Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 16 November 2020

Evolution: The Legacy of Endosymbiosis in Ants

Raphaella Jackson, Lee M. Henry, Yannick Wurm

Current Biology (2020) R1385

Summary

A symbiotic partnership with Blochmannia bacteria is thought to underpin the ecological success of carpenter ants. Disentangling the molecular interactions between the mutualistic partners supports an old hypothesis that many other ants also had similar symbioses and lost them.

Main Text

“It is more natural to explain the findings in the ants with the assumption that the bacterial symbiosis was originally more widespread than it is today, and that the subsequent loss could still be seen in vestigial phenomena during embryonic development.” Margarete Lilienstern (1932)

Endosymbiotic relationships can be permanent, as is the case for the mitochondria or the chloroplast within the eukaryotic cell. However, such relationships may also break down leaving traces of their existence. Around 1930, Margarete Lilienstern’s examinations of Formica ants highlighted what she felt were traces of a lost bacterial symbiosis, with anatomical signatures of bacteriocytes — specialized host cells that house endosymbionts — that no longer developed [1]. Bacteriocytes occur in a wide range of insects, in particular, those that specialize on nutritionally unbalanced diets, such as blood or plant sap. The acquisition of nutrient provisioning symbionts is therefore a key innovation that has enabled insects to diversify in ecological niches that they would otherwise be excluded from [2]. One of the earliest documented nutritional endosymbioses in insects is found in Camponotus carpenter ants. In the 1880s, Friederich Blochmann identified conspicuously differentiating ‘plasma rodlets’ in the development of these ants, which were later recognized as symbiotic bacteria housed in bacteriocytes [3]. The symbionts provide essential amino acids to the ants, which improves colony health when proteins are scarce [4]. In doing so, the Blochmannia bacteria may underlie the success of Camponotus ants to thrive in arboreal environments. Indeed, by relaxing their direct need for nitrogen, these ants can feed predominantly on plant-derived resources such as extrafloral nectars and the honey-dew of sucking insects [4,5]. Detailed microscopy work by Paul Buchner and others later highlighted the complexity of forming bacteriocytes and vertically transmitting bacteria. However, until now the molecular–genetic interactions that enable the complex development of host–symbiont relationships have remained obscure. A new study by Ab. Matteen Rafiqi, Arjuna Rajakumar and Ehab Abouheif [6] provides fascinating insight into how the co-opting of old cellular machinery can support new processes which underpin the intimate association between bacteria and host.

Disentangling the Developmental Basis of an Obligate Symbiosis

By combining comparative phylogenomics with cytogenetics, gene and bacterial knockouts, and expression analyses, Rafiqi and colleagues [6] identify fundamental differences in embryogenesis between Camponotus ants and other insects including wasps, flies and other species of ant. The germplasm — a portion of maternal cytoplasm that specifies the germline and orientation of the developing embryo — is ancestrally localized to a specific area of the freshly laid embryo. However, in Camponotus floridanus, the mRNAs and proteins that localize to the germplasm also localize to three additional zones. Rafiqi and colleagues [6] show how each of the four zones plays a distinct role in Blochmannia’s developmental integration and how Blochmannia and Camponotus both contribute to this process.

The hox genes AbdominalA and Ultrabithorax are normally involved in developmental differentiation of body segments. However, in Camponotus, these genes additionally coordinate the positions of the four zones. Reducing the expression of the two hox genes using RNA interference affects the localizations of all four zones, and consequently leads to incorrect placement or absence of bacteriocytes and Blochmannia. Crucially, the four distinct embryonic zones form even when Blochmannia is absent. However, when it is present, Blochmannia ensures that each zone is functionally distinct by regulating Camponotus gene expression in zone-specific manners. This surprising result demonstrates that symbionts shape their hosts’ development to facilitate their own integration — Camponotus sets the stage, but Blochmannia leads.

To understand how the interplay between host and symbiont emerged, Rafiqi and colleagues [6] examined whether five traits essential for the symbiosis are shared with other ants. They found that several of the trait characteristics are unique to the Camponotus–Blochmannia association. However, related ant lineages that lack bacteriocyte-associated endosymbionts share some of these characteristics. Two interpretations of this pattern are reasonable: formicine ants are genetically predisposed to form bacteriocytes, or endosymbioses were once widespread in this taxon but have been subsequently lost.

Rafiqi and colleagues [6] support the first hypothesis by showing that the multiple distinct embryonic zones involved in symbiont integration already existed before the Blochmannia symbiosis in carpenter ants. They further show that anterior positioning of the embryo within the egg may be ancestral to all formicine ants. The types of selective pressures that could lead to such developmental changes are unclear. However, the authors argue that the ancestral developmental changes made it easier for bacteriocyte-associated symbioses to evolve. In line with this idea, two additional genera within the Formicinae subfamily also have bacteriocyte-associated endosymbionts. The bacteria acquired by these different ant lineages are taxonomically distinct, suggesting that the symbioses may have evolved independently.

Remnants of a Widespread Symbiosis in Ants?

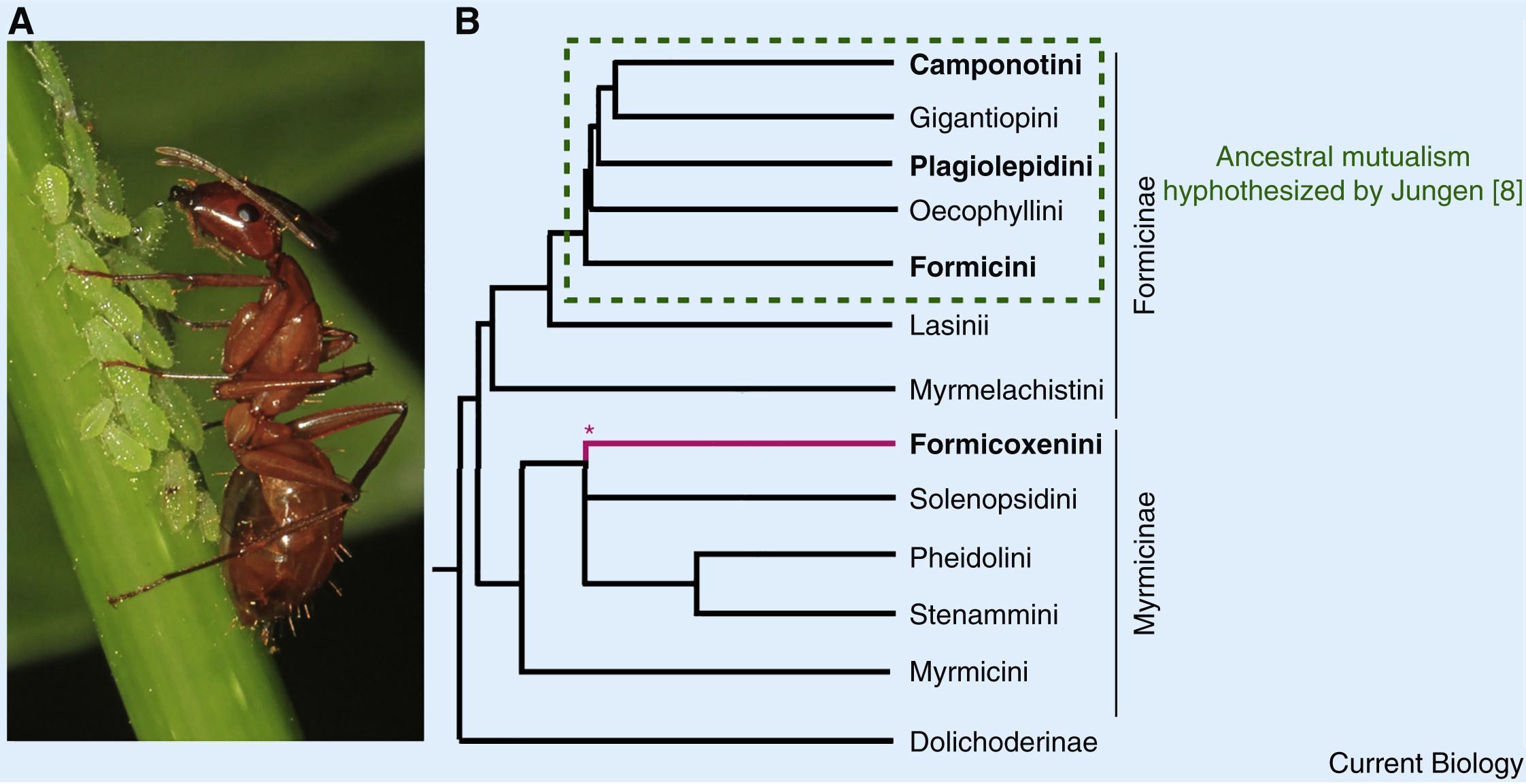

Lillienstern and later Buchner hypothesized that bacteriocyte-associated endosymbioses were once more widespread in ants than those currently observed [1,7]. This belief was further supported by Hans Jungen’s finding of bacteriocytes in Plagiolepis ants, which, he claimed, developed identically to those in Formica. His interpretation of this result was that an ancestral symbiosis likely existed in the common ancestor of all of these species, potentially spanning most Formicinae (Figure. 1) [8]. This does not detract from the new insights of Rafiqi and colleagues [6] but does offer an alternative interpretation to their findings, whereby an ancestral symbiosis was lost in lineages other than Camponotus, Formica and Plagiolepis. The distinct bacterial taxa now present in the different ant lineages could be the products of symbiont replacements through the type of symbiont-turnover that occurred in mealybugs [9]. In this case, the developmental traits Camponotus shares with species that lack symbioses could be vestigial remnants of the ancestral symbiosis.

Figure.1 Endosymbiont mutualisms in ants

(A) A Camponotus worker tends aphids (photo: Judy Gallagher/Flickr CC BY 2.0). (B) The bacteriocyte-associated symbioses present in four extant ant lineages may have evolved independently. Alternatively, the Formicinae subfamily of ants ancestrally had a bacteriocyte-associated mutualism that was subsequently lost (Jungen; [8]). Phylogeny derived from [6]; ∗branch placement based on [13].

Sequencing the genome of Cardiocondyla obscurior [10] led to the discovery of a fourth bacteriocyte-associated symbiosis in ants, albeit in the more distantly related Myrmicinae subfamily [11]. This is the only known bacteriocyte-associated symbiosis in this large subfamily; therefore, it likely evolved independently from those seen in the Formicinae. Compared to other insect families, relatively few ant lineages have been investigated for symbioses. New genome sequencing efforts [12] and cytogenetic studies across diverse ant lineages will likely reveal previously unknown symbiotic associations and should help clarify how widespread any ancestral endosymbiosis could have been.

Outside of Blochmannia, we know little about how endosymbionts contribute to the success of their typically omnivorous ant hosts. Certainly, niches and environments can change and reduce the host’s needs for particular nutritional supplementation. In addition, vertical transmission leads to the gradual erosion of an endosymbiont’s genome, which can reduce the ability to synthesize nutrients that are important for maintaining a symbiosis [2]. Thus, despite the efforts of both partners in constructing and maintaining a long-term relationship, the symbiont can become irrelevant, and the relationship too can come to an end. In line with this, Lilienstern showed that bacteriocyte-associated symbiosis was lost in some species of the Formica genus. It is tempting to consider whether Rafiqi and Jungen’s interpretations may both be true: an ancestral symbiosis could have been completely lost, with its vestigial remains creating a predisposition for parallel emergence of new bacteriocyte-associated symbioses in Camponotus, Formica, and Plagiolepis.

References

-

Lilienstern M. Beiträge zur Bakteriensymbiose der Ameisen. Z. Morph. u. Okol. Tiere. 1932; 26: 110-134

-

Moran N.A. Telang A. Bacteriocyte-associated symbionts of insects. Bioscience. 1998; 48: 295-304

-

Blochmann F. Über das Vorkommen bakterienähnlicher Gebilde in den Geweben und Eiern verschiedener Insekten. Zentbl. Bakteriol. 1887; 11: 234-249

-

Feldhaar H. Straka J. Krischke M. Berthold K. Stoll S. Mueller M.J. Gross R. Nutritional upgrading for omnivorous carpenter ants by the endosymbiont Blochmannia. BMC Biol. 2007; 5: 48

-

Blüthgen N. Gebauer G. Fiedler K. Disentangling a rainforest food web using stable isotopes: dietary diversity in a species-rich ant community. Oecologia. 2003; 137: 426-435

-

Rafiqi A.M. Rajakumar A. Abouheif E. Origin and elaboration of a major evolutionary transition in individuality. Nature. 2020; 585: 239-244

-

Buchner P. Endosymbiosis of Animals with Plant Microorganisms. Interscience Publishers, 1965

-

Jungen H. Endosymbionten bei Ameisen. Insectes Sociaux. 1968; 15: 227-232

-

Husnik F. McCutcheon J.P. Repeated replacement of an intrabacterial symbiont in the tripartite nested mealybug symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016; 113: E5416-E5424

-

Schrader L. Kim J.W. Ence D. Zimin A. Klein A. Wyschetzki K. Weichselgartner T. Kemena C. Stökl J. Schultner E. et al. Transposable element islands facilitate adaptation to novel environments in an invasive species. Nat. Commun. 2014; 5: 5495

-

Klein A. Schrader L. Gil R. Manzano-Marín A. Flórez L. Wheeler D. Werren J.H. Latorre A. Heinze J. Kaltenpoth M. et al. A novel intracellular mutualistic bacterium in the invasive ant Cardiocondyla obscurior. ISME J. 2015; 10: 376-388

-

Favreau E. Martínez-Ruiz C. Santiago L.R. Hammond R.L. Wurm Y. Genes and genomic processes underpinning the social lives of ants. Curr. Opin. Insect. Sci. 2018; 25: 83-90

-

Moreau C.S. Bell C.D. Vila R. Archibald S.B. Pierce N.E. Phylogeny of the ants: diversification in the age of angiosperms. Science. 2006; 312: 101-104

Article Info

Identification

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.023

Copyright

© 2020 Elsevier Inc.

User License

ScienceDirect

Access this article on ScienceDirect