Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 30 September 2013

Discovery and molecular characterization of an ambisense densovirus from South American populations of Solenopsis invicta

S. Valles, D. Shoemaker, Y. Wurm, C. Strong, L. Varone, J. Becnel, P. Shirk

Biological Control, 2013, 67:431-39

Abstract

In an effort to discover viruses as classical biological control agents, a metatranscriptomics/pyrosequencing approach was used to survey native Solenopsis invicta collected exclusively in Argentina. A new virus was discovered with characteristics consistent with the family Parvoviridae, subfamily Densovirinae. The virus, tentatively named Solenopsis invicta densovirus (SiDNV), represents the first DNA virus discovered in ants (Formicidae) and the first densovirus in a hymenopteran insect. The ambisense genome was 5280 nucleotides in length and the termini possessed asymmetrically positioned inverted terminal repeats, formed hairpin loops, and had transcriptional regulatory elements including CAAT and TATA sites. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that SiDNV belongs to a group that includes two other densoviruses found in insects (Acheta domestica densovirus and Planococcus citri densovirus). SiDNV was prevalent in fire ants from Argentina but completely absent in fire ants found in the USA indicating that this virus has potential for biological control of introduced S. invicta.

1. Introduction

The red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta (Buren) was introduced into the United States sometime between 1933 and 1945 (Tschinkel, 2006) from Argentina (Caldera et al., 2008). This invasive ant species currently infests more than 138 million hectares from North Carolina to California (Callcott and Collins, 1996). Comparative analyses of populations on the two continents (introduced versus native) provide strong evidence that S. invicta escaped its natural enemies during the USA colonization; fire ant populations are greater in number (5-fold), found in higher densities (5.7-fold), possess larger mound volumes (2-fold), and comprise a larger fraction of the ant community (7.5-fold) in infested areas within the USA (Porter et al., 1992, 1997). These observations are further supported by the paucity of natural enemies found in introduced (USA) populations of S. invicta. While S. invicta serves as host to more than 21 parasites in the native range (Schmid-Hempel, 1998) only a fraction of these are found in fire ants in the USA. Currently, two species of endoparasitic fungi (Jouvenaz and Kimbrough, 1991; Pereira, 2004), a microsporidian obligate parasite (Knell and Allen, 1977; Williams et al., 1998), a neogregarine parasite (Pereira et al., 2002), a strepsipteran parasite (Kathirithamby and Johnston, 2001), three positive strand RNA viruses (Valles and Hashimoto, 2009; Valles et al., 2004, 2007), and five phorid flies in the genus Pseudacteon (Porter, 1998), which were intentionally introduced, comprise the known self-sustaining, parasites/pathogens in USA populations of S. invicta. Thus, discovery, importation and introduction of additional biological control agents from South American populations of S. invicta continue to be emphasized by many research laboratories in the USA (Williams et al., 2003).

Although viruses can be important biological control agents against insect populations (Lacey et al., 2001), none were known to exist in fire ants until a metagenomics approach was employed (Valles et al., 2008). Three positive strand RNA viruses have been discovered and characterized in fire ants previously using this approach: Solenopsis invicta virus 1 (SINV-1) (Valles et al., 2004), SINV-2 (Valles et al., 2007), and SINV-3 (Valles and Hashimoto, 2009). All of these viruses are found currently in USA populations of fire ants and are being evaluated primarily for use as biopesticides (Valles et al., 2013).

We employed a metatranscriptomics/pyrosequencing approach to examine S. invicta colonies collected exclusively from Argentina to identify additional viruses for potential use as classical biological control agents of North American S. invicta. A new virus with characteristics consistent with the subfamily Densovirinae (within the family Parvoviridae) was identified (Tijssen et al., 2012). The virus, tentatively named Solenopsis invicta densovirus (SiDNV), represents the first DNA virus discovered in the Formicidae and the first densovirus observed in the Hymenoptera. Molecularbased surveys for SiDNV in both introduced (USA) and native (Argentina) fire ant populations show that this virus is limited to native populations of S. invicta and, as such, may serve as a potential classical biological agent in the USA.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Insects

S. invicta colonies or samples of colonies were collected from various locations in northern Argentina from 2005 through 2008. Sampling was conducted by plunging a vial into the nest mound and collecting worker ants falling into the vial. Ants were either tested immediately for the presence of SiDNV or preserved in 95% ethanol for retrospective evaluation. Ant identifications were based on the key of Trager (1991).

2.2. Library creation and pyrosequencing

Twenty-four nests of S. invicta were collected from various locations in northern Argentina and returned to the laboratory. Samples of ants representing various life stages and castes were collected from each nest and pooled into a single tube. This pooled sample was used as starting material to generate a single normalized cDNA library. RNA was extracted in Tri-reagent (Ambion, Carlsbad, CA) and the quality of total RNA was verified on 1.4% agarose–MOPS–formaldehyde denaturing gel. Poly-A RNA was extracted from the total RNA sample using the Oligotex mRNA Midi Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and the quality again verified on a denaturing gel. This pooled mRNA sample was the source of starting material for the creation of the normalized cDNA library. An initial cDNA library was constructed using the SMART cDNA Synthesis Kit (BD Clonetech, Mountain View, CA) and normalized using the Trimmer-Direct Kit (Evrogen, Moscow). The quality of the normalized cDNA library was verified on a 1.4% agarose gel.

Approximately 2.5 μg of the normalized cDNA pool was used for a titration run using one quarter of a plate on the Roche GS FLX sequencer and was followed by a ½-plate run on the same equipment using the same cDNA at the Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research at the University of Florida (UF-ICBR).

The obtained pyrosequences were assembled using Roche Newbler 1.1.02.15 using default parameters. The resulting assembled sequences were compared to viral genome sequences in the EMBL databank (Release 96, 2008) using BLASTX. SIB BLAST Network Service based on Paracel BLAST (1.5.4) was employed and we retained only the ten strongest hits per assembled sequence. BLAST Output was converted into human-readable tables using custom Ruby/Bioruby scripts. One of the assembled sequences, contig 139, had high similarity to densoviruses found in other insects and was thus chosen for further study.

2.3. Virus detection, purification, and electron microscopy

DNA extracted from S. invicta was evaluated for the presence of SiDNV by PCR with the oligonucleotide primers p866 and p867 (Table 1). The reaction was conducted in a 25 °l volume containing 2 μM MgCl2, 200 lM dNTP mix, 0.5 units of platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen), 0.2 μM of each oligonucleotide primer, and 10–50 ng of DNA template. Amplification was completed in a thermal cycler under the following temperature regime: 1 cycle at 94 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 58 °C for 15 s, 68 °C for 30 s, followed by an elongation step of 68 °C for 5 min. PCR products were separated on a 1% agarose gel and visualized with SYBR-safe dye (Invitrogen).

SiDNV was purified from infected ants on a discontinuous CsCl gradient as described previously (Ghosh et al., 1999). Briefly, SiDNV-infected S. invicta (5 g) preserved in 95% ethanol were blotted dry with a paper towel and then homogenized in 5 ml of NT buffer (Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 10 mM NaCl) using a Potter–Elvehjem Teflon pestle and glass mortar. The mixture was clarified by centrifugation at 1000g for 10 min in an L8-70M ultracentrifuge (Beckman, Palo Alto, CA). The supernatant was extracted with an equal volume of chloroform before the aqueous phase was layered onto a discontinuous CsCl gradient (1.2 and 1.5 g/ml) which was centrifuged at 194,000g for 2 h in a Ti50.2 rotor. A whitish band visible near the interface was removed by suction and desalted. A 5 μl drop of purified viral suspension was applied to a formvar coated grid for approximately 5 min and the excess liquid was removed. The sample was negatively stained by applying a 5 μl drop of a 2% (w/v) aqueous phosphotungstic acid (adjusted to pH 7.5 with 1 N NaOH) solution to the grid for 1 min. Excess liquid was removed and the grid was air dried prior to viewing. The negatively stained specimens were examined and photographed with a Hitachi H-600 transmission electron microscope (Hitachi, Pleasanton, CA) at an accelerating voltage of 75 kV.

2.4. Genome acquisition and characterization

Genomic DNA from SiDNV-infected ant colonies was purified by placing 10 worker ants into a 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube containing 150 μl of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8, 4% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 5% 2-mercaptoethanol). The insects were homogenized with a disposable plastic pestle for 15 s followed by the addition of 200 μl of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol (Tris–HCl-saturated, pH 8). The mixture was inverted 5 times and centrifuged at room temperature for 5 min at 16,000g. The supernatant was removed and nucleic acids precipitated with isopropanol. The pellets were washed with 70% ethanol and dissolved in 30 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8).

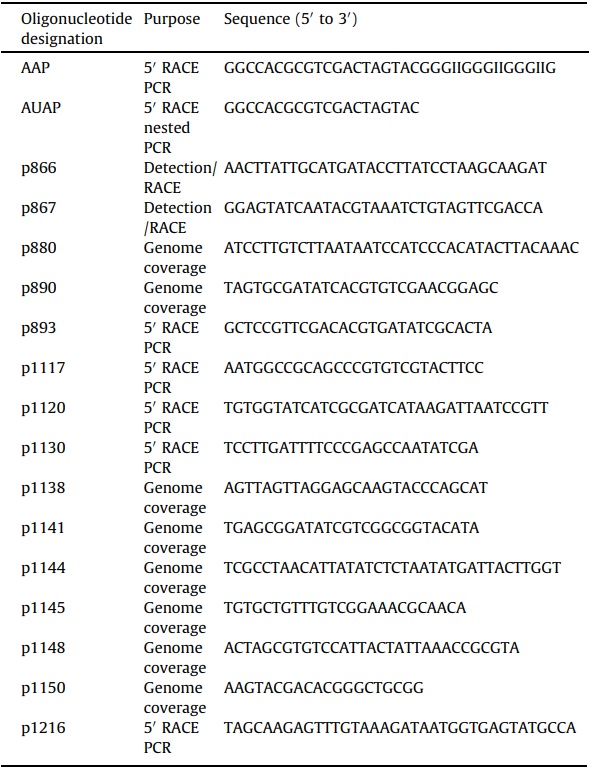

Table 1 – Oligonucleotide primers used in the study.

The virus genome was assembled from sequences acquired by a combination of modified 5’ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) reactions (i.e., anchored PCR (Loh et al., 1989)) and those derived from pyrosequencing. Densoviruses contain single stranded DNA genomes; both positive and negative strand genome sequences may be packaged. Thus, the genome was amenable to anchored PCR (Loh et al., 1989). A 709 nucleotide sequence fragment (contig 139) from pyrosequencing assembly served as the anchor sequence from which the genome was acquired (Fig. 1A). Genomic DNA from SiDNV-infected ants was polycytidylated with terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (Invitrogen) in the presence of 2 mM dCTP. PCR was subsequently conducted with the polycytidylated DNA as template, an SiDNV-specific oligonucleotide primer and the abridged anchor primer (Table 1). Because both sense and antisense genomes were present, forward and reverse SiDNV-specific oligonucleotide primers designed to an established region of the genome and an abridged anchor primer were used in two separate reactions with the following temperature regime: 94 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s, 58 °C for 15 s, 68 °C for 4 min and a final elongation step of 5 min. Gel-purified amplicons were ligated into the pCR4-TOPO vector, transformed into TOP10 competent cells (Invitrogen) and sequenced by the Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research (University of Florida) by the Sanger method.

After each round of 5’ RACE that yielded additional sequence, revised genome assemblies were compared against both the assembled transcriptome library and the unassembled pyrosequencing reads using BLASTN and TBLASTX. These methods were alternated until a putatively complete genome sequence was acquired (Fig. 1A summarizes the assembly process). Once a draft of the genome was acquired, continuous, overlapping regions of the genome were amplified (Table 1), cloned and sequenced to yield a minimum 4-fold coverage.

Folding patterns assumed by the palindromic ITR sections were completed with Mfold software (Zuker, 2003). The overlapping regions were identified manually and these truncated sequences were used to evaluate folding. Sequences were examined for identity by BLASTP analysis (Altschul et al., 1997).

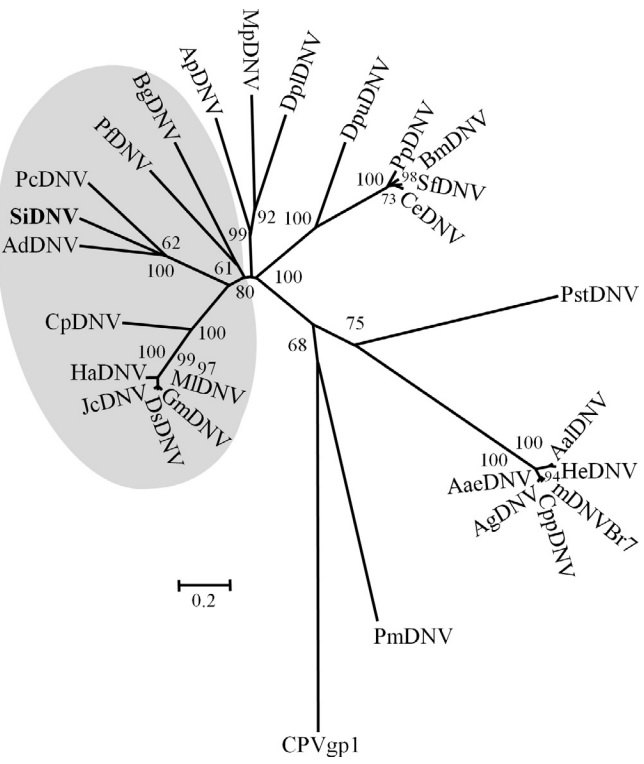

2.5. Phylogenetic analysis

Putative amino acid sequences for NS1 of densoviruses were retrieved from NCBI and aligned with ClustalW (Thompson et al., 1994). A phylogenetic tree based on this alignment was constructed with the Neighbor-Joining method using the MEGA5 program (Tamura et al., 2011). Phylogenetic relationships were displayed as an unrooted radial phylogenetic tree. The statistical significance of branch order was estimated by performing 1000 replications of bootstrap re-sampling of the original aligned amino acid sequences.

2.6. Molecular-based surveys for SiDNV

S. invicta colonies were sampled and tested for the presence of SiDNV in the source (northern Argentina) and introduced (USA) populations by PCR as above with oligonucleotide primers p866 and p867. DNA was prepared from 10 worker ants and used as template in the PCR reaction. Colony-specific information, including location and collection date, is summarized in Table 2.

3. Results

3.1. Genome sequence acquisition and characterization

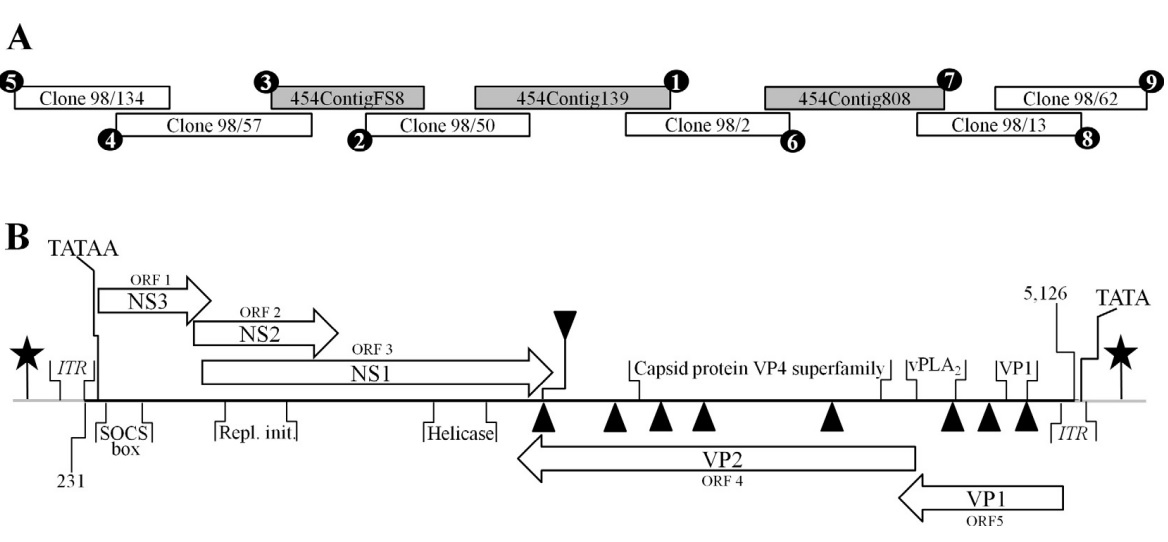

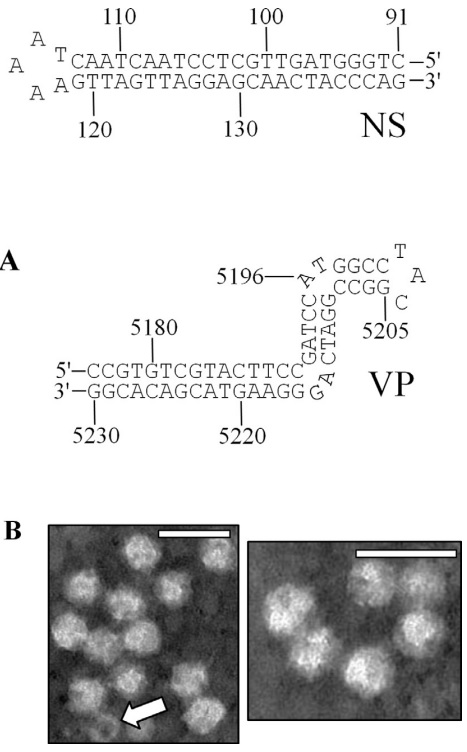

BLAST analyses revealed an assembled contig (contig 139, a 709 nucleotide sequence), generated from pyrosequencing a cDNA library (Genbank accession SRX023380, SRX023381) created from numerous individuals representing South American S. invicta, exhibited significant identity (E-value: 1e–19 to 1e–12) to VP4 of the Planococcus citri densovirus (PcDNV) and Periplaneta fuliginosa densovirus (PfDNV). Using this 709 nt sequence as a starting point, a combination of anchored PCR (Loh et al., 1989) and subsequent assembly procedures stemming from the original pyrosequencing reads were employed to acquire the complete genome sequence of this potential virus (Fig. 1A). Six clones and three pyrosequencing contigs ultimately were assembled to yield the entire genome. Subsequently, multiple overlapping PCR reactions provided 4–5-fold coverage of the genome. Using the naming convention established by the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) (Tijssen et al., 2012), the virus has been tentatively named, Solenopsis invicta densovirus (SiDNV). The SiDNV genome was 5280 nucleotides in length (GenBank accession number KC991097). The A/T rich genome was comprised of 19.2% C, 20.3% G, 30.4% A, and 30.1% T consistent with several viruses in the Densovirinae (Fédière et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2005). By convention, the sequence encoding the putative nonstructural proteins was designated the positive strand; all features were assigned in reference to nt 1 of the 5’ end of the positive strand and the genome is presented with the non-structural (NS) ORFs on the left (Fig. 1B). Similar to other densoviruses, each end of the SiDNV genome contained a hairpin loop and an inverted terminal repeat (ITR) (Figs. 1B and 2A). The 134 nt ITRs were asymmetrically positioned at the 5’ ends and were a large component of the hairpin foldback sequences. The NS ITR was located from nts 105–238. The ITR of the 3’ (VP) end was positioned more internal at nts 5004–5137, which was located slightly towards the 5’ end of the foldback sequence of the hairpin loop. The NS foldback loop was 231 nts in length and formed a simple, compact hairpin structure at nts 114–117 (Fig. 2A). The Gibbs free energy estimate (ΔG) of the foldback structure was 241 with a Tm of 81 °C. The foldback corresponding to the 3’ end was 155 nt in length forming an inverted ‘‘J’’ -shaped hairpin (ΔG = -94; Tm 78 °C).

Fig. 1.

(A) Depiction of the strategy used to acquire the SiDNV genome and components comprising the assembly. 50 RACE (anchored PCR) was conducted to extend the positive and negative strands of the genome. After additional sequence was acquired by this method, subsequent assembly attempts were conducted with pyrosequencing results to further extend the genome sequence. Circled numbers indicate the chronology of each component of the assembly. (B) SiDNV genome organization and components. The solid, horizontal line represents the genome. Grey lines at each terminus represent the feedback loops. ITR regions are identified at each terminus. Putative protein encoding regions are represented by blocked arrows; those facing right correspond to the positive strand and those facing left the negative strand. Stars represent the CAAT boxes and TATA box positions are shown. Triangles represent polyadenylation signals (downward pointing are for the positive strand, upward are for the negative strand). Conserved domains recognized are shown: SOCS box = suppressor of cytokine signaling; Repl. init. = replication initiators; helicase; capsid protein VP4 superfamily; vPLA2 = viral phospholipase A2; VP1 = structural protein 1.

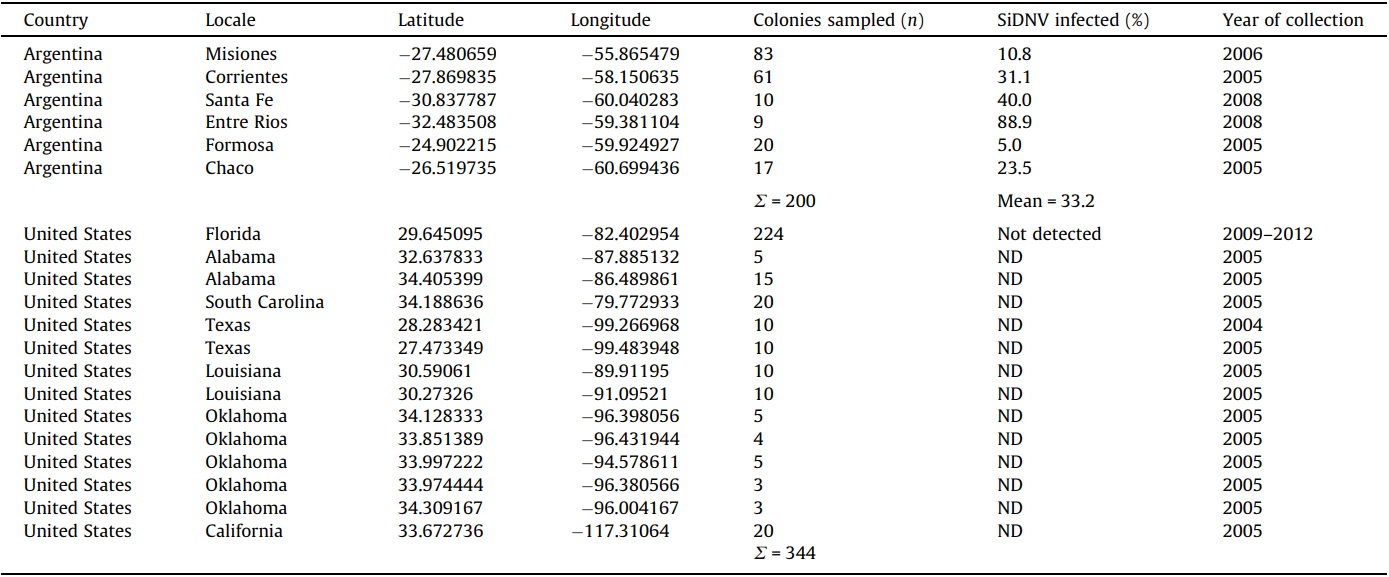

Table 2 – Evaluations for the presence of SiDNV infections in Solenopsis invicta fire ant colonies across northern Argentina and the United States.

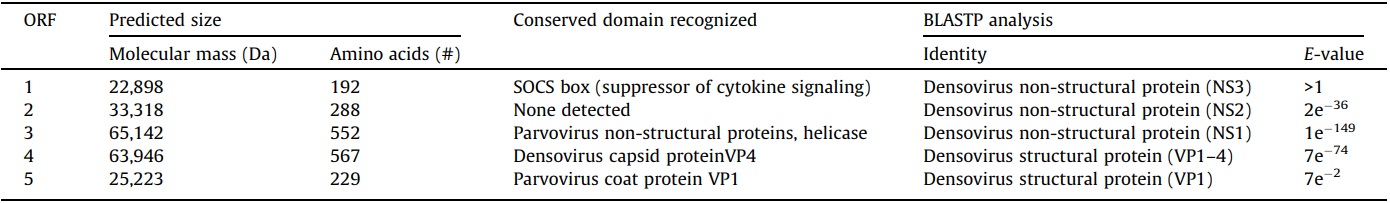

3.2. Predicted coding domains

Five large ORFs were predicted in the SiDNV genome (Fig. 1B). The ORFs were grouped on the 5’ ends of the positive and negative strands. BLASTP analyses revealed the predicted coding sequences of ORFs 1, 2 and 3 on the positive strand shared identity with non-structural (replicative) proteins of viruses in the Densovirinae (Table 3) and ORFs 4 and 5 on the negative strand shared identity with structural (viral capsid) proteins, also in the Densovirinae. This ambisense arrangement is characteristic of all viruses in the Pefudensvirus and Densovirus genera (Bergoin and Tijssen, 2000).

3.3. Non-structural ORFs

Despite poor significance (E-value >1), ORF 1 encoded a predicted protein that was similar to non-structural proteins (NS3) from the Acheta domestica densovirus (AdDNV) (Table 3). A conserved domain for suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS box) was recognized at the N-terminus. ORF 2 encoded predicted proteins that shared high similarity with AdDNV non-structural proteins (NS2), but no conserved domains were recognized. ORF 3 encoded predicted protein that shared high similarity with densovirus non-structural proteins (NS1). A conserved domain was also recognized in the ORF 3 coding sequence for a viral helicase (amino acid [aa] 350–400).

Fig. 2.

(A) Depictions of the terminal NS- (left) and VP- (right) proximal hairpin structures of the SiDNV genome. Only the terminal regions of the feedback loop are represented. (B) Electron micrographs of virions from negative stained specimens of SiDNV. Reference size bar is 50 nm. Arrow indicates an empty capsid.

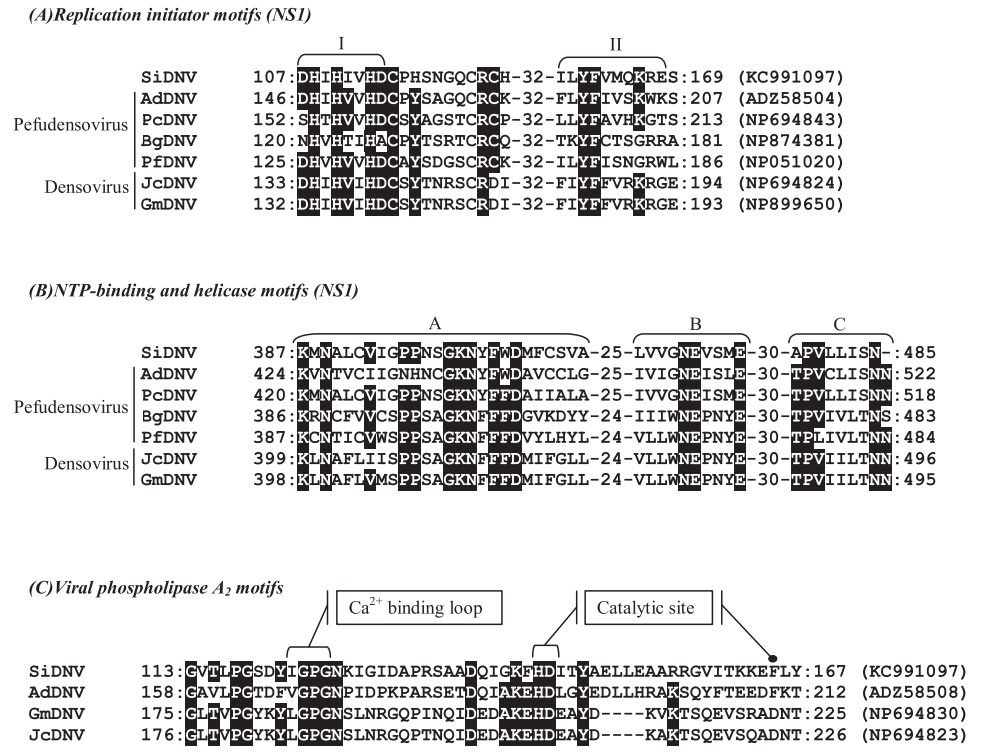

Sequence comparisons with other NS1 densovirus coding regions revealed that SiDNV NS1 (ORF 3) contained conserved sequences corresponding to functional domains for replication initiation (Fig. 3A) and the DNA-dependent ATPase/helicase (aa 387–485) which has been hypothesized to be involved in initiation of DNA replication (Koonin, 1993; Nuesch et al., 1995). The first replication initiation motif (Fig. 3A, I) located at position 107– 114 (aa) contained two conserved histidine residues (H108 and H110) which are thought to function as ligands for metal binding in densovirus replication (Koonin, 1993). The second motif (Fig. 3A, II) located at position 158–168 (aa) contained a conserved tyrosine residue (position 160) which has been shown in the minute virus of mice (MVM) to participate in the cleavage-ligation reaction (Nuesch et al., 1995). These two contiguous regions have been predicted to be involved in initiation and termination of the rolling hairpin replication mechanism characteristic of the Parvoviridae (Berns, 1990; Tijssen et al., 2012).

3.4. Structural ORFs

Predicted proteins within ORFs 4 and 5 shared high similarity with densoviral structural proteins, VP1–VP4 (Table 3). A conserved domain for viral phospholipase A2 (vPLA2) was identified at the carboxyl terminus of ORF 5 (Figs. 1B and 3C). Specifically, the calcium binding loop (aa 122–125) and catalytic sites (aa 144/145 and 165) of the enzyme were recognized (Fig. 3C). The vPLA2 is involved in the trafficking/release of the densoviral genome from late endosomes to the nucleus to initiate replication (Zádori et al., 2001).

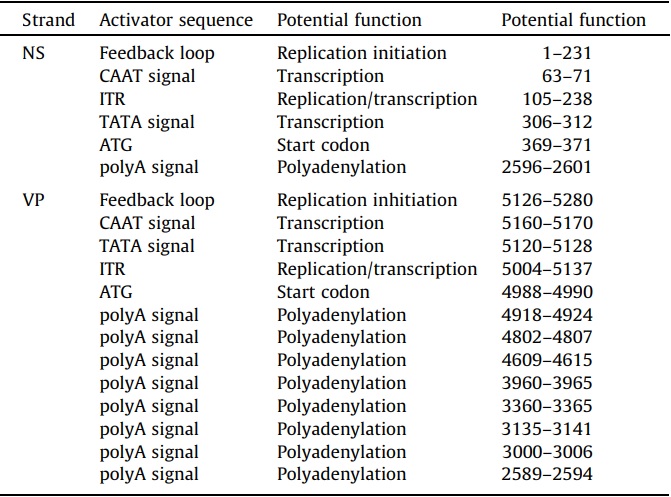

3.5. Possible regulatory sequences

Consensus CAAT and TATA boxes were identified in the 5’ regions of both strands and upstream of the coding sequences (Fig. 1B, Table 4). On the positive strand, a consensus CAAT box (7/9 nts) was a component of the foldback sequence and 235 nts upstream of the consensus TATA box (7/7 nts). The TATA box was outside of the foldback and 57 nts upstream of the 1st codon. A polyadenylation site was identified at nt 2596 which did not correspond to the end of the complete coding sequence for NS1 which was at nt 2670. The transcriptional start sites and polyadenylation sites for transcripts were predicted and not determined empirically. On the negative strand, the consensus CAAT box (7/9 nts) was also a component of the foldback but positioned only 32 nts upstream of the consensus TATA box (5/7 nts). The negative strand TATA box was also outside the foldback and 130 nts upstream of the first codon. There were 8 polyadenylation sites in the coding sequences of the negative strand with only one positioned at 2594, which was downstream of the last stop codon of VP2 (nt 2616).

3.6. Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis of NS1 sequences were conducted using the corresponding predicted proteins from known members comprising the Densovirinae (Fig. 4). SiDNV belongs to a well supported clade that includes two other densoviruses, AdDNV and PcDNV. These viruses (AdDNV and PcDNV) are proposed new species of the Pefudensovirus genus, which has not been adopted officially by the ICTV (Tijssen et al., 2012). However, our analysis suggests that the NS1 sequences of these three viruses are more closely related to those from densoviruses and likely warrant placement within a genus separate from Pefudensovirus. The analysis supports the previously hypothesized single evolutionary origin of the ambisense genome structure within the Densovirinae.

3.7. Field surveys

Molecular-based assays for SiDNV revealed that this virus appears to be limited to S. invicta populations in South America and is absent in USA populations. The prevalence of SiDNV infections ranged from 5% to 88.9% among six sampled populations (n = 200 colonies) across northern Argentina, the area considered to be the source for the USA introduction (Caldera et al., 2008) (Table 2). The overall proportion of SiDNV-infected S. invicta colonies in Argentina was 33.2%. In contrast, none of the 344 S. invicta colonies sampled from across the range of S. invicta in the USA were infected with SiDNV.

Table 3 – Characteristics of each SiDNV predicted ORF product, conserved domains, and gene identities recognized by BLASTP analysis.

Fig. 3.

Alignment comparisons of predicted amino acid sequences of NS1 (A and B) and VP1 (C) of Solenopsis invicta DNV (SiDNV), Acheta domestica DNV (AdDNV), Planococcus citri DNV (PcDNV), Blattella germanica DNV (BgDNV), Periplaneta fuliginosa DNV (PfDNV), Junonia coenia DNV (JcDNV), and Galleria mellonella DNV (GmDNV). Numbers represent the amino acid positions and GenBank accession numbers are provided at the end of each sequence. Identical residues in at least 60% of sequences are shown in reverse.

3.8. Electron microscopy

Electron microscopic examination of negatively stained samples from SiDNV-infected fire ants revealed numerous isometric particles with a diameter of 26.4 ± 2.7 nm as well as empty virions (Fig. 2B).

4. Discussion

Viral metagenomics is recognized as a powerful, fast, sensitive technique for identifying and discovering viruses in environmental samples (Mokili et al., 2012). Indeed, we previously employed this approach to facilitate discovery of viruses as control agents against the invasive fire ant S. invicta (Valles et al., 2008), including SINV-1, SINV-2, and SINV-3 (Valles, 2012). However, the presence of these viruses in USA populations of S. invicta limits their usefulness to augmentative releases or biopesticide development. Extensive searches (Jouvenaz, 1983; Jouvenaz et al., 1977, 1981) and intercontinental comparative ecological studies (Porter et al., 1997) have established that S. invicta escaped many of its natural enemies during the founding event(s) into the USA. The lack of natural pathogens/parasites is considered one of the primary reasons S. invicta is such a serious pest in North America (Porter et al., 1992, 1997). Classical biological control relies on identification of natural enemies in indigenous host populations (which are absent in the introduced population) followed by importation and release of the natural enemies in introduced populations. Recently, this strategy has been refined further to first identify the specific native source location of the introduced pest, which potentially increases the chance for success because the host and natural enemy are more closely matched genetically (Roderick and Navajas, 2003; Waage, 1990). The immediate source of S. invicta in the USA appears to be an area at or near Formosa, Argentina (Caldera et al., 2008). Thus, S. invicta colonies from this region of Argentina were pooled and used as source material for metagenomics/pyrosequencing aimed at identifying viruses unique to the native ants that served as the source for S. invicta in the USA. The ultimate goal of these efforts was identification of one or more viruses potentially useful as a classical biological control agent against introduced S. invicta. As a result of these efforts, SiDNV, a single stranded DNA densovirus was discovered.

Table 4 – Possible regulatory sequences identified in the SiDNV genome.

SiDNV represents the first discovery of a densovirus in an insect from the order Hymenoptera, and the first DNA virus discovery in the Formicidae. The approach we employed to acquire the SiDNV genome sequence was unique. Members of the Densovirinae typically encapsidate either the positive or negative genome strand, so a mixture of strands would be expected in any population sample of the virus. As a result, the availability of the 3’ ends of both genome strands afforded the opportunity for extension by polycytidylation and subsequent PCR with a gene specific primer and an abridged anchor primer (Invitrogen). This novel approach permitted discrimination of the virus-specific sequence from the host. The single stranded DNA genome is comprised of 5280 nucleotides, exhibits an ambisense arrangement, possesses inverted terminal repeats and hairpin structures, and encodes replicative and structural proteins in 5 ORFs with strong identities to other members of the Parvoviridae (particularly the Densovirinae). Sequence motifs for replication initiators, NTP-binding, helicase and vPLA2 were identified and shown to possess conserved residues critical to function (Fig. 3). Proteins with strong identity to densovirus capsid proteins were also present.

The SiDNV genome termini were palindromic and non-coding. A 134 nt ITR was asymmetrically positioned at each end of the genome. The NS-proximal foldback was comprised of 231 nts and formed a tight circular hairpin at nts 115–117 (Fig. 2A). The VP-proximal foldback was comprised of 155 nts and formed an inverted ‘‘J’’ or ‘‘S’’ hairpin structure in the region 5190–5216. The hairpins exhibited uniquely folded structures more consistent with a simple tight hairpin as observed for Bombyx mori densovirus (BmDNV) (Bando et al., 1990) instead of the ‘‘T’’, ‘‘J’’, or ‘‘Y’’ shapes reported in other densoviruses (Tijssen et al., 2012). Sequences consistent with certain regulatory elements were recognized in these regions (Table 4, Fig. 1B).

Fairly extensive surveys of S. invicta populations throughout northern Argentina and across the USA revealed that SiDNV was restricted to fire ants from the native source population. Thus, SiDNV is a strong candidate as a classical biological agent for introduced S. invicta. While pathology studies were not included in the present work, viruses in the Densovirinae are often quite virulent and lethal to their arthropod hosts (Kawase, 1985; van Munster et al., 2003). Ryabov et al. (2009) have shown that Dysaphis plantaginea densovirus (DplDNV) infections have a negative impact on rosy aphid reproduction, but that infection also contributes to the host’s survival by inducing wing development and promoting dispersal. Therefore, in-depth studies concerned with host specificity and host effects will be necessary before SiDNV can be considered seriously as a biological control agent of S. invicta.

Fig. 4.

Neighbor-joining tree depicting relationships of protein sequences of NS1 from members and likely members of the Densovirinae. Shaded area represents viruses with ambisense genomes. The remaining viruses possess monosense genomes. Branch supports of less than 50% are not indicated. Virus abbreviation, accession number of the sequence used are as follows: AaeDNV = Aedes aegypti densovirus NS1; YP_002854229; AalDNV = Aedes albopictus densovirus NS1; NP_694827.1; AdDNV = Acheta domestica densovirus NS1; P_227600; AgDNV = Anopheles gambiae densovirus NS1; YP_002265406; ApDNV = Acyrthosiphon pisum NS1; P_003246947; BgDNC = Blattella germanica densovirus NS1; NP_874381; BmDNV5 = Bombyx mori densovirus 5; NP_694834; CeDNV = Casphalia extranea densovirus NS1; NP_694838; CpDNV = Culex pipiens densovirus NS1; YP_002887625; CppDNV = Culex pipiens pallens densovirus NS1; ABU94969; DplDNV = Dysaphis plantaginea densovirus NS1; ACI01073; DpuDNV = Dendrolimus punctatus densovirus NS1; YP_164339; DsDNV = Diatraea saccharalis densovirus NS1; NP_046813; GmDNV = Galleria mellonella densovirus NS1; NP_899650; HaDNV = Helicoverpa armigera densovirus NS1; AFK91980; HeDNV = Haemagogus equinus densovirus NS1; AAT35223; JcDNV = Junonia coenia densovirus NS1; NP_694824; mDNVBr7 = Mosquito densovirus BR/07 NS1; YP_004222723.1; MlDNV = Mythimna loreyi densovirus NS1; NP_958099; MpDNV = Myzus persicae densovirus NS1; NP_874376; PcDNV = Planococcus citri densovirus NS1; NP_694843; PfDNV = Periplaneta fuliginosa densovirus NS1; NP_051020; PiDNV = Pseudoplusia includens densovirus NS1; YP_007003823; PmDNV = Penaeus merguiensis densovirus NS1; YP_271915; PpDNV = Papilio polyxenes densovirus NS1; YP_006589928; SfDNV = Sibine fusca densovirus NS1; YP_006576512. CPVgp1 = canine parvovirus NS1; AAV54180, served as the out group.

Phylogenetic analyses that include the SiDNV NS1 gene sequence suggest a topology similar to that of Tijssen et al. (2012). These authors place AdDNV, Blattella germanica DNV (BgDNV), and PcDNV within the genus Pefudensovirus (which includes the type species PfDNV). Inclusion of SiDNV to the phylogeny supports the independent grouping of SiDNV, PcDNV and AdDNV. However, it does not support placing these three viruses within the Pefudensovirus genus. Indeed, both phylogenies suggest the clade containing SiDNV, PcDNV, and AdDNV share a more recent common ancestor with Densoviruses rather than PfDNV. Thus, a more reasonable hypothesis is that this group represents a third independent lineage within the Densovirinae. This grouping is somewhat unexpected because of the dissimilarity between hosts; three insect orders are represented, Orthoptera (AdDNV), Homoptera, (PcDNV), and Hymenoptera (SiDNV).

The discovery of SiDNV is important because it represents the first virus potential classical biological agent that could be imported and released into the USA to provide sustainable control of the invasive pest ant, S. invicta. Indeed, densoviruses have been shown to be amenable to development as biopesticides providing a species-specific alternative to traditional insecticides (El-Far et al., 2012). Densoviruses have also been reported to exhibit potential as classical biological control agents (Bergoin and Tijssen, 1998). PfDNV was shown to cause high mortality in adult smoky-brown cockroaches, Periplaneta fuliginosa, in no-choice lab tests and large population chamber tests (Jiang et al., 2008). Mosimann et al. (2011) have recently reported that mosquito-specific densoviruses interfered with dengue viral morphogenesis, thus exhibiting potential as biological control agents against dengue virus in mosquitoes. Additional benefits of the discovery may permit use of the virus (or portions thereof) as a molecular tool. For example, a portion of the Junonia coenia DNV genome has been employed successfully as a vector to stably transfect insect cells or embryos with foreign genes (Bossin et al., 2003; Royer et al., 2001).

Acknowledgements

We thank R. Nagoshi and M.Y. Choi (USDA-ARS) for critical reviews of the manuscript. We are also grateful to Neil Sanscrainte for assistance with electron microscopy. YW is grateful to Laurent Keller for support (YW was funded by grants to Laurent Keller). Research supported in part by a grant from Infectigen. We thank the Vital-IT (https://www.vital-it.ch) Center for high-performance computing of the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics for access to the SIB BLAST Network Service. The use of trade, firm, or corporation names in this publication is for the information and convenience of the reader. Such use does not constitute an official endorsement or approval by the United States Department of Agriculture or the Agricultural Research Service of any product or service to the exclusion of others that may be suitable.

References

-

Altschul, S.F., Madden, T.L., Schaffer, A.A., Zhang, J., Zhang, Z., Miller, W., Lipman, D.J., 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 3389–3402.

-

Bando, H., Choi, H., Ito, Y., Kawase, S., 1990. Terminal structure of a densovirus implies a hairpin transfer replication which is similar to the model for AAV. Virology 179, 57–63.

-

Bergoin, M., Tijssen, P., 1998. Biological and molecular properties of densoviruses and their use in protein expression and biological control. In: Miller, L.K., Ball, A. (Eds.), The Insect Viruses. Plenum Publishing Corporation, New York, pp. 141–169.

-

Bergoin, M., Tijssen, P., 2000. Molecular biology of Densovirinae. Contrib. Microbiol. 4, 12–32.

-

Berns, K.I., 1990. Parvovirus replication. Microbiol. Rev. 54, 316–329.

-

Bossin, H., Fournier, P., Royer, C., Barry, P., Cerutti, P., Gimenez, S., Couble, P., Bergoin, M., 2003. Junonia coenia densovirus-based vectors for stable transgene expression in Sf9 cells: influence of the densovirus sequences on genomic integration. J. Virol. 77, 11060–11071.

-

Caldera, E.J., Ross, K.G., DeHeer, C.J., Shoemaker, D., 2008. Putative native source of the invasive fire ant Solenopsis invicta in the USA. Biol. Invas. 10, 1457–1479.

-

Callcott, A.M., Collins, H.L., 1996. Invasion and range expansion of imported fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in North America from 1918–1995. Fla. Entomol. 79, 240–251.

-

El-Far, M., Szelei, J., Yu, Q., Fediere, G., Bergoin, M., Tijssen, P., 2012. Organization of the ambisense genome of the Helicoverpa armigera densovirus. J. Virol. 86, 7024.

-

Fédière, G., Li, Y., Zadori, Z., Szelei, J., Tijssen, P., 2002. Genome organization of Casphalia extranea densovirus, a new iteravirus. Virology 292, 299–308.

-

Ghosh, R.C., Ball, B.V., Willcocks, M.M., Carter, M.J., 1999. The nucleotide sequence of sacbrood virus of the honey bee: an insect picorna-like virus. J. Gen. Virol. 80 (Pt 6), 1541–1549.

-

Jiang, H., Zhou, L., Zhang, J.M., Dong, H.F., Hu, Y.Y., Jiang, M.S., 2008. Potential of Periplaneta fuliginosa densovirus as a biocontrol agent for smoky-brown cockroach, P. fuliginosa. Biol. Control 46, 94–100.

-

Jouvenaz, D.P., 1983. Natural enemies of fire ants. Fla. Entomol. 66, 111–121.

-

Jouvenaz, D.P., Kimbrough, J.W., 1991. Myrmecomyces annellisae gen. nov., sp. nov. (Deuteromycotina: Hypomycetes), an endoparasitic fungus of fire ants, Solenopsis spp. (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Mycol. Res. 95, 1395–1401.

-

Jouvenaz, D.P., Allen, G.E., Banks, W.A., Wojcik, D.P., 1977. A survey for pathogens of fire ants, Solenopsis spp. in the southeastern United States. Fla. Entomol. 60, 275–279.

-

Jouvenaz, D.P., Lofgren, C.S., Banks, W.A., 1981. Biological control of imported fire ants; a review of current knowledge. Bull. Entomol. Soc. Am. 27, 203–208.

-

Kathirithamby, J., Johnston, J.S., 2001. Stylopization of Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) by Caenocholax fenyesi (Strepsiptera: Myrmecolacidae) in Texas. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 85, 293–297.

-

Kawase, M., 1985. Pathology associated with densovirus. In: Maramosh, K., Sherman, E. (Eds.), Viral Insecticides for Biological Control. Academic Press, New York, pp. 197–231.

-

Knell, J.D., Allen, G.E., 1977. Light and electron microscope study of Thelohania solenopsae n. sp. (Microsporida: Protozoa) in the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. J. Invert. Pathol. 29, 192–200.

-

Koonin, E.V., 1993. A common set of conserved motifs in a vast variety of putative nucleic acid-dependent ATPases including MCM proteins involved in the initiation of eukaryotic DNA replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 2541–2547.

-

Lacey, L.A., Frutos, R., Kaya, H.K., Vail, P., 2001. Insect pathogens as biological control agents: do they have a future? Biol. Control 21, 230–248.

-

Loh, E.Y., Elliott, J.F., Cwirla, S., Lanier, L.L., Davis, M.M., 1989. Polymerase chain reaction with single-sided specificity: analysis of T cell receptor delta chain. Science 243, 217–220.

-

Mokili, J.L., Rohwer, F., Dutilh, B.E., 2012. Metagenomics and future perspectives in virus discovery. Curr. Opin. Virol. 2, 63–77.

-

Mosimann, A.L.P., Bordignon, J., Mazzarotto, G.C.A., Motta, M.C.M., Hoffmann, F., Santos, C.N.D., 2011. Genetic and biological characterization of a densovirus isolate that affects dengue virus infection. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 106, 285–292.

-

Nuesch, J.P.F., Cotmore, S.F., Tattersall, P., 1995. Sequence motifs in the replicator protein of parvovirus MVM essential for nicking and covalent attachment to the viral origin: identification of the linking tyrosine. Virology 209, 122–135.

-

Pereira, R.M., 2004. Occurrence of Myrmicinosporidium durum in red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, and other new host ants in eastern United States. J. Invert. Pathol. 86, 38–44.

-

Pereira, R.M., Williams, D.F., Becnel, J.J., Oi, D.H., 2002. Yellow-head disease caused by a newly discovered Mattesia sp. in populations of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. J. Invert. Pathol. 81, 45–48.

-

Porter, S.D., 1998. Biology and behavior of Pseudacteon decapitating flies (Diptera: Phoridae) that parasitize Solenopsis fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Fla. Entomol. 81, 292–309.

-

Porter, S.D., Fowler, H.G., Mackay, W.P., 1992. Fire ant mound densities in the United States and Brazil (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 85, 1154–1161.

-

Porter, S.D., Williams, D.F., Patterson, R.S., Fowler, H.G., 1997. Intercontinental differences in the abundance of Solenopsis fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): escape from natural enemies? Environ. Entomol. 26, 373–384.

-

Roderick, G.K., Navajas, M., 2003. Genes in new environments: genetics and evolution in biological control. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4, 889–899.

-

Royer, C., Bossin, H., Romane, C., Bergoin, M., Couble, P., 2001. High amplification of a densovirus-derived vector in larval and adult tissues of Drosophila. Insect Mol. Biol. 10, 275–280.

-

Ryabov, E.V., Keane, G., Naish, N., Evered, C., Winstanley, D., 2009. Densovirus induces winged morphs in asexual clones of the rosy apple aphid, Dysaphis plantaginea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8465–8470.

-

Schmid-Hempel, P., 1998. Parasites in Social Insects. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

-

Tamura, K., Peterson, D., Peterson, N., Stecher, G., Nei, M., Kumar, S., 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739.

-

Thompson, J.D., Higgins, D.G., Gibson, T.J., 1994. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680.

-

Tijssen, P., Agbandje-McKenna, M., Almendral, J.M., Bergoin, M., Flegel, T.W., Hedman, K., Kleinschmidt, J., Li, Y., Pintel, D.J., Tattersall, P., 2012. Family Parvoviridae. In: King, A.M. et al. (Eds.), Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, Amsterdam, pp. 405–425.

-

Trager, J.C., 1991. A revision of the fire ants, Solenopsis geminata group (Hymenoptera, Formicidae, Myrmicinae). J.N.Y. Entomol. Soc. 99, 141–198.

-

Tschinkel, W.R., 2006. The Fire Ants. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

-

Valles, S.M., 2012. Positive-strand RNA viruses infecting the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Psyche 2012, 1–14.

-

Valles, S.M., Hashimoto, Y., 2009. Isolation and characterization of Solenopsis invicta virus 3, a new postive-strand RNA virus infecting the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Virology 388, 354–361.

-

Valles, S.M., Strong, C.A., Dang, P.M., Hunter, W.B., Pereira, R.M., Oi, D.H., Shapiro, A.M., Williams, D.F., 2004. A picorna-like virus from the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta: initial discovery, genome sequence, and characterization. Virology 328, 151–157.

-

Valles, S.M., Strong, C.A., Hashimoto, Y., 2007. A new positive-strand RNA virus with unique genome characteristics from the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Virology 365, 457–463.

-

Valles, S.M., Strong, C.A., Hunter, W.B., Dang, P.M., Pereira, R.M., Oi, D.H., Williams, D.F., 2008. Expressed sequence tags from the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta: annotation and utilization for discovery of viruses. J. Invert. Pathol. 99, 74–81.

-

Valles, S.M., Porter, S.D., Choi, M.Y., Oi, D.H., 2013. Successful transmission of Solenopsis invicta virus 3 to Solenopsis invicta fire ant colonies in oil, sugar, and cricket bait formulations. J. Invert. Pathol. 113, 198–204.

-

van Munster, M., Dullemans, A.M., Verbeek, M., van den Heuvel, J.F., Reinbold, C., Brault, V., Clerivet, A., van der Wilk, F., 2003. Characterization of a new densovirus infecting the green peach aphid Myzus persicae. J. Invert. Pathol. 84, 6–14.

-

Waage, J.K., 1990. Ecological theory and the selection of biological control agents. In: Mackauer, M., Ehler, L.E. (Eds.), Critical Issues in Biological Control. Intercept, Andover, pp. 135–157.

-

Wang, J., Zhang, J., Jiang, H., Liu, C., Yi, F., Hu, Y., 2005. Nucleotide sequence and genomic organization of a newly isolated densovirus infecting Dendrolimus punctatus. J. Gen. Virol. 86, 2169–2173.

-

Williams, D.F., Knue, G.J., Becnel, J.J., 1998. Discovery of Thelohania solenopsae from the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, in the United States. J. Invert. Pathol. 71, 175–176.

-

Williams, D.F., Oi, D.H., Porter, S.D., Pereira, R.M., Briano, J.A., 2003. Biological control of imported fire ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Am. Entomol. 49, 150–163.

-

Zádori, Z., Szelei, J., Lacoste, M.-C., Li, Y., Gariepy, S., Raymond, P., Allaire, M., Nabi, I.R., Tijssen, P., 2001. A viral phospholipase A2 is required for parvovirus infectivity. Dev. Cell 1, 291–302.

-

Zuker, M., 2003. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3406–3415.