Ants, Bees, Genomes & Evolution @ Queen Mary University London

Published: 22 December 2014

Effects of ploidy and sex-locus genotype on gene expression patterns in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta

Mingkwan Nipitwattanaphon, John Wang, Kenneth G. Ross, Oksana Riba-Grognuz, Yannick Wurm, Chitsanu Khurewathanakul and Laurent Keller

Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 2014, Volume 281, Issue 1797

Abstract

Males in many animal species differ greatly from females in morphology, physiology and behaviour. Ants, bees and wasps have a haplodiploid mechanism of sex determination whereby unfertilized eggs become males while fertilized eggs become females. However, many species also have a low frequency of diploid males, which are thought to develop from diploid eggs when individuals are homozygous at one or more sex determination loci. Diploid males are morphologically similar to haploids, though often larger and typically sterile. To determine how ploidy level and sex-locus genotype affect gene expression during development, we compared expression patterns between diploid males, haploid males and females (queens) at three developmental timepoints in Solenopsis invicta. In pupae, gene expression profiles of diploid males were very different from those of haploid males but nearly identical to those of queens. An unexpected shift in expression patterns emerged soon after adult eclosion, with diploid male patterns diverging from those of queens to resemble those of haploid males, a pattern retained in older adults. The finding that ploidy level effects on early gene expression override sex effects (including genes implicated in sperm production and pheromone production/perception) may explain diploid male sterility and lack of worker discrimination against them during development.

1. Introduction

Most sexual organisms have two sexes that can differ greatly in morphology, physiology and behaviour. Sex determination is genetic in many species, and there is great variability in the mechanisms involved [1]. In approximatively 20% of extant animal species sex is determined by the ploidy level of individuals [2]. Under haplodiploidy, unfertilized eggs develop into males, whereas fertilized eggs develop into females. In the honeybee and many other Hymenoptera, sex is determined by the genotype at a single complementary sex-determination (CSD) locus [3,4]. Individuals that are haploid (hemizygous at the CSD (sex) locus) develop into males, whereas diploid individuals heterozygous at the locus develop into females. Remarkably, individuals that are diploid but homozygous at the CSD locus develop into diploid males. Diploid males have been reported in diverse hymenopteran species, although their frequency generally is low.

While Hymenoptera typically are characterized by pronounced morphological and/or physiological differences between males and females, haploid and diploid males generally are very similar in phenotype, with two notable exceptions. First, in all but one studied species [5], diploid males are inviable or sterile [6–9], the latter associated with underdeveloped testes and/or production of diploid sperm [10–15]. Second, studies in ants showed that diploid males are usually larger than their normal haploid counterparts [8,16]. This difference is interesting because ploidy level has been shown to influence cell size and cell proliferation rate in various yeast, plants and animals. Moreover, ploidy level is associated with gene dosage regulation and endopolyploidization that would presumably affect gene expression in many tissues and thus influence overall developmental trajectories [17–22].

Studies in species possessing sex chromosomes have revealed that differences between males and females in size, morphological features and a host of other phenotypic attributes arise mainly because of differences in gene expression profiles between the sexes [23]. The aim of this study was to determine the relative roles of ploidy level and genotype at the sex locus on gene expression patterns associated with sexual development. We used the fire ant Solenopsis invicta as a model species because introduced populations experienced an important bottleneck resulting in a loss of genetic diversity at the sex locus and, consequently, the production of a high proportion of diploid males [8,24]. Diploid males are morphologically similar to but larger than haploid males in this species. Most important, the vast majority of such diploid males lack testes and thus are completely aspermic [14]. Because spermatogenesis occurs exclusively during the pupal stage in ants [25], we compared transcriptomes by using cDNA microarrays [26] of haploid and diploid males in young pupae, 1-day-old adults, and 11-day-old adults. For each of these three key developmental timepoints, we also surveyed diploid queen transcriptomes as a reference to quantify the relative influence of ploidy level and sex on gene expression patterns associated with sexual development (we did not consider workers because they are completely sterile and have highly derived phenotypes). These comparisons are important for understanding the developmental mechanisms underlying the unique morphological and physiological attributes of diploid males, and may shed light on the natural history of diploid male production in colonies of these ants. Finally, because S. invicta workers fail to discriminate against diploid males during rearing despite the large fitness costs to producing such males [24], we compared pupal patterns of expression of genes likely involved in pheromone production/perception to assess whether the workers’ failure to eliminate diploid males might be due to these males being chemically indistinguishable from queens.

2. Material and methods

Additional details and complete methods are in the electronic supplementary material.

(a) Sample collection

Polygyne (multiple-queen) colonies of S. invicta were collected from Athens, Georgia, USA in spring 2009 and reared under standard conditions [27] in Lausanne, Switzerland for two to three months. Social form of each colony was inferred from the presence of multiple inseminated queens in a colony and confirmed by the presence/absence of the Gp-9b allele in workers using a PCR-RFLP assay [28] (colonies with workers bearing the Gp-9b allele invariably are polygyne). Based on previous analyses [29], 15–20% of the polygyne queens in our study population mate with a male sharing one of her alleles at the CSD locus. Therefore, in order to obtain enough families with both haploid and diploid sons as well as queen daughters, we established approximately 80 colony fragments containing a single mated queen. These fragments were reared in the laboratory for four to eight months before sampling haploid males, diploid males and queens. Queens were chosen as the exemplar category of females because they represent the reproductive caste of this sex, in parallel with males (worker fire ants are sterile females with highly reduced morphological phenotypes, including the absence of gonads, genitalic structures and wings).

We collected two individuals of each category at each of three developmental timepoints (young pupa, 1-day-old adult and 11-day-old adult) from each of five fragments that were derived from different source colonies and that were producing at least 10 individuals, yielding a total of 90 sampled individuals. The two individuals of each category from each colony fragment had different Gp-9 genotypes (Gp-9BB or Gp-9Bb for diploid males and females; Gp-9B or Gp-9b for haploid males). Because Gp-9 is a marker of a supergene containing many hundreds of genes in this species [30], individuals with different Gp-9 genotypes potentially could display different gene expression profiles. Examination of the potential effects of Gp-9 genotype on gene expression profiles in males (only male slides analysed) revealed only few differentially expressed genes (electronic supplementary material, table S1), while broader analysis of all categories of individuals revealed no overall effects of Gp-9 genotype on gene expression profiles (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Thus, the Gp-9 genotypes of our samples are not considered further here.

Pupae were collected while entirely white, meaning they had pupated less than 2 days previously. To obtain male and queen adults of known age, we monitored darkly pigmented sexual pupae until they eclosed then immediately transferred them to separate colony fragments with 100–300 workers for 1 day or 11 days before collecting them. Because each individual used for each unique category/Gp-9-genotype/timepoint combination originated from a separate source colony, it represents a genuine biological replicate. Each sampled individual (90 total) was immediately placed in liquid nitrogen before being stored at –80°C. Prior to RNA extraction, the ploidy of all males was determined by determining whether individuals were heterozygous at Gp-9 or any of six polymorphic microsatellites (Sol-11, Sol-20, Sol-36, Sol-42, Sol-49, Sol-55, [31]). Based on the allele frequencies at these loci in USA populations, the probability of diploid males being homozygous at all loci was less than 0.1%.

(b) RNA extraction and cDNA hybridization

RNA samples were extracted from all individuals, except the adult males, using the Qiagen RNeasy kit with slight modification. For adult males, a modified Trizol protocol was used. mRNA was amplified approximately 10–100-fold and hybridized to our cDNA microarrays as described in [32].

(c) Microarray analysis

All samples were compared to a common reference [32] and hybridized on the same batch of microarray slides. Microarray slides were scanned using an Agilent Microarray Scanner and data were analysed using the limma package in R [33]. For statistical analyses, we compared only individuals of the same age-class. We applied empirical Bayes statistics to estimate moderated t-statistics for specific pairwise comparisons, adopting a false positive discovery rate of 1% for all F-tests and each pairwise t-test. We used statistical cutoff rather than an absolute cutoff because small changes could well be significant and important. We performed hierarchical clustering analysis in MeV v. 4.6 [34].

Because most clones of the same gene showed similar expression values (electronic supplementary material, table S3), a given gene was considered as differentially expressed if at least one clone corresponding to it was differentially expressed. The data for all clones are presented in the electronic supplementary material, table S2.

We defined ploidy-specific genes as genes that were significantly differentially expressed between diploid males and haploid males as well as between queens and haploid males (i.e. genes that were upregulated in haploid males compared to both diploid males and queens or genes that were downregulated in haploid males compared to both diploid males and queens). Likewise, sex-specific genes were defined as genes upregulated in queens compared to both diploid and haploid males, or downregulated in queens compared to both diploid and haploid males.

(d) Gene annotation and enrichment test

Because fire ant gene annotations are incomplete, we reevaluated GO annotations for all cDNA sequences present on the microarray using BLAST2GO [35]. In addition, we manually curated gene categories associated with spermatogenesis and pheromone production or perception. Enrichment analyses were done using the TopGO software [36].

(e) Real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR

Expression differences for Exons 4, 5, 6 and 7, as well as the exon splice junction between Exons 4 and 6, of the doublesex (dsx) gene and three control genes (GAPDH, RpL37 and RpS9) for 64 samples were assayed using quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR). qRT-PCR reactions were performed as described in [37]. Statistical analyses (ANOVA) of relative gene expression levels and production of box and whisker plots were performed in R [33].

3. Results

(a) Ploidy level strongly affects gene expression levels in pupae

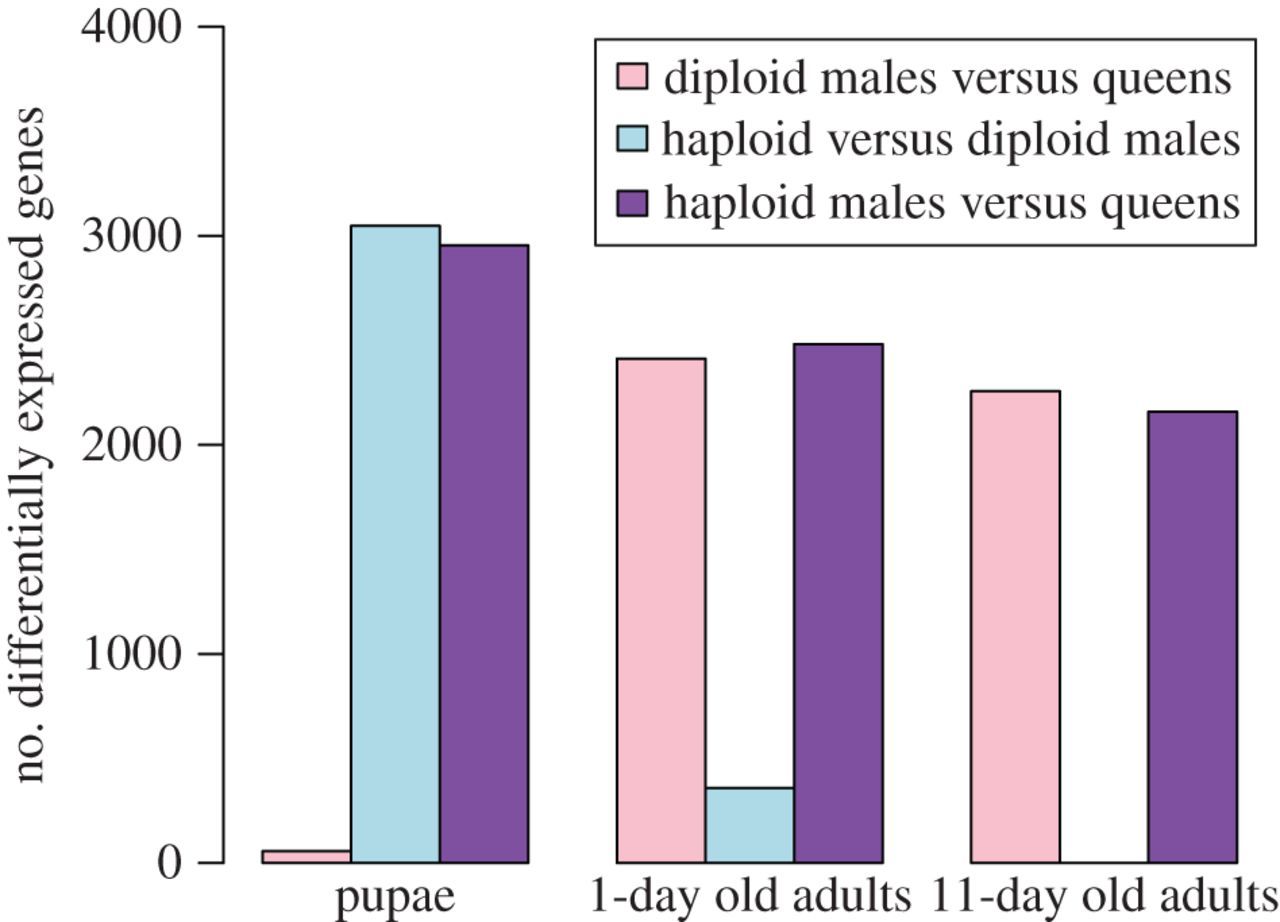

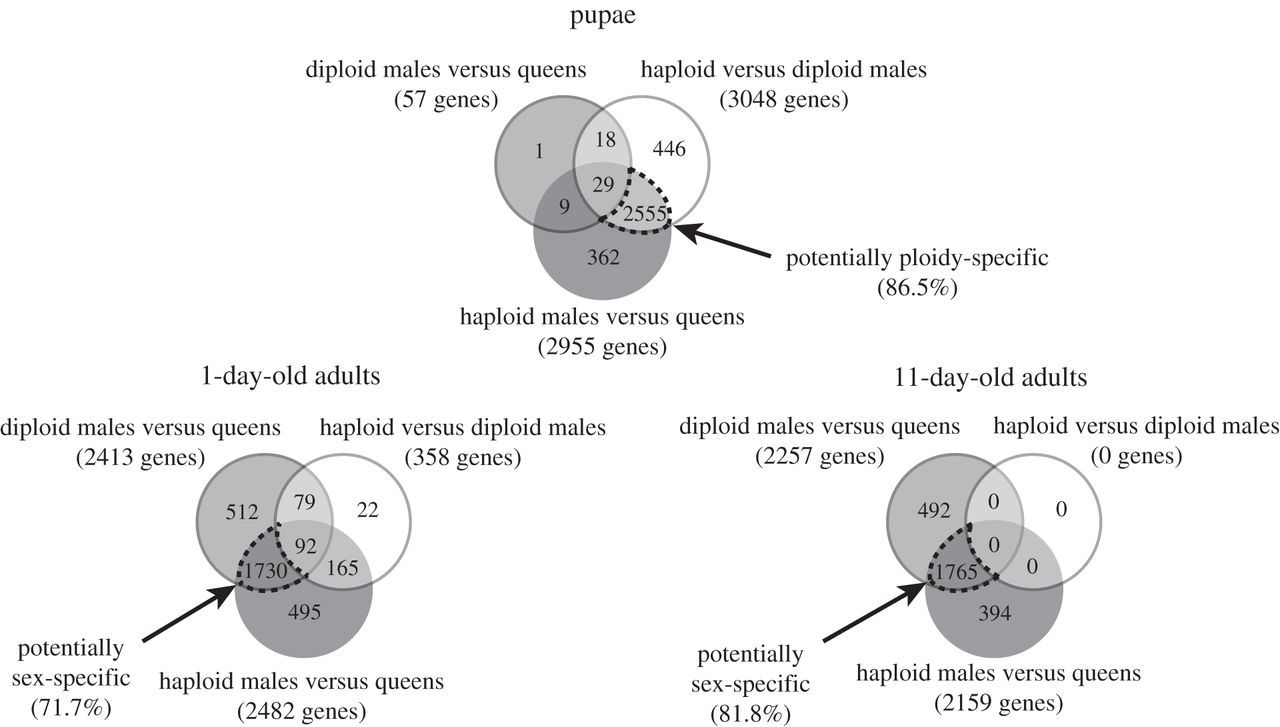

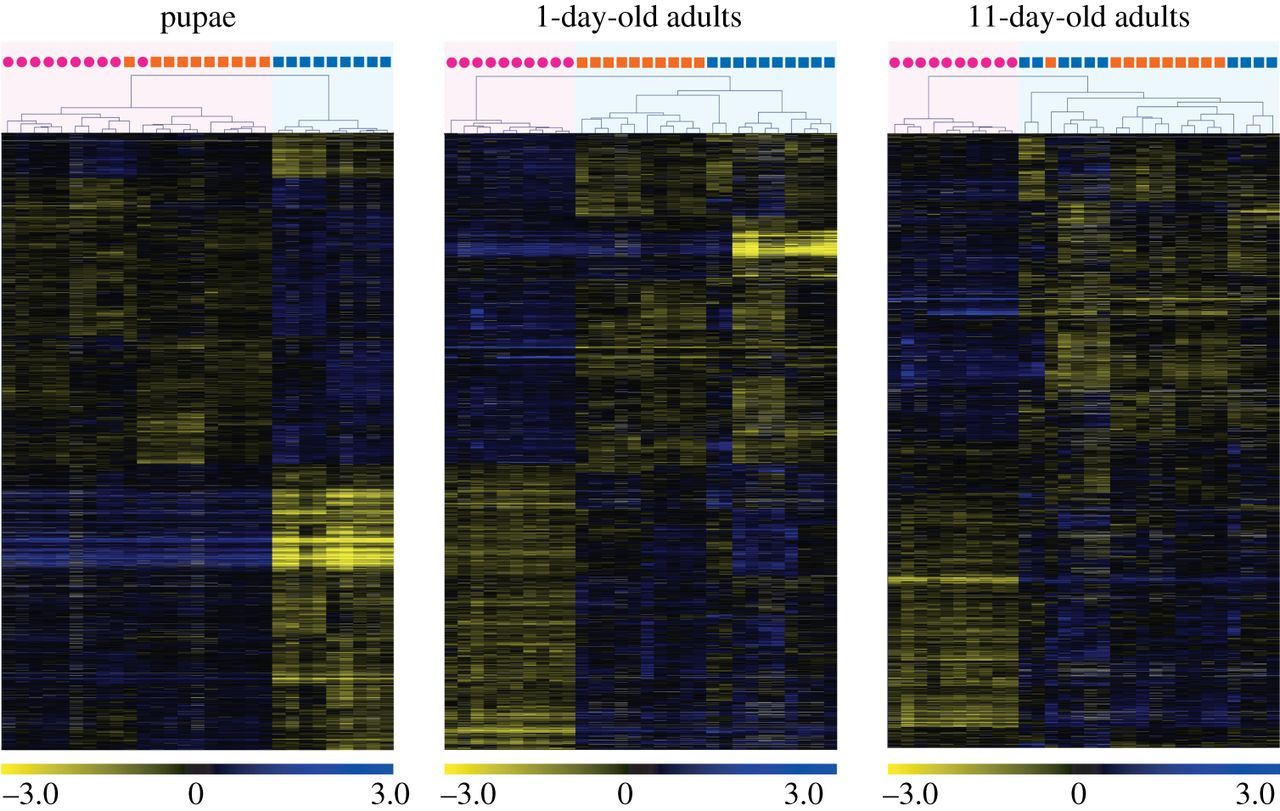

The microarray analyses revealed that ploidy level had a much greater effect than sex on levels of gene expression in pupae (figure 1). While only 57 genes were differentially expressed between diploid males and (diploid) queens, 3048 genes were differentially expressed between diploid and haploid males. Similarly, 2955 genes were differentially expressed between haploid males and queens, which differ in both ploidy and sex phenotype. Moreover, there was extensive overlap between the genes differentially expressed between queens and haploid males and those differentially expressed between diploid and haploid males, with 86.5% of the genes differentially expressed between the former also differentially expressed between the latter (figure 2). The great similarity in expression profiles between pupal queens and diploid males was also revealed by a hierarchical clustering analysis, which yielded two fundamental clusters; all queen and diploid male pupae grouped in one cluster, whereas all haploid male pupae were relegated to a separate cluster (figure 3). This grouping pattern was robust to simultaneous clustering of all samples at all timepoints (electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

Figure 1

Effects of ploidy level and sex on differential gene expression at three developmental timepoints in S. invicta.

Figure 2

Venn diagram with the number of genes differentially expressed between S. invicta individuals of three categories at three developmental timepoints. Dash-outlined intersection areas show the numbers of genes that may be ploidy-specific or sex-specific in their expression and the percentages of total genes on the array that they represent.

Figure 3

Results of hierarchical clustering analysis of gene expression profiles at three developmental timepoints in S. invicta. Individual queens (pink circles), diploid males (orange squares), and haploid males (blue squares) are clustered on the basis of similarity of their profiles (expression values were compared to a common reference) at each timepoint. Each row in the heat map represents a gene and each column represents an individual sample. Colours in the heat maps represent relative levels of expression: blue, highly expressed; yellow, lowly expressed; grey, NA (data not available). Numbers are log2-transformed relative expression levels. Note: gene sets differ across the timepoints (see figure 1).

Enrichment analyses of pupal gene expression revealed that no gene ontology (GO) categories were overrepresented among those few genes that displayed differential expression between diploid males and queens (electronic supplementary material, table S5). For the many genes differentially expressed between diploid and haploid male pupae, GO categories related to ribosomes, translation and protein folding were overrepresented (electronic supplementary material, table S5). The same was true for the plethora of genes differentially expressed between haploid male and queen pupae (electronic supplementary material, table S5), consistent with the substantial overlap in identity of pupal genes differentially expressed between haploid males and queens and between haploid and diploid males.

(b) Sex strongly affects gene expression levels in adults

The relative importance of ploidy level and sex on levels of gene expression changed drastically after adult eclosion. In 1-day-old adults, only 358 genes were differentially expressed between the two types of males, while 2413 and 2482 genes became differentially expressed between queens and diploid or haploid males, respectively (figure 1). About 72% of all genes surveyed were differentially expressed between queens and the males of both ploidy levels (figure 2), that is, are evidently sex-specific in their expression at this age.

The reversal in relative importance of ploidy level and sex in influencing levels of gene expression was even more dramatic at 11 days after eclosion. Not a single gene was differentially expressed between haploid and diploid males, whereas 2257 and 2159 genes were differentially expressed between queens and diploid or haploid males, respectively. About 82% of all genes evidently are sex-specific in their expression at this age (figure 2).

The high similarity in transcriptional profiles between adult diploid and haploid males was also reflected in the clustering analysis. Diploid males invariably clustered with haploid males rather than with queens both at 1 day and at 11 days of age (figure 3; electronic supplementary material, figure S2).

Consistent with the high similarity in transcriptome profiles between diploid and haploid adult males, GO terms analysis revealed no overrepresentation of particular gene categories among genes differentially expressed between the two types of 1-day-old adult males (no genes were differentially expressed between the two types of older males; figures 1 and 2). Similarly, no GO category was overrepresented for genes upregulated in queens compared to the two types of males at either timepoint in the adult stage, although several categories involved in translation and metabolic activity were overrepresented among genes downregulated in queens (electronic supplementary material table S5).

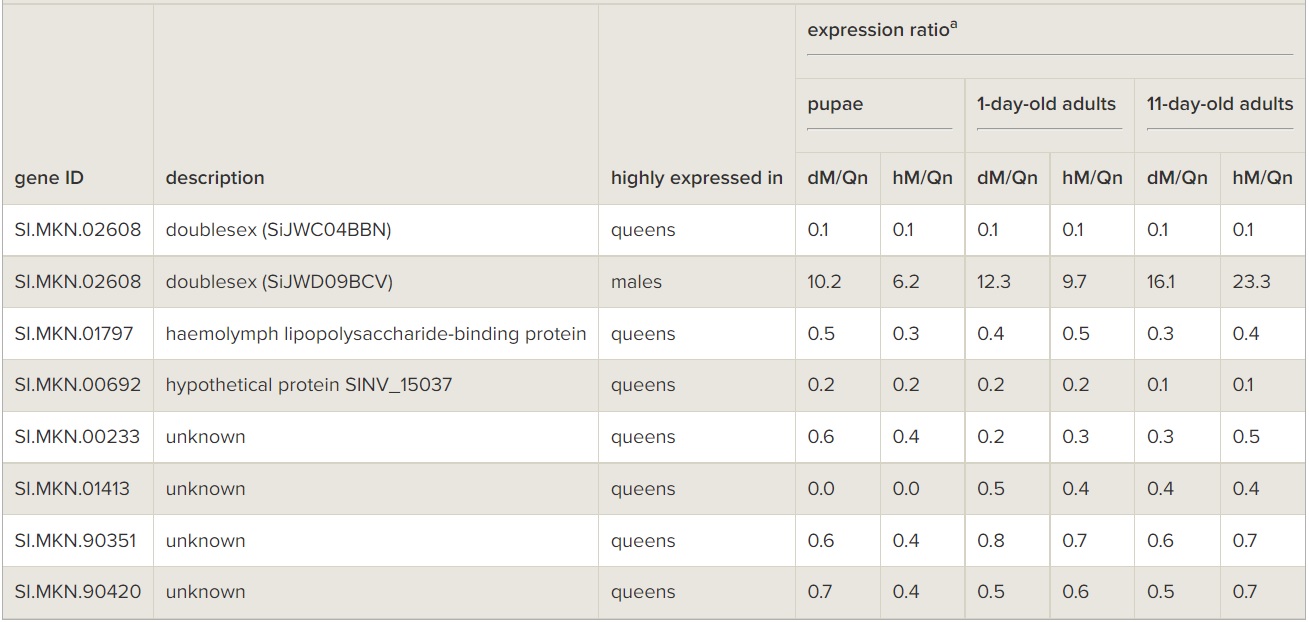

There were only seven genes (dsx, haemolymph lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, and five genes with unknown function) that exhibited sex-biased expression at all three timepoints (table 1). RNAseq data (O. Riba-Grognuz, J. Romiguier, Y. Wurm, M. Nipitwattanaphon, L. Keller, 2014, unpublished data) have shown that the fire ant dsx gene is alternatively spliced in a sex-specific manner by omitting the 5th exon from the pre-mRNA of males while omitting the 6th and 7th exons from that of females (electronic supplementary material, figure S3a and table S6). Consistent with this, our microarray data revealed that one of the two dsx cDNA spots (SiJWC04BBN), which corresponds to the 5th exon sequence, was always comparatively abundant in queens at all developmental timepoints (more than eightfold higher than in males), while the other spot (SiJWD09BCV), which corresponds to the 7th exon sequence, was always comparatively abundant in both diploid and haploid males at all timepoints (more than sixfold higher than in queens; table 1; electronic supplementary material, figure S4). Quantitative RT-PCR confirmed that expression of the 6th and 7th exons, as well as of the direct Exon 4-to-Exon 6 splice junction, was significantly higher in males than in queens at all developmental timepoints (electronic supplementary material, figure S3b-d, ANOVA, all p < 0.01), whereas the opposite pattern was found for the 5th exon (electronic supplementary material, figure S3e, ANOVA, p < 0.01). The 4th exon, which should be expressed in both sexes, was slightly more highly expressed in males than in queens (electronic supplementary material, figure S3f).

Table 1

Genes consistently differentially expressed between S. invicta males and queens at three developmental timepoints. dM, diploid male; hM, haploid male; Qn, queen.

aExpression ratio for the first category relative to the second category.

(c) Misexpression of genes implicated in sperm production and in pheromone production/perception in diploid male pupae

All 12 genes implicated in sperm production were differentially expressed between the three types of pupae (electronic supplementary material, figure S5 and table S7). The level of expression was higher in haploid males compared with both diploid males and queens. The pattern of expression of these genes was actually very similar between diploid males and queens, supporting the idea that their underexpression during the pupal stage may be responsible for the aspermic condition of diploid male fire ants.

To assess whether the failure of worker fire ants to eliminate diploid males might be due to these males being chemically indistinguishable from queens, we compared patterns of expression in pupae of genes probably involved in pheromone production/perception. Of the 154 such genes on our microarray, 66 (42.6%) were differentially expressed among the three types of pupae. Of these, 49 (74.2%) showed a consistent pattern of expression associated with just ploidy level (i.e. haploid males differed significantly from both queens and diploid males; electronic supplementary material, figure S6 and table S8), two were associated with both ploidy level and sex (i.e. each type of pupa differed from both other types) and none was associated with just sex. Misexpression in diploid male pupae of the 49 genes with ploidy-specific expression conceivably plays a role in workers’ inability to systematically discriminate against diploid males during their rearing, assuming these genes are involved in normal chemical signalling of brood sex.

4. Discussion

This study compared gene expression levels of diploid males, haploid males and queens of the fire ant S. invicta at three developmental timepoints in order to discern the relative importance of ploidy level and sex in determining transcription profiles. In a previous study, Ometto et al. [32] also compared gene expression between S. invicta males and queens at the pupal and adult stages. There was a good agreement between the two studies, with most of the gene differently expressed in Ometto et al. [32] being also differently expressed in this study (electronic supplementary material, figure S7). However, because Ometto et al. did not analyse diploid males and only considered adults at one timepoint, they were not able to disentangle the roles of ploidy level and sex on gene expression and development.

Our results revealed strong and consistent associations of both ploidy level and sex on patterns of gene expression. Most strikingly, there was a strong and unexpected shift in the relative contributions of these two factors between the pupal and adult stages. In the pupal stage, most of the observed differences in transcriptome profiles among the three categories of individuals were associated with ploidy level, whereas in adults, sex was the most important factor associated with gene expression levels.

The large number of genes differentially expressed according to ploidy level in pupae is somewhat surprising because studies in plants and yeast have found that expression levels of only relatively few genes are affected by ploidy level (approx. 10% of the potato genome [38], only 17 genes in yeast [39]). The large number of genes differentially expressed between haploid and diploid pupae in fire ants may be due in some measure to differences in the numbers and types of tissues assayed in haploids versus diploids [38]. We used whole bodies and thus simultaneously assayed many tissue types that may differ in their extent of development between individuals of different ploidy levels, thus magnifying any tissue-specific expression differences. Two recent studies [21,22] comparing whole-body haploid and diploid males in the stingless bee Melipona quadrifasciata identified fewer than 100 differentially expressed genes, but this low number may be due primarily to the small number of genes examined compared to our study. Although ploidy is associated with cell size in other organisms, such an association is not known in ants, except for sperm cells of Lasius sakagamii [16]. It is possible that the ploidy effects found in this study are associated with the level of endopolyploidization of internal organs, which is generally higher in haploid males than diploid individuals (reproductive females and workers) in ants [20] or with epigenetic effects [40,41] associated with dosage compensation of the genome [42]. The potential role of such effects in diploid males, especially in the larval and early pupal stages, is worthy of additional investigation in fire ants.

Four lines of evidence indicate that the apparent similarity in gene expression profiles between diploid males and queens early in the pupal stage was not due to mis-identification of either queens or diploid males or to mislabelling of either RNA or hybridization samples. First, fire ant male and queen pupae clearly are morphologically distinguishable. Second, the five source colonies for diploid males all produced large numbers of diploid males (more than 100) but no daughter queens, making it highly unlikely that any queens were among the 10 samples assigned as diploid males (assuming even a 1% rate of queen production and random sampling, the binomial probability of sampling more than one queen in 10 samples is less than 0.5%). Third, the microarray hybridization pattern at the spots corresponding to the male- and female-specific dsx splice forms matched the presumed sex for all 29 pupae (nine haploid males, 10 diploid males and 10 queens) as well as all adults analysed (electronic supplementary material figure S4). Finally, qRT-PCR testing of dsx expression on 36 of the original mRNA samples used in the microarray hybridizations (13 of which were pupae) revealed that the pattern of sex-specific alternative splicing for dsx always matched the presumed sexual identity of individuals (electronic supplementary material, figure S3).

Our finding that gene expression patterns in the pupal stage are more similar between diploid males and queens than between diploid and haploid males, while unexpected, may be at least partly explained as follows. The 1–2-day-old pupae that we sampled already have clearly distinguishable, sex-specific external morphologies, yet because the sex-specific differences in many common external features (e.g. heads and eyes) are only in degree (size and shape), they may arise as a result of rather limited changes in expression profiles among the large suite of genes surveyed in our whole-body assays. By contrast, internal organs, including those of the reproductive system, are still largely immature and undeveloped at this early timepoint. In addition, genes controlling differences between the sexes, e.g. dsx, are often only expressed in a few tissues (i.e. sex-specific cells), and thus the expression profiles of most tissues could be predominantly affected by ploidy rather than sex [43]. In ants, the testes develop and sperm are produced throughout the course of the pupal stage. Thus, part of the difference in gene expression between young haploid and diploid male pupae could reflect differences in the pattern or timing of sexual maturation between these two types. In this respect, it is important to note that diploid male fire ants almost invariably fail to develop testicular lobes [12] and are aspermic [14]. It is thus notable that all 12 genes identified as involved in sperm production were more highly expressed in haploid than diploid males, and that the patterns of low expression were similar between diploid male and queen pupae, both of which have undifferentiated and undeveloped gonads. Importantly, none of these 12 genes was still differentially expressed between the two types of males once the adults reached 11 days of age, probably reflecting the fact that the testes of haploid males have degenerated by this age [44]. Moreover, the presence of sperm in the vas deferens of haploid males [12] may have very limited effects on overall patterns of gene expression in the two types of males, because there seems to be minimal gene expression in sperm [45].

The close resemblance of diploid male expression patterns to those of queens early in the pupal stage is of further significance with respect to discrimination behaviour and the effects of loss of allelic variability at the CSD locus in invasive populations of S. invicta. Matings that give rise to diploid male offspring are far more common in the invasive than native populations owing to the loss of CSD alleles associated with founding of the USA populations [29]. In the monogyne (single-queen) social form, colonies initiated independently by queens that produce diploid males are doomed to failure because of the substantial investment in such males at an inappropriate phase of the colony cycle [24]. In the polygyne (multiple-queen) form in the invasive range, colonies invest heavily in such males throughout the favourable season, presumably at the expense of investment in fertile sexuals, with diploid males comprising 73–100% of the total number of males produced [29]. The enormous fitness costs in both forms of investing in these sterile males, which also do not contribute labour to the colony, is manifested because queens and workers evidently fail to recognize them and to terminate rearing early (as is done by worker honeybees [7]). The chemical signals produced by diploid male fire ant brood, via which worker discrimination among brood for termination or completion of rearing presumably is mediated, apparently are not sufficiently distinct from those of queens (or of workers) to provide a useful discrimination signal. In this respect, we note that almost 50 genes implicated in pheromone production/perception showed expression patterns associated only with ploidy level in the pupal stage, but not a single such gene showed an expression pattern associated only with sex. Thus, the similar expression of chemosensory-related genes in diploid male and queen pupae may translate to similar pheromonal profiles that restrain worker discrimination against such males.

Among the very few genes found to exhibit sex-biased expression differences in diploid pupae (38 genes, 0.6% of total genes on the array) is dsx (table 1). The orthologue of this gene in Drosophila mediates sexual differentiation by affecting both downstream genes that control sex-specific morphological differentiation [46] and other genes with sex-specific expression. Similar to honeybees [47], the fire ant dsx gene is alternatively spliced by omitting the 5th exon from the pre-mRNA of males while omitting the last two (6th and 7th) exons in females (electronic supplementary material, figure S3a). Importantly, the dsx mRNA including the 5th exon transcript is always more abundant in fire ant queens at all developmental timepoints, while the alternatively spliced mRNA with the 6th and 7th exon transcript is always more abundant in males (both diploid and haploid) at all developmental timepoints (electronic supplementary material, figure S3). This consistent difference between queens and males throughout development indicates the sensitivity of our microarrays for detecting sex-biased gene expression differences and, more importantly, supports the idea that the sex-differentiation role of dsx is conserved in insects as well as other animals [47].

Approximately 30% of the genes we surveyed in adults exhibited sex-biased expression, at both 1 day and 11 days of age. The fact that this proportion is somewhat lower than in Drosophila and Anopheles adults (more than 50%) [48,49] may be due to the fact that we extracted RNA from whole individuals, which results in reduced sensitivity for detecting sex-biased genes whose expression is limited to specific organs or structures (e.g. reproductive organs or the head [48]). We also found that genes differentially expressed between the sexes were equally likely to be over-expressed in either males or females. This contrasts with findings in Drosophila, where male-biased genes predominate [49], and in Anopheles gambiae, where female-biased genes predominate in terms of upregulation of expression [48].

Gene enrichment analysis showed that, among genes more highly expressed in males than in queens, those involved in metabolism and protein synthesis were overrepresented. Such results likely are indicative of a higher metabolic rate in males than in queens, which is consistent with the smaller size of fire ant males [8]. In addition, findings in Anopheles and bovine blastocysts suggest that mitochondrial gene expression and metabolic rates are elevated in males compared to females [50,51].

In conclusion, our results show that both ploidy and sex have important effects on gene expression patterns in fire ants but that these effects are developmental stage-specific. Ploidy has a strong effect on gene expression early in the pupal stage but a minimal effect by adulthood, whereas sex has only a small effect in the pupal stage but a very strong effect in adults. Complex interactions of these two factors, as well as their interaction with actual sex phenotype, are likely. For instance, while sex phenotype clearly results from differential expression profiles initiated by the CSD locus genotype, it also likely feeds back on and thus modulates the form of these profiles during ontogeny.

Data accessibility

Gene expression data meet MIAME standards and have been deposited at Gene Expression Omnibus (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE42786.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jezaelle Rufener, Laelia Maumary, Jérôme Notari and Sasitorn Hasin for ant care; Christine LaMendola for laboratory assistance; Céline Stoffel, Hannes Richter, Eyal Privman and Michiel B. Dijkstra for qPCR help; Markus Affolter, Daniel Bopp and two reviewers for useful comments: the staff of the DNA Array Facility of the University of Lausanne for microarray printing, advice, and access to software.

Funding statement

We thank the Royal Thai Government, the University of Lausanne and the Société Académique Vaud for financial support. This research was supported by TRG5780279, Academia Sinica, Taiwan MOST (#103-2311-B-001-018-MY3 and #103-2621-M-001-004), several grants from the Swiss NSF, and an ERC advanced grant.

Supplemental Material

-

rspb20141776supp2.pdf – [.PDF, 5.9 MB]

-

rspb20141776supp1.docx – [.DOCX, 160.0 KB]

-

rspb20141776supp3.xls – [.XLS, 2.0 MB]

-

rspb20141776supp4.txt – [.TXT, 17.9 MB]

References

-

Beukeboom LW& Perrin N. 2014 The evolution of sex determination. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

-

Bull JJ. 1983 Evolution of sex determining mechanisms. New York, NY: Benjamin.

-

Beye M, Hasselmann M, Fondrk MK, Page RE& Omholt SW. 2003 The gene csd is the primary signal for sexual development in the honeybee and encodes an SR-type protein. Cell 114, 419–429. (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00606-8).

-

Whiting P. 1943 Multiple alleles in complementary sex determination of habrobracon. Genetics 28, 365–382.

-

Cowan DP& Stahlhut JK. 2004 Functionally reproductive diploid and haploid males in an inbreeding hymenopteran with complementary sex determination. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10 374–10 379. (doi:10.1073/pnas.0402481101).

-

Bostian CH. 1935 Biparental males and hatchability of eggs in habrobracon. Genetics 20, 280–285.

-

Herrmann M, Trenzcek T, Fahrenhorst H& Engels W. 2005 Characters that differ between diploid and haploid honey bee (Apis mellifera) drones. Genet. Mol. Res. 4, 624–641. PubMed,

-

Ross KG& Fletcher DJC. 1985 Genetic origin of male diploidy in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), and its evolutionary significance. Evolution (N. Y). 39, 888–903. (doi:10.2307/2408688).

-

Van Wilgenburg E, Driessen G& Beukeboom LW. 2006 Single locus complementary sex determination in Hymenoptera: an ‘unintelligent’ design?Front. Zool. 3, 1. (doi:10.1186/1742-9994-3-1).

-

Tavares MG, Teixeira Irsigler AS& De Oliveira Campos LA. 2003 Testis length distinguishes haploid from diploid drones in Melipona quadrifasciata (Hymenoptera: Meliponinae). Apidologie 34, 449–455. (doi:10.1051/apido:2003045).

-

Woyke J. 1974 Genic balance, heterozygosity and inheritance of testis size in diploid drone honeybees. J. Apic. Res. 13, 77–85.

-

Hung ACF, Vinson SB& Summerlin JW. 1974 Male sterility in the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 67, 4.

-

Ayabe T, Hoshiba H& Ono M. 2004 Cytological evidence for triploid males and females in the bumblebee, Bombus terrestris. Chromosom. Res. 12, 215–223. (doi:10.1023/B:CHRO.0000021880.83639.4b).

-

Krieger MJB, Ross KG, Chang CWY& Keller L. 1999 Frequency and origin of triploidy in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Heredity (Edinb). 82, 142–150. (doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6884600).

-

De Boer JG, Ode PJ, Vet LEM, Whitfield JB& Heimpel GE. 2007 Diploid males sire triploid daughters and sons in the parasitoid wasp Cotesia vestalis. Heredity (Edinb). 99, 288–294. (doi:10.1038/sj.hdy.6800995).

-

Yamauchi K, Yoshida T, Ogawa T, Itoh S, Ogawa Y, Jimbo S& Imai HT. 2001 Spermatogenesis of diploid males in the formicine ant, Lasius sakagamii. Insectes Soc. 48, 28–32. (doi:10.1007/PL00001741).

-

Woyke J& Król-Paluch W. 1985 Changes in tissue polyploidization during development of worker, queen, haploid and diploid drone honeybees. J. Apic. Res. 24, 214–224.

-

Aron S, de Menten L, Van Bockstaele DR, Blank SM& Roisin Y. 2005 When hymenopteran males reinvented diploidy. Curr. Biol. 15, 824–827. (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.017).

-

Leeb M& Wutz A. 2013 Haploid genomes illustrate epigenetic constraints and gene dosage effects in mammals. Epigenetics Chromatin 6, 41. (doi:10.1186/1756-8935-6-41).

-

Scholes DR, Suarez AV& Paige KN. 2013 Can endopolyploidy explain body size variation within and between castes in ants?Ecol. Evol. 3, 2128–2137. (doi:10.1002/ece3.623).

-

Borges AA, Humann FC, Oliveira Campos LA, Tavares MG& Hartfelder K. 2011 Transcript levels of ten caste-related genes in adult diploid males of Melipona quadrifasciata (Hymenoptera, Apidae)—a comparison with haploid males, queens and workers. Genet. Mol. Biol. 34, 698–706. (doi:10.1590/S1415-47572011005000050).

-

Borges AA, Humann FC, Tavares MG, Campos LAO& Hartfelder K. 2012 Gene copy number and differential gene expression in haploid and diploid males of the stingless bee, Melipona quadrifasciata. Insectes Soc. 59, 587–598. (doi:10.1007/s00040-012-0259-1).

-

Ellegren H& Parsch J. 2007 The evolution of sex-biased genes and sex-biased gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 689–698. (doi:10.1038/nrg2167).

-

Ross KG& Fletcher DJC. 1986 Diploid male production: a significant colony mortality factor in the fire ant Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 19, 283–291. (doi:10.1007/BF00300643).

-

Passera L& Keller L. 1992 The period of sexual maturation and the age at mating in Iridomyrmex humilis, an ant with intranidal mating. J. Zool. 228, 141–153. (doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1992.tb04438.x).

-

Wang J, Jemielity S, Uva P, Wurm Y, Gräff J& Keller L. 2007 An annotated cDNA library and microarray for large-scale gene-expression studies in the ant Solenopsis invicta. Genome Biol. 8, R9. (doi:10.1186/gb-2007-8-1-r9).

-

Jouvenaz DP, Allen GE, Banks WA, Wojcik DP, Entomologist TF& Dec N. 1977 A survey for pathogens of fire ants, Solenopsis spp., in the Southeastern United States. Florida Entomol. 60, 275–279. (doi:10.2307/3493922).

-

Krieger MJB& Ross KG. 2002 Identification of a major gene regulating complex social behavior. Science 295, 328–332. (doi:10.1126/science.1065247).

-

Ross KG, Vargo EL, Keller L& Trager JC. 1993 Effect of a founder event on variation in the genetic sex-determining system of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Genetics 135, 843–854.

-

Wang J, Wurm Y, Nipitwattanaphon M, Riba-Grognuz O, Huang Y-C, Shoemaker D& Keller L. 2013 A Y-like social chromosome causes alternative colony organization in fire ants. Nature 493, 664–668. (doi:10.1038/nature11832).

-

Krieger MJB& Keller L. 1997 Polymorphism at dinucleotide microsatellite loci in fire ant Solenopsis invicta populations. Mol. Ecol. 6, 997–999. (doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.1997.00264.x).

-

Ometto L, Shoemaker D, Ross KG& Keller L. 2011 Evolution of gene expression in fire ants: the effects of developmental stage, caste, and species. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 1381–1392. (doi:10.1093/molbev/msq322).

-

R Development Core Team. 2010 R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

-

Saeed AI, et al.2006 TM4 microarray software suite. Methods Enzymol. 411, 134–193. (doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(06)11009-5).

-

Götz S, et al.2008 High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 3420–3435. (doi:10.1093/nar/gkn176).

-

Alexa A& Rahnenführer J. 2010 topGO: Enrichment analysis for Gene Ontology. Bioconductor Packag. version 2.6.0. See www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/.

-

Nipitwattanaphon M, Wang J, Dijkstra MB& Keller L. 2013 A simple genetic basis for complex social behaviour mediates widespread gene expression differences. Mol. Ecol. 22, 3797–3813. (doi:10.1111/mec.12346).

-

Stupar RM, et al.2007 Phenotypic and transcriptomic changes associated with potato autopolyploidization. Genetics 176, 2055–2067. (doi:10.1534/genetics.107.074286).

-

Galitski T, Saldanha AJ, Styles CA, Lander ES& Fink GR. 1999 Ploidy regulation of gene expression. Science 285, 251–254. (doi:10.1126/science.285.5425.251).

-

Wurm Y, et al.2011 The genome of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5679–5684. (doi:10.1073/pnas.1009690108).

-

Smith CR, Mutti NS, Jasper WC, Naidu A, Smith CD& Gadau J. 2012 Patterns of DNA methylation in development, division of labor and hybridization in an ant with genetic caste determination. PLoS ONE 7, e42433. (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042433).

-

Glastad KM, Hunt BG, Yi SV& Goodisman MAD. 2014 Epigenetic inheritance and genome regulation: is DNA methylation linked to ploidy in haplodiploid insects?Proc. R. Soc. B 281, 1–7. (doi:10.1098/rspb.2014.0411).

-

Tanaka K, Barmina O, Sanders LE, Arbeitman MN& Kopp A. 2011 Evolution of sex-specific traits through changes in HOX-dependent doublesex expression. PLoS Biol. 9, e1001131. (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001131).

-

Tschinkel WR. 2006 The fire ants. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

-

Fischer BE, Wasbrough E, Meadows LA, Randlet O, Dorus S, Karr TL& Russell S. 2012Conserved properties of Drosophila and human spermatozoal mRNA repertoires. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 2636–2644. (doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0153).

-

Keisman EL, Christiansen AE& Baker BS. 2001 The sex determination gene doublesex regulates the A/P organizer to direct sex-specific patterns of growth in the Drosophila genital imaginal disc. Dev. Cell 1, 215–225. (doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00027-2).

-

Cho S, Huang ZY& Zhang J. 2007 Sex-specific splicing of the honeybee doublesex gene reveals 300 million years of evolution at the bottom of the insect sex-determination pathway. Genetics 177, 1733–1741. (doi:10.1534/genetics.107.078980).

-

Baker DA, Nolan T, Fischer B, Pinder A, Crisanti A& Russell S. 2011 A comprehensive gene expression atlas of sex- and tissue-specificity in the malaria vector, Anopheles gambiae. BMC Genomics 12, 296. (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-296).

-

Ranz JM, Castillo-Davis CI, Meiklejohn CD& Hartl DL. 2003 Sex-dependent gene expression and evolution of the Drosophila transcriptome. Science 300, 1742–1745. (doi:10.1126/science.1085881).

-

Bermejo-Alvarez P, Rizos D, Rath D, Lonergan P& Gutierrez-Adan A. 2010 Sex determines the expression level of one third of the actively expressed genes in bovine blastocysts. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 3394–3399. (doi:10.1073/pnas.0913843107).

-

Hahn MW& Lanzaro GC. 2005 Female-biased gene expression in the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Curr. Biol. 15, R192–R193. (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.005).

Footnotes

© 2014 The Author(s) Published by the Royal Society. All rights reserved.