REESE, J.T., ROBERTSON, H.M., SMITH, C.R., SUAREZ, A.V., SUEN, G., SUHR, E.L., TAO, S., TORRES, C.W., WILGENBURG, E. VAN, VILJAKAINEN, L., WALDEN, K.K.O., WILD, A.L., YANDELL, M., YORKE, J.A. & TSUTSUI, N.D. 2011: Draft genome of the globally widespread and invasive Argentine ant (Linepithema humile). – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108: 5673-5678.

-

SMITH, C.R., SMITH, C.D., ROBERTSON, H.M., HELMKAMPF, M., ZIMIN, A., YANDELL, M., HOLT, C., HU, H., ABOUHEIF, E., BENTON, R., CASH, E., CROSET, V., CURRIE, C.R., ELHAIK, E., ELSIK, C.G., FAVÉ, M.-J., FERNANDES, V., GIBSON,J.D., GRAUR, D., GRONENBERG, W., GRUBBS, K.J., HAGEN, D.E., VINIEGRA, A.S.I., JOHNSON, B.R., JOHNSON, R.M., KHILA, A., KIM, J.W., MATHIS, K.A., MUNOZ-TORRES, M.C., MURPHY, M.C., MUSTARD, J.A., NAKAMURA, R., NIEHUIS, O., NIGAM, S., OVERSON, R.P., PLACEK, J.E., RAJAKUMAR, R., REESE, J.T., SUEN, G., TAO, S., TORRES, C.W., TSUTSUI, N.D., VILJAKAINEN, L., WOLSCHIN, F. & GADAU, J. 2011: Draft genome of the red harvester ant Pogonomyrmex barbatus. – Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108: 5667-5672.

-

STAJICH, J.E., BLOCK, D., BOULEZ, K., BRENNER, S.E., CHERVITZ, S.A., DAGDIGIAN, C., FUELLEN, G., GILBERT, J.G.R., KORF, I., LAPP, H., LEHVÄSLAIHO, H., MATSALLA, C., MUNGALL, C.J., OSBORNE, B.I., POCOCK, M.R., SCHATTNER, P., SENGER, M., STEIN, L.D., STUPKA, E., WILKINSON, M.D. & BIRNEY, E. 2002: The Bioperl toolkit: Perl modules for the life sciences. – Genome Research 12: 1611-1618.

-

STAPLEY, J., REGER, J., FEULNER, P.G.D., SMADJA, C., GALINDO, J., EKBLOM, R., BENNISON, C., BALL, A.D., BECKERMAN, A.P. & SLATE, J. 2010: Adaptation genomics: the next generation. – Trends in Ecology & Evolution 25: 705-712.

-

STEIN, L.D. 2010: The case for cloud computing in genome informatics. – Genome Biology 11: 207. STEMPLE, D.L. 2013: So, you want to sequence a genome … – Genome Biology 14: 128.

-

STOLLE, E. & MORITZ, R.F.A. 2013: RESTseq – efficient benchtop population genomics with RESTriction Fragment SEQuencing. – Public Library of Science One 8: e63960.

-