Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 23 February 2010

Changes in reproductive roles are associated with changes in gene expression in fire ant queens

Y. Wurm, J. Wang, L. Keller

Molecular Ecology, 2010, 19:1200-11

Abstract

In species with social hierarchies, the death of dominant individuals typically upheaves the social hierarchy and provides an opportunity for subordinate individuals to become reproductives. Such a phenomenon occurs in the monogyne form of the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, where colonies typically contain a single wingless reproductive queen, thousands of workers and hundreds of winged nonreproductive virgin queens. Upon the death of the mother queen, many virgin queens shed their wings and initiate reproductive development instead of departing on a mating flight. Workers progressively execute almost all of them over the following weeks. To identify the molecular changes that occur in virgin queens as they perceive the loss of their mother queen and begin to compete for reproductive dominance, we collected virgin queens before the loss of their mother queen, 6 h after orphaning and 24 h after orphaning. Their RNA was extracted and hybridized against microarrays to examine the expression levels of approximately 10000 genes. We identified 297 genes that were consistently differentially expressed after orphaning. These include genes that are putatively involved in the signalling and onset of reproductive development, as well as genes underlying major physiological changes in the young queens.

Introduction

Reproduction is monopolized by only a small number of individuals in many group-living animals. Which individuals reproduce can be determined by fights for dominance or territory, by seniority within the group, by genotype and by other factors (Keller 1993; Keller & Reeve 1994; Solomon & French 1997; Keller & Ross 1998). The social stimuli responsible for changes in reproductive hierarchies are well documented in many animals (Solomon & French 1997) and several studies focused on identifying molecular differences between established dominants and subordinates (Renn et al. 2004; Grozinger et al. 2007; Roberge et al. 2008). However, only a few studies examined the molecular and physiological mechanisms linking social stimuli to changes in reproductive status. In the cichlid fish Astatotilapia burtoni, disappearance of the dominant male leads to rapid reactions in subordinate males, including dramatic changes in body coloration and behaviour, growth of certain brain regions and increases in brain levels of gonadotropin releasing hormone 1 and early growth response factor 1 (White et al. 2002; Burmeister et al. 2005). Similarly, the transition from subordinate to breeder status in white-browed sparrow weavers is accompanied by changes in type of song, morphology of song-related brain areas and an increase in levels of two hormone receptors and two synaptic proteins in a song-related brain area (Voigt et al. 2007). Changes in brain morphology also accompany the transition from subordinate to breeder status in naked mole rats (Holmes et al. 2007). While the previous studies provide valuable insights into the mechanisms involved in social status differences, they either focused on brain morphology, a few candidate genes during the transition from subordinate to breeder or fixed gene expression differences in established dominance hierarchies.

Social insects provide excellent models for studying the mechanisms involved in reproductive competition (Roseler et al. 1984; Roseler 1991; Keller 1993; Neumann et al. 2000; Dietemann et al. 2006). In eusocial bees, wasps and ants there is a clear division of labour with one or a few individuals monopolizing reproduction. Differences in reproductive roles are generally associated with tremendous physiological and behavioural modifications (Wilson 1971; Bourke & Franks 1995). This has led to many behavioural and hormone-based experiments including some in fire ants that have even succeeded in isolating glands and compounds involved in maintaining social dominance hierarchies (Vander Meer et al. 1980; Vargo & Laurel 1994; Vargo 1999; Vargo & Hulsey 2000; Brent & Vargo 2003). Investigating social life at a broad molecular scale has only recently become possible with the development of genomic tools for social insects (The Honey Bee Genome Sequencing Consortium 2006; Wang et al. 2007; Wurm et al. 2009). Some of the first studies focused on identifying gene expression differences between reproductive and nonreproductive castes (Pereboom et al. 2005; Grozinger et al. 2007; Gräff et al. 2007; Weil et al. 2009), and others have investigated the link between social context and gene activity (Toth et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2008; Grozinger et al. 2003). However, very little still is known about the changes in gene expression associated with changes in reproductive roles.

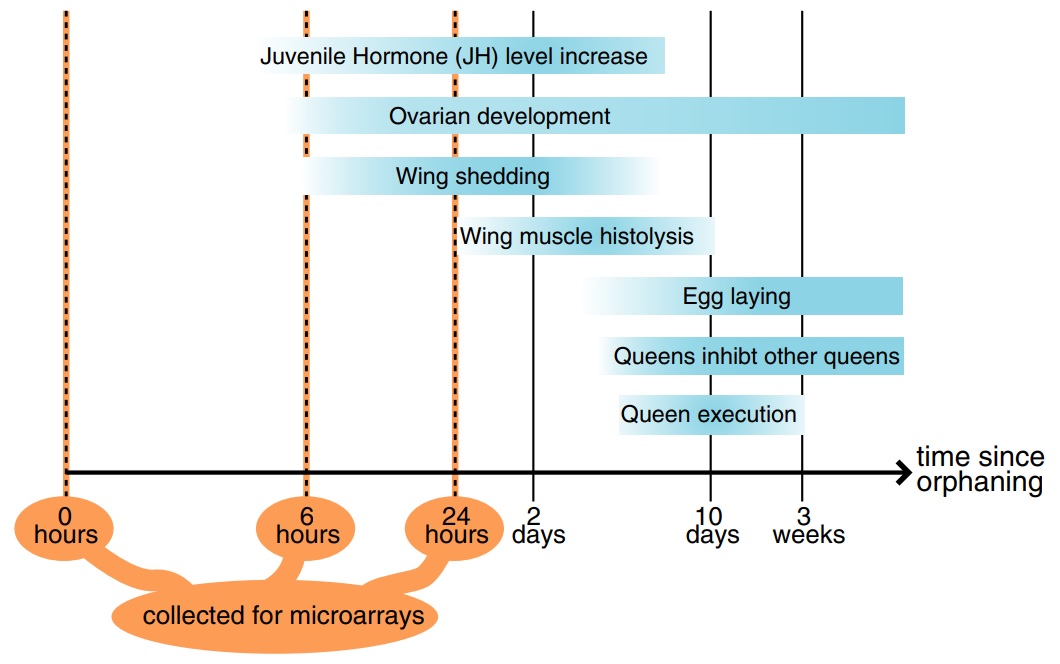

The red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta, represents a particularly attractive model for studying the onset of competition between subordinate individuals. During the reproductive season, colonies of the monogyne form (single queen per colony) can produce hundreds or even thousands of young virgin daughter queens. These virgin queens spend the next few weeks building up fat reserves within the colony. Once they reach sexual maturity, they do not immediately become reproductive because supernumerary reproductive queens are executed by the workers (Vargo & Porter 1993; Vargo & Laurel 1994). Thus, virgin queens remain in the parental nest without reproducing until they participate in a mating flight and attempt to found their own colony. However, a remarkable alternative exists in S. invicta when the mother queen dies. During the days following orphaning, many young queens shed their wings and initiate reproductive development. Additionally, these young queens begin emitting pheromonal signals to which nestmate queens and workers react. When virgin nestmate queens perceive such signals, they refrain from shedding their own wings and initiating reproductive development (Fletcher et al. 1983; Vargo 1999). When orphaned workers perceive pheromonal signals emitted by queens initiating reproductive development, they begin to tend to these queens (Fletcher & Blum 1981). However, if several queens produce signals associated with initiation of reproductive development, the workers will progressively execute almost all of them over the next few weeks (Fletcher & Blum 1983; timeline of events summarized in Fig. 1). The surviving virgin queen or queens are thus ‘elected’ by workers to replace the mother queen. These queens are unmated and thus unable to replenish the colony’s worker force. However, until the colony’s workers have died out, the queens can lay thousands of haploid eggs that develop into haploid reproductive males (Tschinkel 2006). Contrary to many other ant species, S. invicta workers lack functional ovaries and are completely sterile (Tschinkel 2006).

Fig. 1

Timeline of postorphaning events in the fire ant (based on the following studies: Barker 1979; Fletcher & Blum 1981, 1983; Vargo & Laurel 1994; Vargo 1999; Burns et al. 2007).

The aim of this study was to identify the molecular changes that occur in virgin queens as they perceive the loss of their mother queen and begin to compete for reproductive dominance. For this, we conducted orphaning simulations and examined gene expression using a microarray representing some 10 000 genes. We identified several categories of genes that are consistently upregulated after orphaning, some of which are also upregulated at the onset of reproductive development in other insects.

Materials and methods

Ant collection and rearing

Monogyne S. invicta fire ant colonies, each containing at least 50 winged virgin queens were collected from a single population in Athens and Lexington, GA, USA, in June 2006. The genetic variability between colonies is moderate in the USA because only few queens were introduced to the USA from South America in the 1930s (Ross et al. 1993; Ross & Shoemaker 2008). All colonies were returned to the laboratory and reared for 1 month under standard conditions (Jouvenaz et al. 1977). We selected eight colonies that were healthy and of similar size (between 5000 and 10 000 workers) and determined that they were of the monogyne social form using several lines of evidence. Nest shape, nest density and worker size distribution were used to make initial identifications of social form in the field (Shoemaker et al. 2006). Subsequently, monogyny was confirmed for each colony by the presence of a single, highly physogastric, wingless queen. Finally, the social form was further verified by electrophoretically detecting only the B but not the b allele of Gp-9 in pooled samples of 20 workers from each colony (lack of the b allele is diagnostic for monogyny in S. invicta in the USA; Ross 1997; Keller & Ross 1998; Krieger & Ross 2002; Shoemaker et al. 2006). In each of these colonies we weekly removed all queenand male-destined brood (identified by their large size) during 4 weeks to ensure that all the winged queens were field reared and sexually mature.

Orphaning simulation, RNA isolation and microarray hybridization

To examine the onset of the molecular reaction to orphaning we collected virgin (winged) queens just before orphaning as well as 6 and 24 h after orphaning (subsequently referred to as time points t0h, t6h and t24h). For t0h, we haphazardly collected five virgin queens from the foraging area of each source colony and individually flash froze them with liquid nitrogen in tubes containing 1 g of 1.4-mm Zirconium Silicate beads (QuackenBush). As virgin queens emit pheromonal signals after orphaning that are similar to those of a functional queen (Fletcher et al. 1983; Vargo 1999), we split each of the eight colonies into 10 fragments each containing one virgin queen as well as 2 g of workers and brood. The density of workers and brood in these small colonies was comparable with that found in the source colonies and the stress imposed by the splitting was probably minimal as S. invicta is an opportunistic species that changes nests often in its native habitat. When no reproductive queen is present, virgin queens usually shed their wings and initiate reproductive development (Fletcher & Blum 1981; Tschinkel 2006; Burns et al. 2007). We harvested half of the 80 virgin queens after 6 h (t6h) and the remaining queens after 24 h (t24h). All collected queens were individually flash frozen immediately after collection as described for t0h. Samples were then stabilized until RNA isolation by the addition of 900 lL of cold Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) followed by homogenization with a FastPrep instrument (MP Biomedicals) and storage at )80 °C. In summary, we thus collected five queens at t0h, five queens at t6h and five queens at t24h from each of eight source colonies, constituting eight biological replicates for our experiment (see also Fig. S1). We chose to examine whole bodies because multiple body parts are involved in the physiological processes occurring postorphaning. These include for example the antennae perceiving the mother queen (Vargo & Laurel 1994), the corpora allata for producing juvenile hormone (JH) (Brent & Vargo 2003), thoracic wing muscles that are histolysed and development of ovaries in the abdomen (Tschinkel 2006). We pooled five individuals from each replicate to reduce the impact of between-individual differences (Kendziorski et al. 2005) and conducted eight replicates to obtain sufficient statistical power with a feasible workload. In comparison, other studies that examined the effects of social context or mating on gene expression used four replicates from a single Drosophila strain (McGraw et al. 2004), six replicates using different bees from a single colony (Kocher et al. 2008), six replicated sets of fish (Renn et al. 2008; Roberge et al. 2008) and pools of individuals from 16 independent pairs of ant colonies (Wang et al. 2008).

Total RNA was isolated from all individuals using the Trizol protocol. RNA was pooled from five individuals per source colony for each time point and treated with DNA free (Ambion). Subsequently, impurities were filtered away with MicroCon-30 spin columns (Millipore) and RNA quality was assessed on a 1% agarose gel prior to amplification using the MessageAmp II kit (Ambion). Amplified mRNA samples from the eight colonies at three timepoints (t0h, t6h and t24h) were labelled, hybridized to microarrays according to a dyebalanced loop design (Fig. S1) and scanned as previously described (Wang et al. 2008). For all procedures, precautions including randomization of sample order were taken to avoid introducing unwanted biases. Microarray construction has been previously described (Wang et al. 2007). In brief, a normalized cDNA library was constructed from pooled RNA isolated from all fire ant castes and developmental and adult stages. More than 22 000 randomly selected cDNA clones were then amplified by PCR. Each PCR-amplified cDNA clone was used for 5’-sequencing (approximately 600 bp obtained from each clone) as well as printing onto aldehydesilane-coated slides (Nexterion Slide AL) using a GeneMachines OmniGrid 300 spotting robot.

Microarray analysis

We followed a standard microarray analysis procedure, guided by the documentation of the Bioconductor limma package (Gentleman et al. 2004; Smyth 2004; Smyth et al. 2005). In brief, median signal and background levels for each probe were extracted from scanned microarray images using Axon Genepix software. The limma 2.16 package (Smyth 2004) in R 2.8.1 (The R Development Core Team 2007) was used for Normexp background correction, Print-tip Loess normalization within arrays, and Aquantile normalization between arrays (Smyth & Speed 2003). The arrayQualityMetrics package (Kauffmann et al. 2009) and custom R scripts were used for quality control. The 18 444 S. invicta cDNA spots yielding a single PCR band (Wang et al. 2007) and passing visual and automated inspection were used for analysis. We constructed a design matrix incorporating effects for sampling times (t0h, t6h and t24h), biological replicate (eight colonies) and the two dyes. The model that is fit to each gene may thus be represented as ‘expression = timepoint + replicate + dye’. The limma package was used for Bayesian fitting of the model. Differential expression was determined for the contrasts ‘t24h vs. t0h’, ‘t24h vs. t6h’ and ‘t6h vs. t0h’ according to the nested F method in limma. Briefly, a moderated Ftest determined that 521 microarray clones were differentially expressed for at least one of the contrasts with a 10% false discovery rate (FDR) (Benjamini & Hochberg 1995). Subsequently, significance of differential expression was assigned to one or several contrasts. In comparison, the effects of mating on honey bees queens were determined with 5% FDR (Kocher et al. 2008), a comparison between fire ant workers from different social structures used 10% FDR (Wang et al. 2008) and the effect of the presence of brood on honey bee workers was determined with 30% FDR (Alaux et al. 2009).

Sequence data, annotation and gene category analysis

The published sequences of all microarray clones (Wang et al. 2007) were assembled along with data from two runs of 454 sequencing of independently constructed cDNA libraries (Y. Wurm, D. Hahn and DD. Shoemaker; DH and DDS are at USDA-ARS, Gainesville, private communication). High-quality sequence information was obtained for 16 227 of the 18 444 S. invicta cDNA clones used for gene expression analysis. This was also the case for 475 of the 521 significantly differentially expressed clones.

Annotation was obtained via several methods. First, we ran NCBI BLASTX 2.2.16 to compare assembled fire ant sequences with the nonredundant protein database (EMBL release 99). We retained informative gene descriptions of hits with E-value <10-5. Second, gene ontology (GO) (Ashburner et al. 2000) annotations were inferred using BLASTX as previously described (Wurm et al. 2009). Finally, each fire ant sequence was manually assigned a single descriptive category. The manually assigned gene category putatively encapsulates the general function of each sequence and is derived subjectively by examining the SwissProt or Ensembl database entries of the five best BLASTX hits (E-values <10-5 ), with an emphasis on GO, Interpro and PANTHER annotations. The manual annotation comprises a total of 34 general gene categories (J. Wang, M. Nicolas and L. Ometto, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, private communication). Overrepresentation of manually assigned gene categories and GO categories was determined, respectively, using exact one-sided Fisher tests in R and the Elim test from the topGO Bioconductor package (Alexa et al. 2006) limited to categories containing at least 10 fire ant genes. These included 514 Biological Processes, 131 Cellular Components and 171 Molecular Functions.

Comparison with data from other species

We wanted to determine the extent to which gene expression differences linked to changes in social context and reproductive status in this study are likely to play similar roles in other insects. To do this, we downloaded lists of significantly over- and under-expressed genes from studies that examined the transition to reproduction in flies, bees and mosquitoes (Lawniczak & Begun 2004; McGraw et al. 2004; Kocher et al. 2008; Rogers et al. 2008) as well as the fixed differences in reproductive status between honey bee queens and workers (Grozinger et al. 2007). Mapping between microarray probes and coding sequences was either provided by the study’s authors (for Grozinger et al. 2007), obtained by BLASTN of probe sequences to coding sequences (for Kocher et al. 2008) or downloaded (for Lawniczak & Begun 2004; McGraw et al. 2004; Rogers et al. 2008) from BioMart (Haider et al. 2009). Orthology information was required to compare lists of significant genes between ants and the other species; however, such information is practically nonexistent. This is in part because and only partial transcriptome and no proteome or genomic sequence data are published for ants. To obtain orthology information, we modified the Inparanoid orthologue identification pipeline (Remm et al. 2001) as follows: BLASTX was replaced with TBLASTX and stringency was reduced so that match areas must span at least 25% of the longer sequence with actual matching segments aligning with at least 10% of the longer sequence. We independently ran this modified Inparanoid pipeline on the assembled fire ant sequences and the complete set of coding sequences of each of the following species: Drosophila melanogaster (Flybase release 5.9), Apis mellifera (Honey Bee Official Gene Set pre-release 2) and Anopheles gambiae (AgamP3.4).

To determine the extent of overlap between two lists of significant genes, we constructed a two-by-two contingency table containing: the number of orthologous genes in both lists, the number of genes examined in the relevant studies but not part of the significant lists and the numbers of genes that were examined in both studies but present in only one of the two lists of significant genes. Subsequently, we conducted an exact one-sided Fisher test to determine whether the number of genes in both lists was higher than would be expected by chance. Only significant results (P < 0.05) are reported.

We determined the extents of overlap between two lists of significant genes from our study (the 146 genes upregulated at one point after orphaning and the 152 genes downregulated at one point after orphaning) and the lists of genes from each of the other studies. This was possible for a reduced set of genes that are both putatively orthologous between fire ants and the species from the other study and present on both the ant microarray and the microarray used in the other study. For the Grozinger et al. (2007) study, we report significant overlap comparing the list of genes upregulated at one point after orphaning in our study with the list of 549 bee genes in the Honey Bee Official Gene Set that were more highly expressed in honey bee queens than in reproductive workers as well as the list of 619 bee genes that were more highly expressed in honey bee queens than in sterile workers. For the Kocher et al. (2008) study, we report significant overlap comparing the list of genes upregulated at one point after orphaning in our study with the list of 441 bee genes that were more highly expressed in mated than virgin honey bee queens, as well as with the list of 356 genes that were more highly expressed in honey bee queens that were mated but not yet laying eggs than in queens that were mated and egg-laying. For all remaining comparisons of pairs of lists of significant ant and honey bee genes, the overlaps were either nonsignificant, or were not examined because they concerned five genes or less.

For the Rogers et al. (2008) study, we obtained results comparing our two fire ant gene lists with a combined list of 1663 Anopheles genes that were either more highly expressed in females 2, 6 and 24 h after mating than in virgins or more highly expressed 6 h than 2 or 24 h than 6 h after mating, as well as with the complementary list of 1586 genes that were less highly expressed in virgins than in mated female Anopheles. For the McGraw et al. (2004) and Lawniczak & Begun (2004) studies, we compared our results with all individual lists of Drosophila genes that were differentially expressed in response to different aspects of mating, as well as with a combined list of all mating-response genes they had identified.

Results

Differential gene expression after orphaning

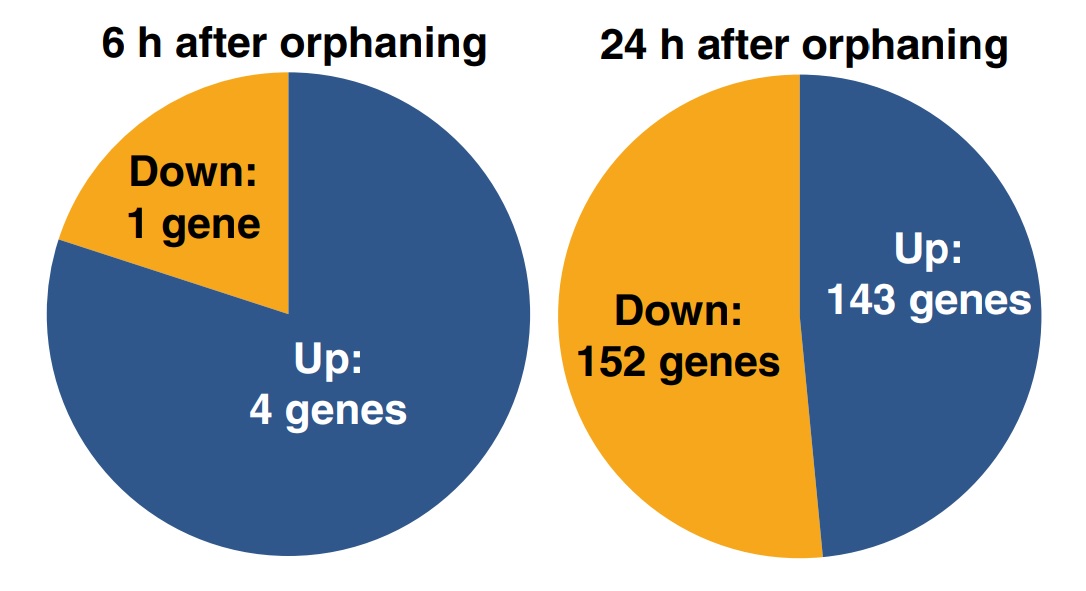

Four hundred and seventy-five of the 16 227 sequenced cDNA clones, putatively representing 297 genes, were significantly differentially expressed between the samples of virgin queens collected 0, 6 and 24 h after orphaning (respectively, t0h, t6h and t24h). The remaining genes were either expressed similarly before and after orphaning, were highly variable between biological replicates or yielded signals too weak for reliable assessment of differential expression. Among the 297 significantly differentially expressed genes, four were upregulated within 6 h of orphaning, while one was downregulated. One hundred and forty-four genes were more highly expressed 24 h after orphaning than at t0h or at t6h including one of the four genes that was already upregulated after 6 h, while a total of 152 genes were significantly downregulated after 24 h (Fig. 2). One of the genes significantly upregulated after 6 h was significantly downregulated between 6 and 24 h. The significant genes are listed in Tables S1 and S2. These gene expression changes precede or are independent of wing shedding since none of 40 virgin queens collected 6 h after orphaning and only three of 40 virgin queens collected 24 h after orphaning had shed their wings.

Fig. 2

Numbers of genes significantly differentially expressed in young fire ant queens within 6 (left) and 24 h of orphaning (right).

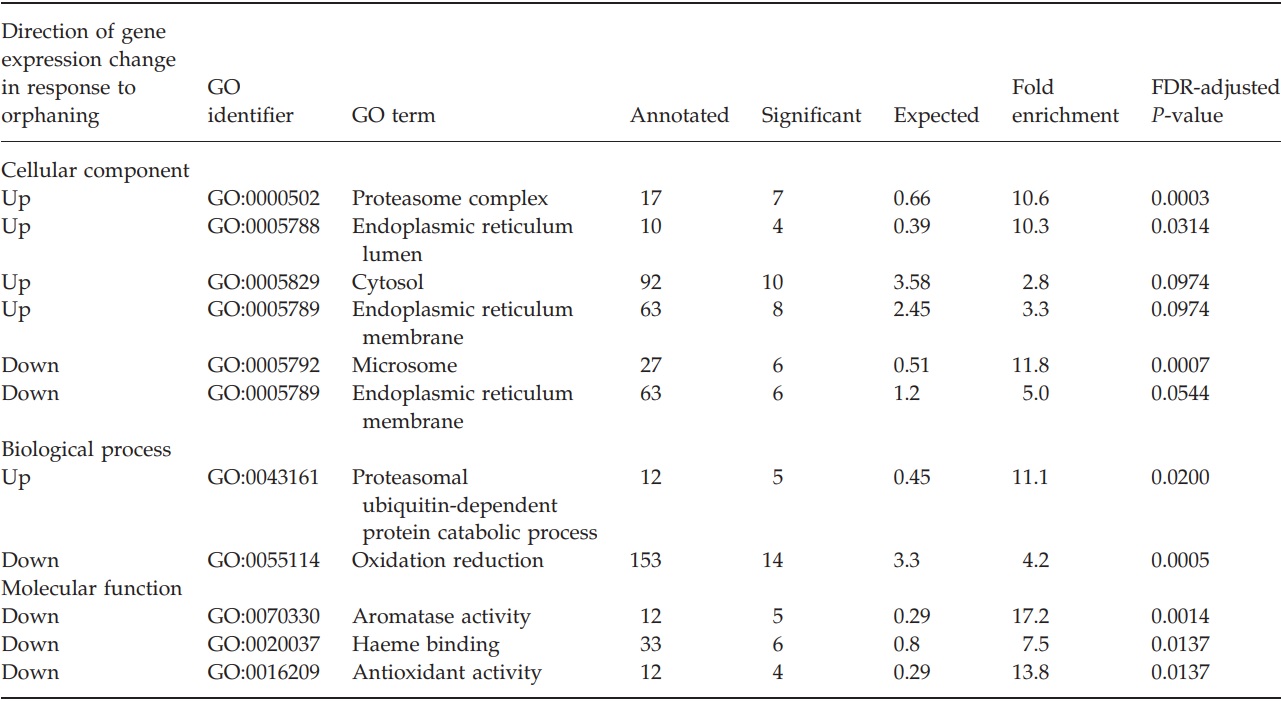

Gene set enrichment analysis

We bioinformatically annotated the genes that were significantly upregulated or downregulated after orphaning and compared their annotations with the annotations of all genes examined on the microarray by using two different annotation methods. From our manually assigned annotation categories, two gene categories were overrepresented among upregulated genes. These were proteasome (11 observed, 1.2 expected, exact one-sided Fisher test P = 1 × 10-7) and protein transport (10 observed, 1.5 expected, exact one-sided Fisher test P = 4 × 10-6). No other manually assigned annotation categories were overrepresented among up or downregulated genes. From the BLAST-inferred GO categories, several categories were overrepresented among up- and downregulated genes (complete list in Table 1). In particular, genes putatively part of the proteasomal complex were overrepresented among the upregulated genes (7 observed, 0.7 expected, P = 0.0003, topGO Elim test, adjusted for 10% FDR). Among downregulated genes, those putatively located in microsomes and involved in oxidation reduction were overrepresented (respectively, 6 observed, 0.5 expected, FDR-adjusted topGO Elim test P = 0.0007, and 14 observed, 3.3 expected, FDR adjusted topGO Elim test P = 0.0005). Additionally, genes that putatively have aromatase activity were overrepresented among the significantly downregulated genes (5 observed, 0.3 expected, FDR-adjusted topGO Elim test P = 0.0014). In fact, all five of these genes are putative Cytochrome P450s.

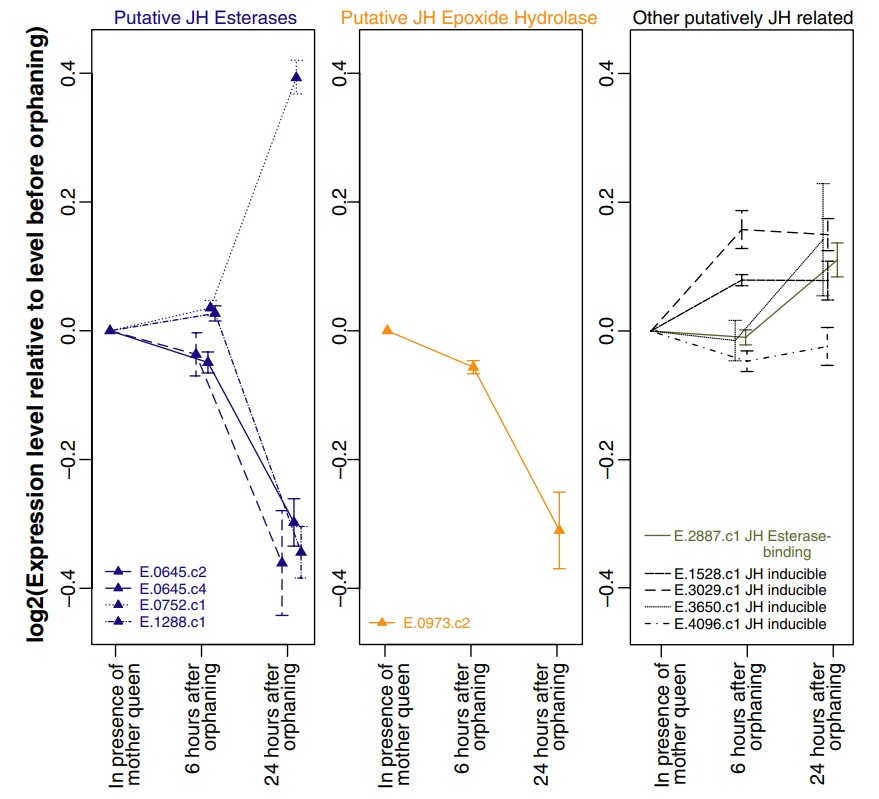

Genes related to juvenile hormone metabolism

Among the 297 genes significantly differentially expressed in orphaned compared with nonorphaned queens, five have sequence similarity to genes from other species that are involved in JH metabolism or response. In particular, three putative JH esterases were significantly downregulated after orphaning, while one was significantly upregulated. Additionally, a putative JH epoxide hydrolase was significantly downregulated after orphaning. Several putative JH inducible genes as well as a putative JH esterase-binding gene showed nonsignificant increases in expression level after orphaning (Fig. 3).

Comparison of fire ant results with data from honey bees

To determine whether the differentially expressed genes identified in our study are also differently expressed between reproductive and nonreproductive individuals in honey bees, we compared our results with the studies of Grozinger et al. (2007) and Kocher et al. (2008).

Table 1 – Gene ontology annotations that are significantly enriched among genes that are significantly upregulated or downregulated after orphaning.

Fig. 3

Expression levels of genes related to Juvenile Hormone (JH) metabolism and response in virgin fire ant queens that are either still in presence of their mother queen or have been orphaned for 6 or 24 h. Only genes with multiple clones on the microarray are shown. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean expression levels as obtained by independent clones. Genes for which at least one representative clone is significantly differentially expressed after orphaning are indicated by triangles.

The first of the two studies identified genes differentially expressed between brains of honey bee queens and workers. We identified a subset of 902 ant-bee orthologues examined in both that study and ours. Genes upregulated in orphaned fire ant queens were enriched for genes upregulated in brains of queen bees relative to brains of reproductive workers (12 observed, 7.5 expected, exact one-sided Fisher test P = 0.005). There was no significant overlap between other pairs of lists of genes from the two studies. Among the twelve genes that overlap between the groups of significantly upregulated ant and bee genes (Table S3), four are part of the manually assigned gene category proteasome (0.2 expected, exact one-sided Fisher test P = 1 × 10-4).

The other study identified genes differentially expressed between virgin and mated honey bee queens (Kocher et al. 2008). Among 2286 ant-bee orthologues examined in our study as well as the bee study, 13 genes were more highly expressed in response to orphaning in fire ants and in response to mating in honey bee queens (7.7 expected, exact one-sided Fisher test P = 0.038, genes listed in Table S4). Among the 13 genes that overlap between the two gene lists, four are part of the manually assigned gene category proteasome (0.2 expected, exact one-sided Fisher test P = 1 × 10-4). There was no significant overlap between other pairs of lists of genes from the two studies.

Comparison of fire ant results with data from dipterans

To determine whether the differentially expressed genes identified in our study are also involved in the transition towards reproduction in other insects, we compared our results with those from studies conducted in Anopheles and Drosophila. The comparison of our results with those of a study on the effects of mating in female A. gambiae mosquitoes for 1682 orthologues ant-Anopheles orthologues (Rogers et al. 2008) revealed that genes whose level of expression increased after orphaning in S. invicta queens are enriched for genes that are upregulated after mating in Anopheles (36 observed, 20.6 expected, exact one-sided Fisher test P = 8 × 10-5, genes listed in Table S5). There was no significant overlap between other pairs of lists of genes from the two studies. Six of the 36 genes identified in both studies are part of the manually assigned gene category proteasome (0.5 expected, exact one-sided Fisher test P = 3 × 10-5). Similar gene expression studies were also performed in the fruit fly D. melanogaster. We found no significant overlap between expression changes due to orphaning in fire ant queens and changes due to mating in female Drosophila (Lawniczak & Begun 2004; McGraw et al. 2004) nor between orphaned fire ant queens and specific aspects of Drosophila mating: the mating process itself (without receiving sperm), receiving sperm or receiving particular accessory proteins normally part of sperm (McGraw et al. 2004).

Discussion

We used microarrays to conduct a genome-wide survey of gene expression in virgin S. invicta fire ant queens over the 24 h that follow orphaning from their mother queen. We identified five genes that are consistently differentially expressed within 6 h of orphaning. These early response genes may be responsible for some of the additional 292 gene expression changes that take place within 24 h of orphaning. The annotations of the differentially expressed genes indicate that they potentially are involved in many different functions, including signalling reproductive status, reproductive development, proteasomal activity, protein transport and regulation of chromatin structure and transcription. We discuss each in turn.

Genes potentially involved in signalling of reproductive status

The pheromones that the mother queen uses to signal her presence and fertility are currently unknown. Our study revealed that Glutathione S-transferase (GST) is the only gene downregulated in virgin queens 6 h after orphaning. Furthermore, an additional GST as well as five Cytochrome P450s are significantly downregulated in virgin queens within 24 h of orphaning. Both GSTs and Cytochrome P450s are known to be involved in degrading foreign and endogenous compounds (Feyereisen 1999; Maibeche-Coisne et al. 2004; de Montellano 2005). We speculate that the virgin queens may use these genes to degrade fertility signals produced by the mother queen. This could be important if maternal fertility signals also triggered reproductive development in the virgins. Alternatively, virgin queens may produce their own fertility signals, and simultaneously degrade them using the GSTs and Cytochrome P450s, hence permitting them to avoid aggression from the workers yet be able to rapidly increase levels of fertility signals when orphaned.

We also identified three upregulated genes putatively related to olfactory signals, two chemo-sensory proteins (CSPs) and one odorant binding protein (OBP). The CSPs and OBP may play the roles of carrier proteins (Pelosi et al. 2005; Gotzek & Ross 2007) possibly involved in the production of reproductive status signals. Interestingly, the gene with the highest sequence similarity to the OBP is Gp-9, a gene that is linked to odour differences between queens (Keller & Ross 1998; Gotzek & Ross 2007) and to the selective execution of queens which lack the small b allele at this locus in multiplequeen colonies of S. invicta (Keller & Ross 1998; Ross & Keller 1998; Krieger & Ross 2002; Ross & Keller 2002; Gotzek & Ross 2009). The upregulated OBP could similarly be involved in the production of a qualitative signal by virgin queens.

Genes known to be involved in reproductive development in social insects

The level of JH increases with the onset of reproduction in many female insects. In particular, high JH titres have been linked to reproductive dominance in bumble bees as well as in Polistes wasps, but not in honey bees where JH has been shown to regulate the labour tasks between workers (reviewed in Robinson & Vargo 1997). After orphaning young S. invicta queens, JH synthesis rate increases and JH body content peaks prior to wing shedding (Brent & Vargo 2003; see also Fig. 1). The ectopic application of synthetic JH to virgin queens leads to wing shedding even if the mother queen is present (Vargo & Laurel 1994), whereas applying an inhibitor of JH synthesis represses wing shedding in orphaned virgin queens (Burns et al. 2002). The fact that JH level increases after orphaning is consistent with our findings that four genes putatively involved in JH degradation are downregulated after orphaning. Indeed, downregulation of these genes should lead to reduced JH degradation and thus to increased JH levels. Our data also imply that JH degradation genes are highly expressed before orphaning, and thus that JH is already being produced and simultaneously degraded before orphaning. Thus, maintenance of low JH levels in virgin queens prior to orphaning may be due to the simultaneous production and degradation of JH. This has also been suggested to occur in bumble bee workers by Bloch et al. (2000) who found that the rate of in vitro JH synthesis does not reliably indicate haemolymph JH titres. Such dual control of JH titre by simultaneous production and degradation of JH is known to exist from studies in solitary insects (de Kort & Granger 1981; Tobe & Stay 1985).

Beyond the role of JH, two small-scale studies identified genes associated with reproductive differences in ants. In S. invicta queens, participation in a mating flight triggers wing shedding and reproductive development (Tschinkel 2006) and leads to the upregulation of at least seven genes (Tian et al. 2004). One of these genes, Striated Muscle Activator of Rho Signaling (STARS), was also significantly upregulated in our study 6 and 24 h after orphaning. Five of the remaining genes, Vitellogenin-1, Vitellogenin-2, Yellow-1, Yellow-2 and Abaecin were more highly expressed after orphaning, although not significantly so. A study in the black garden ant Lasius niger identified seven genes more highly expressed in mature queens than in workers (Gräff et al. 2007). While none of these genes showed significant expression differences in our study, the mean expression level for four of them was nonsignificantly higher after orphaning in S. invicta. The remaining three genes were, respectively, absent from the S. invicta microarray, similarly expressed or had nonsignificantly lower mean expression levels after orphaning.

Genes that are putatively proteasomal

Genes with similarity to proteasomal genes were highly overrepresented among the genes upregulated after orphaning. Proteasomes are responsible for degrading unneeded proteins. The proteasomal genes could be involved in degrading wing muscle tissue or storage proteins such as hexamerins and vitellogenins that would liberate amino acids that can be used for reproductive development. Alternatively, the increased proteasomal activity after orphaning may trigger changes in gene expression or cellular proliferation via the respective degradation of transcriptional repressors or specific cyclins. Both possibilities are coherent with the overrepresentation of proteasomal genes among the genes that we identified as being upregulated after orphaning in ant queens and also after mating in bees and mosquitoes. This indicates that the role of proteasomal genes during the onset of reproductive development may be evolutionarily conserved. Furthermore, we detected significant downregulation of a gene with similarity to Cellular Repressor of E1A-stimulated Genes 1 (CREG1) after orphaning. CREG1 has been shown to inhibit growth in human cancer cells and to inhibit apoptosis of human muscle cells (Han et al. 2006). The downregulation and degradation of this gene in virgin fire ant queens may similarly induce proliferation of ovarian tissue or the apoptosis of wing muscle cells.

Genes putatively involved in protein transport

Genes sharing sequence identity with those involved in protein transport were highly overrepresented among the genes upregulated after orphaning. Proteins need to be shuttled between intracellular compartments for posttranslational modifications as well as signal transduction. Protein transportation is also essential for communication between cells via the secretion and uptake of proteins (Lodish et al. 2000). The upregulation of putative protein transport genes in orphaned fire ant queens could be involved in changes in neuronal activity (Buckley et al. 2000) as a response to orphaning. Alternatively, they may be involved in ovarian development.

Genes putatively involved in transcriptional changes and chromatin remodelling

Three lines of evidence indicate that major transcriptomic and epigenetic changes are taking place after orphaning in virgin fire ant queens. First, the upregulated genes include two putative RNA polymerase subunits as well as a putative Mediator complex subunit involved in protein-coding gene transcription (Björklund & Gustafsson 2005). Second, a Zinc finger transcription factor domain containing gene is downregulated, while STARS and a RING finger transcription factor domain containing gene are upregulated. STARS may induce wing muscle degradation as previously suggested (Tian et al. 2004). Finally, genes similar to Chromobox Homolog protein 1 and Nucleoplasmin-like protein are upregulated after orphaning. Both are important for chromatin remodelling (Lomberk et al. 2006; Frehlick et al. 2007). Some or all of these gene expression changes could be related to the postorphaning increases in ovarian development and egg production (Vargo & Laurel 1994; Vargo 1999).

Conclusion

This study represents the first genome-wide survey of gene expression changes in subordinate animals immediately following the sudden loss of the dominant individual. We identified 297 genes differentially expressed within 24 h of orphaning in virgin S. invicta queens. Many of the observed gene expression changes are consistent with previous knowledge about the physiological changes in virgin queens after orphaning, and some genes related to the onset of reproductive development appear to be conserved across species from ants to bees and even mosquitoes. Additionally, we detected several genes possibly required for the perception or production of olfactory signals. These genes may play roles in triggering the onset of reproductive development in virgin queens or in signalling reproductive status to nestmates. Finally, we found evidence for activation of genes putatively involved in muscle degradation and ovarian development. However, much work remains to truly understand the molecular-genetic cascades of events involved in the competition for reproductive dominance between virgin queens. It will be particularly fascinating to understand the evolutionary pressures acting upon different genes involved in this process. A further challenge will be identifying the basis by which workers make decisions regarding which competing queens to execute and which to keep.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kenneth G Ross and Dietrich Gotzek for help collecting ants, Micah Gardner for help feeding the ants, Christine LaMendola and the Lausanne DNA Array Facility for support with molecular work, Darlene Goldstein, Frédéric Schütz and the Bioconductor mailing list for statistical advice, Rob L Hammond, Julien Roux, Joel Meunier and the Keller, Chapuisat and Robinson-Rechavi laboratories for stimulating discussions, and Kenneth G Ross, D. DeWayne Shoemaker, Aurélie Bonin and three anonymous referees for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this manuscript. This work was funded by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation and the Rectorate of the University of Lausanne.

References

-

Alaux C, Le Conte Y, Adams HA et al. (2009) Regulation of brain gene expression in honey bees by brood pheromone. Genes, Brain and Behavior, 8, 309–319.

-

Alexa A, Rahnenführer J, Lengauer T (2006) Improved scoring of functional groups from gene expression data by decorrelating GO graph structure. Bioinformatics, 22, 1600– 1607.

-

Ashburner M, Ball CA, Blake JA et al. (2000) Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genetics, 25, 25–29.

-

Barker JF (1979) Endocrine basis of wing casting and flight muscle histolysis in the red imported fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Experientia, 35, 552–554.

-

Barrett T, Troup DB, Wilhite SE et al. (2009) NCBI GEO: archive for high-throughput functional genomic data. Nucleic Acids Research, 37, D885–890.

-

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B, 57, 289–300.

-

Björklund S, Gustafsson CM (2005) The yeast mediator complex and its regulation. Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 30, 240–244.

-

Bloch G, Borst DW, Huang ZY, Robinson GE, Cnaani J, Hefetz A (2000) Juvenile hormone titers, juvenile hormone biosynthesis, ovarian development and social environment in Bombus terrestris. Journal of Insect Physiology, 46, 47–57.

-

Bourke AFG, Franks NR (1995) Social Evolution in Ants. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

-

Brent C, Vargo EL (2003) Changes in juvenile hormone biosynthetic rates and whole body content in maturing virgin queens of Solenopsis invicta. Journal of Insect Physiology, 49, 967–974.

-

Buckley KM, Melikian HE, Provoda CJ, Waring MT (2000) Regulation of neuronal function by protein trafficking: a role for the endosomal pathway. Journal of Physiology, 525, 11–19.

-

Burmeister SS, Jarvis ED, Fernald RD (2005) Rapid behavioral and genomic responses to social opportunity. PLoS Biology, 3, e363.

-

Burns SN, Teal PEA, Vander Meer RK, Nation J, Vogt JT (2002) Identification and action of JH III from sexually mature alate females of the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Journal of Insect Physiology, 48, 357–365.

-

Burns SN, Vander Meer RK, Teal PEA (2007) Mating flight activity as dealation factors for red imported fire ant (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) female alates. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 100, 257–264.

-

Dietemann V, Pflugfelder J, Hartel S, Neumann P, Crewe RM (2006) Social parasitism by honeybee workers (Apis mellifera capensis esch.): evidence for pheromonal resistance to host queen’s signals. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 60, 785– 793.

-

Feyereisen R (1999) Insect P450 enzymes. Annual Review of Entomology, 44, 507–533.

-

Fletcher DJC, Blum MS (1981) Pheromonal control of dealation and oogenesis in virgin queen fire ants. Science, 212, 73–75.

-

Fletcher DJC, Blum MS (1983) Regulation of queen number by workers in colonies of social insects. Science, 219, 312–314.

-

Fletcher DJC, Cherix D, Blum MS (1983) Some factors influencing dealation by virgin queen fire ants. Insectes Sociaux, 30, 443–454.

-

Frehlick LJ, Eirín-López JM, Ausió J (2007) New insights into the nucleophosmin/nucleoplasmin family of nuclear chaperones. Bioessays, 29, 49–59.

-

Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM et al. (2004) Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biology, 5, R80.

-

Gotzek D, Ross KG (2007) Genetic regulation of colony social organization in fire ants: an integrative overview. The Quarterly Review of Biology, 82, 201–226.

-

Gotzek D, Ross KG (2009) Current status of a model system: the gene Gp-9 and its association with social organization in fire ants. PLoS One, 4, e7713.

-

Gräff J, Jemielity S, Parker JD, Parker KM, Keller L (2007) Differential gene expression between adult queens and workers in the ant Lasius niger. Molecular Ecology, 16, 675– 683.

-

Grozinger CM, Sharabash NM, Whitfield CW, Robinson GE (2003) Pheromone-mediated gene expression in the honey bee brain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 100, 14519–14525.

-

Grozinger CM, Fan Y, Hoover SER, Winston ML (2007) Genome-wide analysis reveals differences in brain gene expression patterns associated with caste and reproductive status in honey bees (Apis mellifera). Molecular Ecology, 16, 4837–4848.

-

Haider S, Ballester B, Smedley D, Zhang J, Rice P, Kasprzyk A (2009) Biomart central portal – unified access to biological data. Nucleic Acids Research, 37, W23–27.

-

Han YL, Xu HM, Deng J et al. (2006) Over-expression of the cellular repressor of E1A-stimulated genes inhibits the apoptosis of human vascular smooth muscle cells in vitro. Sheng Li Xue Bao (Acta physiologica Sinica), 58, 324–330.

-

Holmes MM, Rosen GJ, Jordan CL, de Vries GJ, Goldman BD, Forger NG (2007) Social control of brain morphology in a eusocial mammal. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 104, 10548–10552.

-

Jouvenaz DP, Allen GE, Banks WA, Wojcik DP (1977) A survey for pathogens of fire ants, Solenopsis spp., in the southeastern United States. The Florida Entomologist, 60, 275– 279.

-

Kauffmann A, Gentleman R, Huber W (2009) arrayQualityMetrics – a bioconductor package for quality assessment of microarray data. Bioinformatics, 25, 415–416.

-

Keller L (1993) Queen Number and Sociality in Insects. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

-

Keller L, Reeve HK (1994) Partitioning of reproduction in animal societies. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 9, 98–102.

-

Keller L, Ross KG (1998) Selfish genes: a green beard in the red fire ant. Nature, 394, 573–575.

-

Kendziorski C, Irizarry RA, Chen KS, Haag JD, Gould MN (2005) On the utility of pooling biological samples in microarray experiments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 102, 4252–4257.

-

Kocher SD, Richard FJ, Tarpy DR, Grozinger CM (2008) Genomic analysis of post-mating changes in the honey bee queen (Apis mellifera). BMC Genomics, 9, 232.

-

de Kort CAD, Granger NA (1981) Regulation of the juvenile hormone titer. Annual Review of Entomology, 26, 1–28.

-

Krieger MJB, Ross KG (2002) Identification of a major gene regulating complex social behavior. Science, 295, 328–332.

-

Lawniczak MKN, Begun DJ (2004) A genome-wide analysis of courting and mating responses in Drosophila melanogaster females. Genome, 47, 900–910.

-

Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky SL, Matsudaira P, Baltimore D, Darnell J (2000) Molecular Cell Biology. W.H. Freeman and Company, New York.

-

Lomberk G, Wallrath L, Urrutia R (2006) The heterochromatin protein 1 family. Genome Biology, 7, 228.

-

Maibeche-Coisne M, Nikonov A, Ishida Y, Jacquin-Joly E, Leal W (2004) Pheromone anosmia in a scarab beetle induced by in vivo inhibition of a pheromone-degrading enzyme. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 101, 11459–11464.

-

McGraw LA, Gibson G, Clark AG, Wolfner MF (2004) Genes regulated by mating, sperm, or seminal proteins in mated female Drosophila melanogaster. Current Biology, 14, 1509– 1514.

-

de Montellano PRO (2005) Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publisher, New York.

-

Neumann P, Hepburn HR, Radloff SE (2000) Modes of worker reproduction, reproductive dominance and brood cell construction in queenless honeybee (Apis mellifera l.) colonies. Apidologie, 31, 479–486.

-

Pelosi P, Calvello M, Ban L (2005) Diversity of odorant-binding proteins and chemosensory proteins in insects. Chemical Senses, 30, i291–i292.

-

Pereboom JJM, Jordan WC, Sumner S, Hammond RL, Bourke AFG (2005) Differential gene expression in queen–worker caste determination in bumble-bees. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 272, 1145–1152.

-

Remm M, Storm CEV, Sonnhammer ELL (2001) Automatic clustering of orthologs and in-paralogs from pairwise species comparisons. Journal of Molecular Biology, 314, 1041–1052.

-

Renn SCP, Aubin-Horth N, Hofmann HA (2004) Biologically meaningful expression profiling across species using heterologous hybridization to a cDNA microarray. BMC Genomics, 5, 42.

-

Renn SCP, Aubin-Horth N, Hofmann HA (2008) Fish and chips: functional genomics of social plasticity in an African cichlid fish. Journal of Experimental Biology, 211, 3041–3056.

-

Roberge C, Blanchet S, Dodson JJ, Guderley H, Bernatchez L (2008) Disturbance of social hierarchy by an invasive species: a gene transcription study. PLoS One, 3, e2408.

-

Robinson GE, Vargo EL (1997) Juvenile hormone in adult eusocial Hymenoptera: gonadotropin and behavioral pacemaker. Archives of Insect Biochemistry and Physiology, 35, 559–583.

-

Rogers DW, Whitten MMA, Thailayil J, Soichot J, Levashina EA, Catteruccia F (2008) Molecular and cellular components of the mating machinery in Anopheles gambiae females. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 105, 19390–19395.

-

Roseler P (1991) Social and reproductive dominance among ants. Naturwissenschaften, 78, 114–120.

-

Roseler P, Roseler I, Strambi A, Augier R (1984) Influence of insect hormones on the establishment of dominance hierarchies among foundresses of the paper wasp, Polistes gallicus. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 15, 133–142.

-

Ross KG (1997) Multilocus evolution in fire ants: effects of selection, gene flow and recombination. Genetics, 145, 961– 974.

-

Ross KG, Keller L (1998) Genetic control of social organization in an ant. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA, 95, 14232–14237.

-

Ross KG, Keller L (2002) Experimental conversion of colony social organization by manipulation of worker genotype composition in fire ants (Solenopsis invicta). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 51, 287–295.

-

Ross KG, Shoemaker DD (2008) Estimation of the number of founders of an invasive pest insect population: the fire ant Solenopsis invicta in the USA. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 275, 2231–40.

-

Ross KG, Vargo EL, Keller L, Trager JC (1993) Effect of a founder event on variation in the genetic sex-determining system of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Genetics, 135, 843– 854.

-

Shoemaker DD, DeHeer C, Krieger MJB, Ross KG (2006) Population genetics of the invasive fire ant Solenopsis invicta in the U.S.A. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 99, 1213–1233.

-

Smyth GK (2004) Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology, 3, Article 3.

-

Smyth GK, Speed T (2003) Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods, 31, 265–273.

-

Smyth GK, Thorne N, Walter JW (2005) limma: Linear Models for Microarray Data User’s Guide.

-

Solomon NG, French JA (1997) Cooperative Breeding in Mammals. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K.

-

The Honey Bee Genome Sequencing Consortium (2006) Insights into social insects from the genome of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Nature, 443, 931–949.

-

The R Development Core Team (2007) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

-

Tian H, Vinson SB, Coates C (2004) Differential gene expression between alate and dealate queens in the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta buren (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 34, 937–949.

-

Tobe SS, Stay B (1985) Structure and regulation of the corpus allatum. Advances in Insect Physiology, 18, 305–432.

-

Toth AL, Varala K, Newman TC et al. (2007) Wasp gene expression supports an evolutionary link between maternal behavior and eusociality. Science, 318, 441–444.

-

Tschinkel WR (2006) The Fire Ants. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

-

Vander Meer RK, Glancey BM, Lofgren CS, Glover A, Tumlinson JH, Rocca J (1980) The poison gland of the red imported fire ant queens: source of a pheromone attractant. Annals of the Entomological Society of America, 73, 609–612.

-

Vargo EL (1999) Reproductive development and ontogeny of queen pheromone production in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Physiological Entomology, 24, 370–376.

-

Vargo EL, Hulsey CD (2000) Multiple glandular origins of queen pheromones in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Journal of Insect Physiology, 46, 1151–1159.

-

Vargo EL, Laurel M (1994) Studies on the mode of action of a queen primer pheromone of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Journal of Insect Physiology, 40, 601–610.

-

Vargo EL, Porter SD (1993) Reproduction by virgin fire queen ants in queenless colonies: comparative study of three taxa (S. richteri, hybrid S. invicta/richteri, S. geminata) (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Insectes Sociaux, 40, 283–293.

-

Voigt C, Leitner S, Gahr M (2007) Socially induced brain differentiation in a cooperatively breeding songbird. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 274, 2645–2651.

-

Wang J, Jemielity S, Uva P, Wurm Y, Gräff J, Keller L (2007) An annotated cDNA library and microarray for large-scale gene-expression studies in the ant Solenopsis invicta. Genome Biology, 8, R9.

-

Wang J, Ross KG, Keller L (2008) Genome-wide expression patterns and the genetic architecture of a fundamental social trait. PLoS Genetics, 4, e1000127.

-

Weil T, Korb J, Rehli M (2009) Comparison of queen-specific gene expression in related lower termite species. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 26, 1841–1850.

-

White SA, Nguyen T, Fernald RD (2002) Social regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Journal of Experimental Biology, 205, 2567–2581.

-

Wilson EO (1971) The Insect Societies. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

-

Wurm Y, Uva P, Ricci F et al. (2009) Fourmidable: a database for ant genomics. BMC Genomics, 10, 5.

This work is part of Y. Wurm’s PhD thesis under the supervision of L. Keller. Y. Wurm and J. Wang use genetic tools to study the social lives of ants. L. Keller works on various aspects of evolutionary ecology such as reproductive skew, sex allocation, caste determination as well as the molecular basis of aging and behaviour in ants.

Supporting Information

Table S1 List and annotations of all fire ant genes significantly upregulated for at least one of the following comparisons: 6h vs 0h, 24h vs 6h, 24h vs 0h. Some genes are significant according to multiple microarray clones

Table S2 List and annotations of all fire ant genes significantly downregulated for at least one of the following comparisons: 6h vs 0h, 24h vs 6h, 24h vs 0h. Some genes are significant according to multiple microarray clones

Table S3 List and annotations of all fire ant genes significantly upregulated for at least one of the following comparisons: 6h vs 0h, 24h vs 6h, 24h vs 0h and also significantly higher in brains of honey bee queens than reproductive workers

Table S4 List and annotations of all fire ant genes significantly upregulated for at least one of the following comparisons: 6h vs 0h, 24h vs 6h, 24h vs 0h and also significantly upregulated after mating in honey bee queens

Table S5 List and annotations of all fire ant genes significantly upregulated for at least one of the following comparisons: 6h vs 0h, 24h vs 6h, 24h vs 0h and also significantly upregulated ins Anopheles gambiae females in response to mating according to ectorbase gene expression data

Fig. S1 Graphical representation of microarray hybridizations. The unit of biological replication is the colony; each pool of five queens was hybridized to two different microarrays. Each vertice represents an amplified RNA sample and each edge represents a microarray hybridization (a total of 3 × 8 = 24 hybridizations were conducted). Cy3-labeled samples are at the tails and Cy5-labeled samples are at the heads of arrows.

Data S1 Genepix GPR files and normalized log2 (Cy5/Cy3) ratios are found in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (Barrett et al. 2009) under accession number GSE19721.

Please note: Wiley-Blackwell are not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting materials supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.

-

MEC_4561_sm_fig.pdf – Supporting info item, (.PDF, 64.6 KB)

-

MEC_4561_sm_table1.xls – Supporting info item, (.XLS, 102.5 KB)

-

MEC_4561_sm_table2.xls – Supporting info item, (.XLS, 70.5 KB)

-

MEC_4561_sm_table3.xls – Supporting info item, (.XLS, 26 KB)

-

MEC_4561_sm_table4.xls – Supporting info item, (.XLS, 27 KB)

-

MEC_4561_sm_table5.xls – Supporting info item, (.XLS, 33.5 KB)

Please note: The publisher is not responsible for the content or functionality of any supporting information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing content) should be directed to the corresponding author for the article.